Bias alert here, Swamp Thing was the comic that got me into comics, and for a long time, kept me buying. Like a lot of kids, I got a big stack of hand-me-down comics at a young age, including Swamp Thing issues 9 and 10. They were unlike anything I had ever read anywhere else, and still have a special place in my heart. They had such an effect on me that the second volume of Swamp Thing, starting in 1982, was the first comic series I followed regularly. I stopped at issue #10, and then returned four years later with Swamp Thing 48. Swamp Thing and I have history.

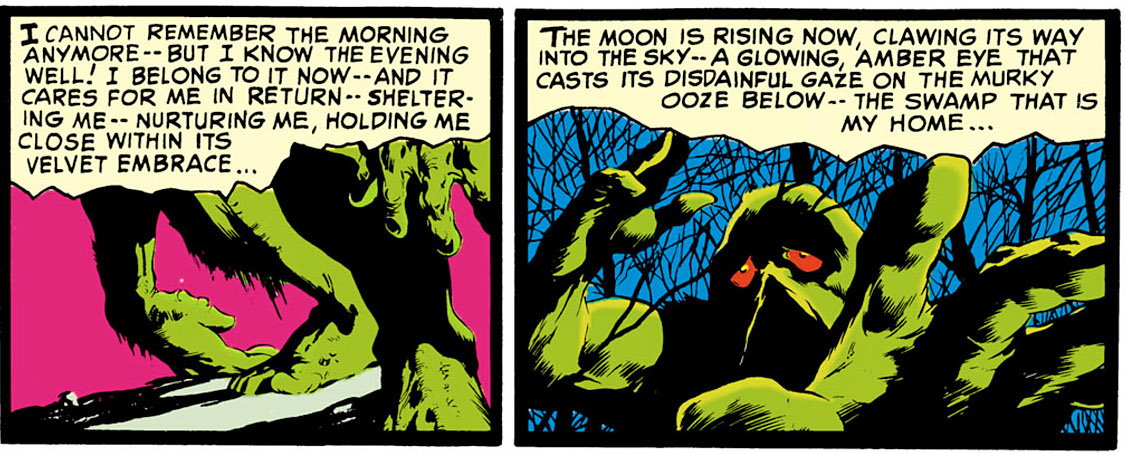

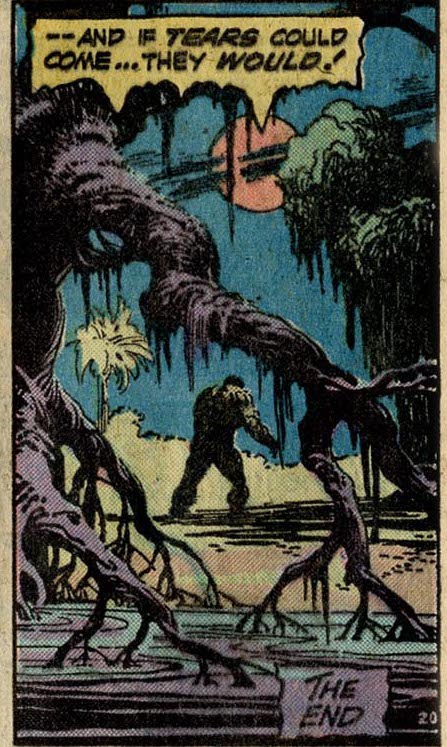

Swamp Thing’s initial story appeared in House of Secrets #92, cover date July, 1971, a collaboration between Len Wein and Bernie Wrightson. A one-shot Victorian Gothic tale of Alex Olsen, who is murdered and left to die in the swamp. He returns to find the murderer making the moves on his wife. Smashing through a window, he murders the man who murdered him. However, he cannot reconcile with his wife, she cannot recognize him in his new mucky form. He then returns to the swamp, forever. Len Wein’s wordsmithing in this story is excellent and moody, and Bernie Wrightson’s art is magnificent. What makes keeps it from being yet another "back from the dead to take revenge on the murderer" story is the heartfelt love story that underlies it. The images from the story, with the red eyes and the outstreteched hand, the image of the Swamp Thing peering at the house where it once had a normal life, have become iconic. From this story sprang so much of the non-superhero comics of the nineties and the first decade of the two thousands, two films, a cartoon, a live-action TV series, and more than four hundred stories featuring the character. Although the seminal partnership between Wein and Wrightson only lasted eleven stories, those classic stories have left an indelible mark on comics.

One year after House of Secrets 92, Wein and Wrightson brought the concept back, this time in a modern setting. They had been reluctant to do so, but were encouraged to do so by DC editor-in-chief Carmine Infanto, who had once been the illustrator for Hillman's Heap. As the new Swamp Thing (#1 cover date November 1972) this was an ongoing series, the background is better fleshed out, and Alec Holland is a more fully realized character than Alex Olsen was. And the Hollands are working on a biorestorative formula, a catalyst added to the swamp to make the transformation of the protagonist into a grotesque more credible. Interestingly, between the House of Secrets story and the first issue of Swamp Thing, Len Wein wrote the second Man-Thing story for Marvel. The story was shelved when Savage Tales #2 was postponed, but brought back by Roy Thomas, and saw print in Astonishing Tales, in June, 1972.

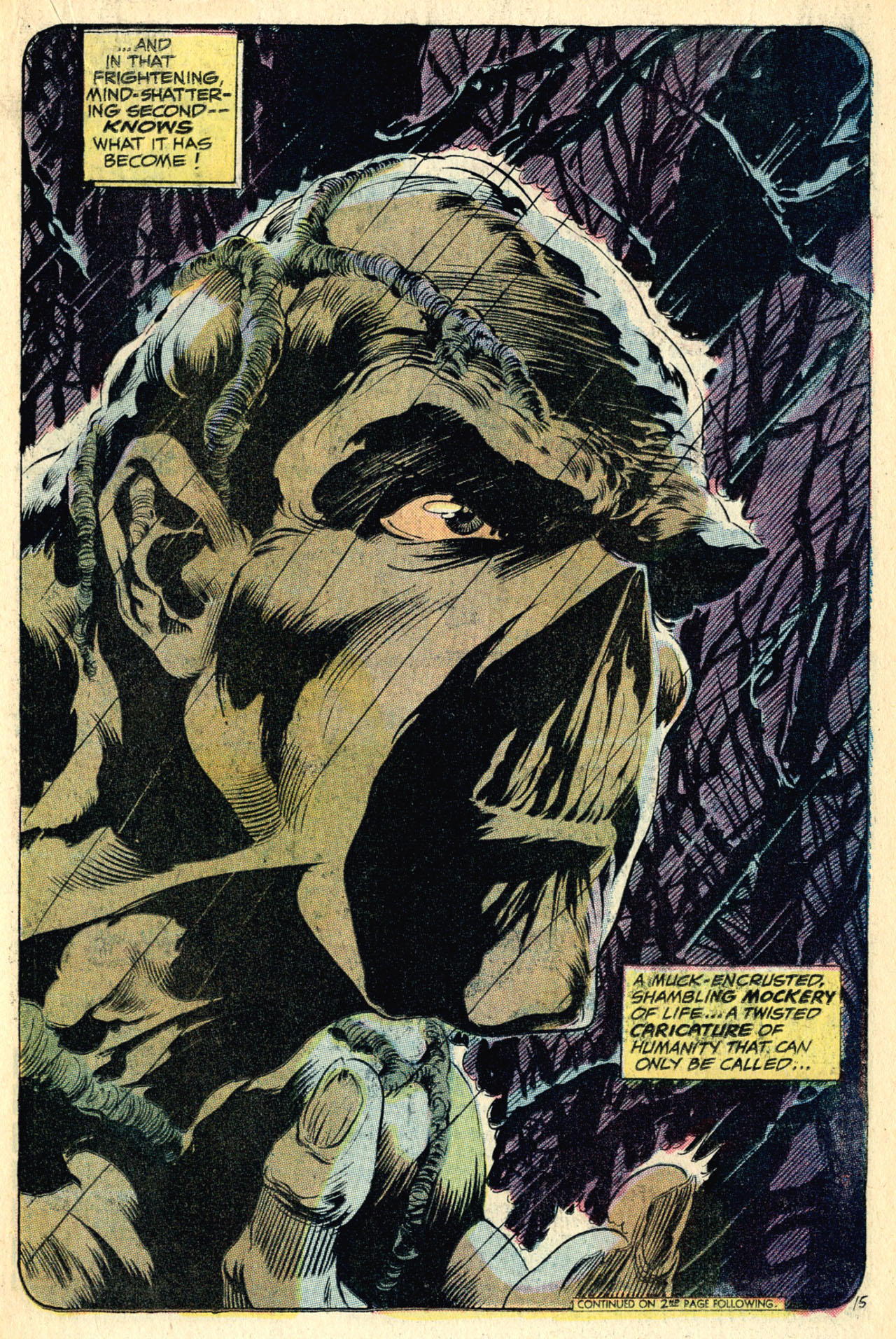

One year after House of Secrets 92, Wein and Wrightson brought the concept back, this time in a modern setting. They had been reluctant to do so, but were encouraged to do so by DC editor-in-chief Carmine Infanto, who had once been the illustrator for Hillman's Heap. As the new Swamp Thing (#1 cover date November 1972) this was an ongoing series, the background is better fleshed out, and Alec Holland is a more fully realized character than Alex Olsen was. And the Hollands are working on a biorestorative formula, a catalyst added to the swamp to make the transformation of the protagonist into a grotesque more credible. Interestingly, between the House of Secrets story and the first issue of Swamp Thing, Len Wein wrote the second Man-Thing story for Marvel. The story was shelved when Savage Tales #2 was postponed, but brought back by Roy Thomas, and saw print in Astonishing Tales, in June, 1972.As a character, the Swamp Thing is very different from the Hillman Heap, and Man-Thing. Not only does the creature retain the intellect of Dr. Alec Holland, it also retains some ability to speak. This also separates it from the Skywald Heap, which could think, but wasn’t a scientist, and couldn’t speak. As the decades have passed, speech has gotten easier for the Swamp Thing, but in the initial Wein and Wrightson stage, it’s pretty limited. Instead of being shaggy, as Man-Thing and the Hillman Heap are, the Swamp Thing is mossy, its surface (skin?) is smooth, although shot through with roots. It has the shape of a larger, more muscular man than Alec Holland was, as opposed to the shapeless goopiness of the Skywald Heap. Being able to reason and even sometimes speak allows the character a more active role in its stories. It need not be reactive, but can interpret what it sees without the need of an intermediary. Despite this, the Swamp Thing manages to get a supporting cast of humans, allowing for some complex stories told from different points of view.

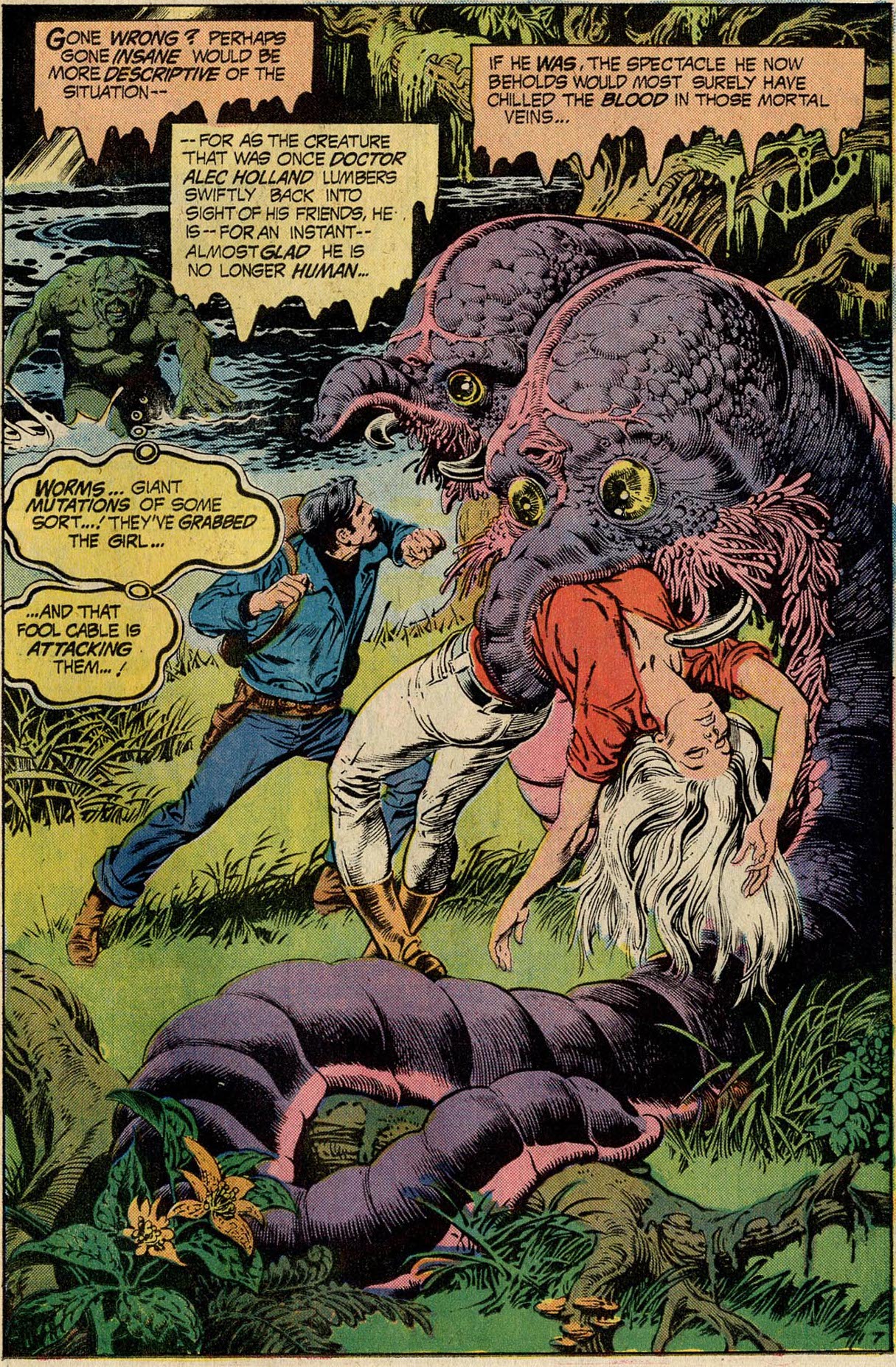

The Swamp Thing’s background cast is filled out with two people initially. Matt Cable was assigned to protect Alec Holland and now chases the Swamp Thing here and there across the globe. Cable is a bit generic, a down-on-his-luck government agent who hunts the monster that has ruined (in his opinion) his career. While on a trip to the Balkans, he picks up Abby Arcane, niece of recurring villain Anton Arcane. The two make a good team, although Abigail doesn’t have a lot of agency. They duo becomes a trio with Jefferson Bolt, a black man who was being held by the worms in issue eleven. Wein doesn't develop Bolt all that much, really only having two issues to do so. Bolt seems like he is there to provide conflict, or at least a different perspective that Abbey is unable to provide. The two (and then three) often provide a more human counterpoint to the Swamp Thing's stories, although occasionally (Issue 5 "Last of the Ravenwind Witches", and issue 10 "The Man Who Would Not Die") they don't show up at all. The supporting cast allowed Wein and Wrightson to approach stories from different perspectives. Issue 9, "The Stalker From Beyond" is an excellent example, switching perspective from Cable and the Abbey back to the Swamp Thing, moving the story forward through each character's perspective.

The Swamp Thing’s background cast is filled out with two people initially. Matt Cable was assigned to protect Alec Holland and now chases the Swamp Thing here and there across the globe. Cable is a bit generic, a down-on-his-luck government agent who hunts the monster that has ruined (in his opinion) his career. While on a trip to the Balkans, he picks up Abby Arcane, niece of recurring villain Anton Arcane. The two make a good team, although Abigail doesn’t have a lot of agency. They duo becomes a trio with Jefferson Bolt, a black man who was being held by the worms in issue eleven. Wein doesn't develop Bolt all that much, really only having two issues to do so. Bolt seems like he is there to provide conflict, or at least a different perspective that Abbey is unable to provide. The two (and then three) often provide a more human counterpoint to the Swamp Thing's stories, although occasionally (Issue 5 "Last of the Ravenwind Witches", and issue 10 "The Man Who Would Not Die") they don't show up at all. The supporting cast allowed Wein and Wrightson to approach stories from different perspectives. Issue 9, "The Stalker From Beyond" is an excellent example, switching perspective from Cable and the Abbey back to the Swamp Thing, moving the story forward through each character's perspective.

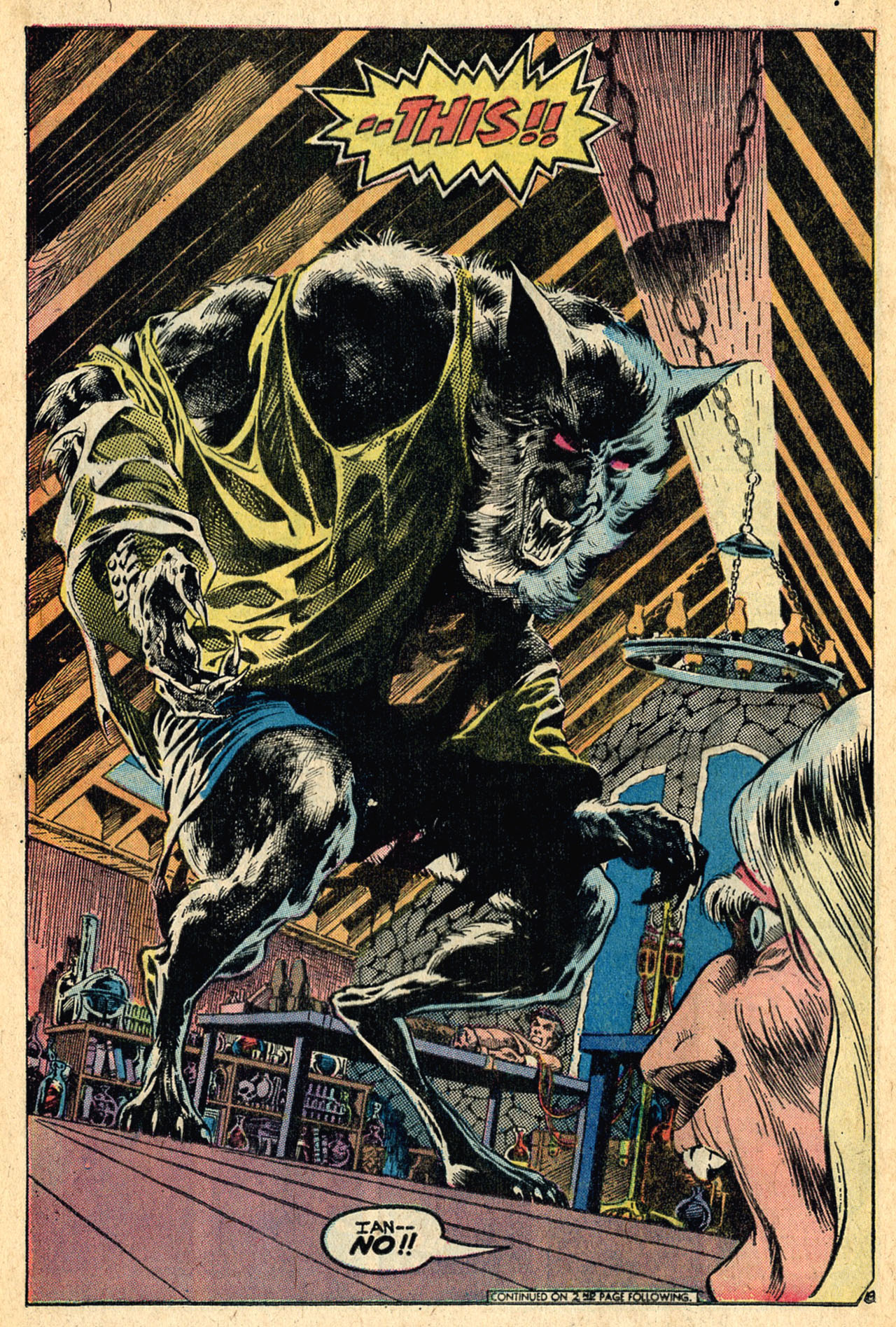

The initial story of Swamp Thing is strangely unlike like the rest of the book. It’s a modern revenge thriller, an expansion of the original story. Later stories are almost entirely Gothic. Sorcerers dreaming of immortality, werewolves, New England witches, creepy robot human replacements, a Lovecraftian horror down a mine shaft, and an alien all populate the pages. Only issues 1 “Dark Genesis” and 7 “Night of the Bat" are without supernatural of science-fiction trappings. Wein crammed a lot of story into the twenty-four pages, and while they are nods of homages to films like Freaks, The Wolf Man, and Frankenstein, they are not imitative. The werewolf story happens on the moors of Scotland, the alien story takes place in the swamps of Louisiana, giving each a unique setting and flavor. The book fell into a "monster of the week" format almost by default. Multi-issue story arcs were not the norm in the seventies, so this could be viewed as an extended horror anthology series, like House of Secrets, but sharing a protagonist. The stories often present a familiar trope, but they are always given a unique twist. And this is Wein's genius, and half the reason these stories have held up.

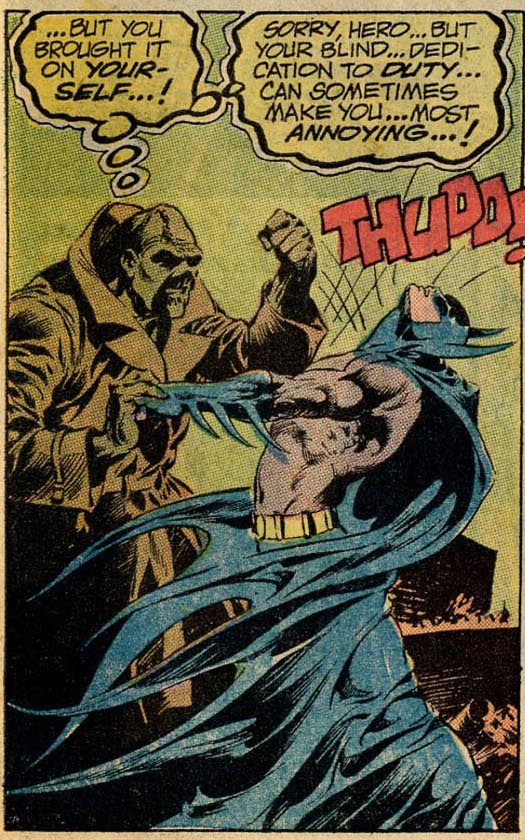

Swamp Thing interacts with the rest of the DC Universe only once during Wein and Wrightson’s time on the book. Swamp Thing comes to Gotham City, the home of Batman. The Batman concept is flexible enough that it doesn't break the Gothic horror atmosphere that Wein and Wrightson carefully cultivated. The story itself stretches the concept of the Swamp Thing himself. For the first time, he is in a city. And the plot is again not a horror one, but an investigation, but starring Batman and the Swamp Thing conducting parallel lines of inquiry, arriving at he same conclusion at the same time. It works as both a Batman mystery and a Swamp Thing horror story, and sets in motion an association between the Batman and Swamp Thing that would be fruitful for years to come.

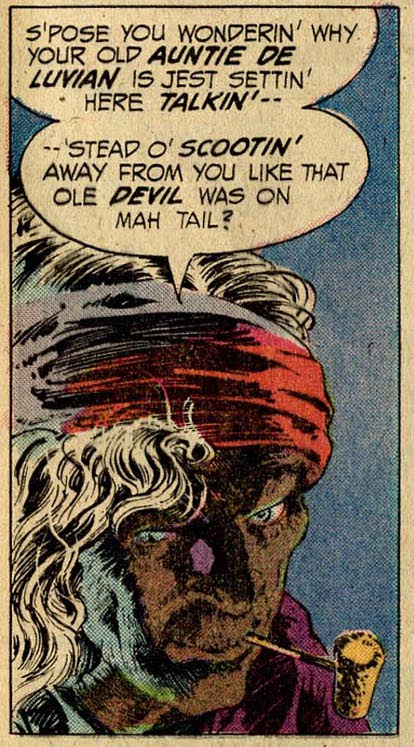

Issue 10 also deserves some special mention, since it’s the only issue with Wrightson as the plotter. It's a ghost story, as well as the return of Anton Arcane, who becomes the Swamp Thing's longest-lasting recurrine villain. His appearance here is quite memorable for its pure grotesqueness. Wrightson says the climax came from Ray Bradbury’s “The Handler” (adapted in Tales from the Crypt 36) and the parallel is easy to see. The image with the tombstones is very close to the Tales of the Crypt story. The story itself is radically different from the original Bradbury. It's a wonderfully dark story, and for once, the Swamp Thing is more a passive observer of the action rather than a participant. It’s a wonderfully dark story, very well told, and remains a personal favorite of mine. One point about "The Man Who Would Not Die" which I have never seen addressed, is the change of the old woman’s name from “Auntie De Luvian” to Auntie Bellum” in virtually every reprint I’ve seen. I’ve always wondered why tiny touch has been changed in the reprints.

Although I have written mostly about Wein's writing, I have to note that Wrightson's art is the perfect match to Wein's storytelling. He often adds strange or disconcerting angles to his art which makes it more powerful. He also ads subtle layers to stories that are not in Wein's scripts. For example, there is a sequence in "The Stalker From Beyond", a stack of page-wide panels in which the army squad is setting up camp. From the apparent chaos of the first panel, the men have resolved themselves into their respective sides concerning the fate of the alien. Those that want to kill it stand to the right, those that do not stand at the left. It’s a very subtle piece of art, but one that ads texture to the story. When Nestor Redondo took over the art chores with issue eleven, this layer of artistic nuance was lost. Which is not to say that Redondo was a bad artist. He isn't. He's an exceptional artist. But he was more of a superhero artist, so his choices of point of view tended to be more conventional.

Wein wrote another three issues with artist Nestor Redondo made the comic his, and gave us very strong art. Unfortunately, virtually anything would have seemed pale after the masterwork Wrightson did. That said, Redondo's art is sharp and very well defined, although not as detailed or chaiscuro as Wrightson. Len Wein’s stories remained solid, addressing more novel concepts such as alien worms that wanted to keep humanity for food stock, time travel, allowing some wonderful illustrations of strange worms, a Tyrannosaurus Rex, and lions from the Roman arena. But the stories were pitched and broken differently. They were were no longer a collaboration, but fully scripted by Wein before being sent to Redondo. So they have a different feel. They're still good, but they lack the sense of the Gothic and the grotesque that was present in first ten issues. The only thing I can say is that they feel more like a standard comic-book. A little more 'gonzo' and a bit less personal. They're still worth reading, but it seems clear that Wein was winding down his time on the book. As a lovely farewell, Wein ended the series with the same line that ended the short story: “... And if tears could come, they would.”

Wein wrote another three issues with artist Nestor Redondo made the comic his, and gave us very strong art. Unfortunately, virtually anything would have seemed pale after the masterwork Wrightson did. That said, Redondo's art is sharp and very well defined, although not as detailed or chaiscuro as Wrightson. Len Wein’s stories remained solid, addressing more novel concepts such as alien worms that wanted to keep humanity for food stock, time travel, allowing some wonderful illustrations of strange worms, a Tyrannosaurus Rex, and lions from the Roman arena. But the stories were pitched and broken differently. They were were no longer a collaboration, but fully scripted by Wein before being sent to Redondo. So they have a different feel. They're still good, but they lack the sense of the Gothic and the grotesque that was present in first ten issues. The only thing I can say is that they feel more like a standard comic-book. A little more 'gonzo' and a bit less personal. They're still worth reading, but it seems clear that Wein was winding down his time on the book. As a lovely farewell, Wein ended the series with the same line that ended the short story: “... And if tears could come, they would.”More than Man-Thing, which in its heyday was Steve Gerber's personal pulpit, the Wein and Wrightson Swamp Thing is foundational in the development of modern comics. Both of these comics sold well, outstripping popular superhero comics of their day. But Man-Thing doesn't seem to have acquired another writer who understood how to write compelling stories for the character, and Man-Thing has not managed to recapture its popularity under Gerber. Swamp Thing, on the other hand, managed to attract other authors and artists who would re-create the character, changing it from a simple "mucky human" into something larger and even more unique. Swamp Thing would eventually become the springboard from which DC Comics launched Vertigo, its successful line of horror comics in the early nineties. Swamp Thing is and remains a reminder that comics are not the exclusive domain of superheroes, that horror comics have and continue to be viable titles that, when well-written, sell well.

I hope I haven’t simply sung the praises of the Wein/Wrightson issues of Swamp Thing, but given the reader an idea of why I consider these to be some of the best comics ever produced. When it was going strong, Swamp Thing was one of DC Comics’ best sellers, and the stories have been endlessly reprinted. While the character has changed, especially after Alan Moore’s reinterpretation of the character in the eighties, these stories continue to be the firm foundation on which this extraordinarily popular character is based. The moody, beautiful art of Bernie Wrightson (and later, Nestor Redondo) combines with the carefully-chosen words of Len Wein to create a modern masterpiece, a book that i have read and re-read many times since I discovered it more than thirty-five years ago.