In 1979, Marvel decided that the Man-thing deserved to have its own book again. And so Man-Thing returned, resurrected by Michael Fleischer and later, Chris Claremont. This return lasted for eleven issues.

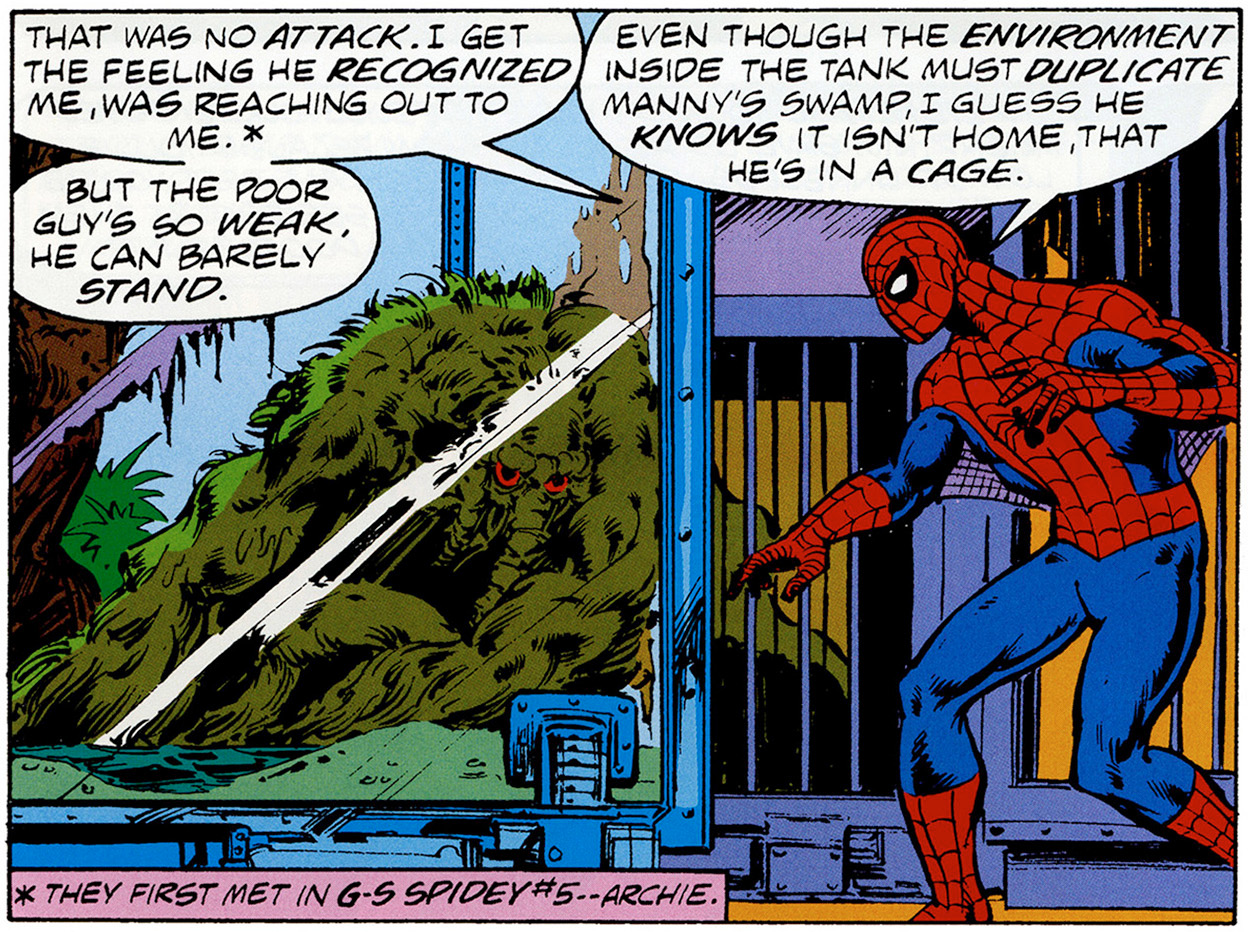

Neither Claremont not Fleischer were inexperienced writers. Claremont was in the process of writing his monumental X-Men run, one of the longest and most successful writing stints in comics history. Claremont started with a notable Man-Thing appearance in Marvel Team-Up #68, (April, 1978) introducing Man-Thing to Spider-Man, a pairing not as long-term fruitful as Man-Thing’s association with the Hulk, but a close second. This involves a very familiar prison, similar to the one Len Wein put the Swamp Thing in during the “Leviathan Conspiracy” (Swamp Thing # 13, Nov-Dec 1974). The captured swamp monster story hook is something that would be re-used when Swamp Thing was brought to Metropolis to meet Superman in DC Comics Presents # 8 “The Sixty Deaths Of Solomon Grundy” (April, 1979). Are our authors reading each others’ books? I think so. Claremont brings back Jennifer Kale and Dakimh the wizard from Gerber’s stint on the book. It’s a pretty standard superhero story. Dakimh and Jennifer are held hostage by costumes creep named D‘spayre. He can project burning fear on command, but Spider-man’s mental toughness allows him to eventually overcome it. It s a bit of a shock to read after the Gerber’s primarily narration-heavy stories. There’s a lot of supervillain monologing and Spider-man talking to himself to shake himself out of his fear. Man-Thing distracts D’spayre, and Spider-man is able to surprise him, and that’s about all of the story.

Neither Claremont not Fleischer were inexperienced writers. Claremont was in the process of writing his monumental X-Men run, one of the longest and most successful writing stints in comics history. Claremont started with a notable Man-Thing appearance in Marvel Team-Up #68, (April, 1978) introducing Man-Thing to Spider-Man, a pairing not as long-term fruitful as Man-Thing’s association with the Hulk, but a close second. This involves a very familiar prison, similar to the one Len Wein put the Swamp Thing in during the “Leviathan Conspiracy” (Swamp Thing # 13, Nov-Dec 1974). The captured swamp monster story hook is something that would be re-used when Swamp Thing was brought to Metropolis to meet Superman in DC Comics Presents # 8 “The Sixty Deaths Of Solomon Grundy” (April, 1979). Are our authors reading each others’ books? I think so. Claremont brings back Jennifer Kale and Dakimh the wizard from Gerber’s stint on the book. It’s a pretty standard superhero story. Dakimh and Jennifer are held hostage by costumes creep named D‘spayre. He can project burning fear on command, but Spider-man’s mental toughness allows him to eventually overcome it. It s a bit of a shock to read after the Gerber’s primarily narration-heavy stories. There’s a lot of supervillain monologing and Spider-man talking to himself to shake himself out of his fear. Man-Thing distracts D’spayre, and Spider-man is able to surprise him, and that’s about all of the story.More than a year later, Michael Fleischer wrote the first three comics in the new Man-Thing series, in 1979. Man-Thing’s tag line, “Whoever knows fear burns at the touch of the Man-Thing” is now on the cover.

CIA Deputy Director Smathers needs someone to reproduce Ted Sallis’s formula, to he abducts biochemist Dr. Cheimer and gives him a proposal. The CIA needs the supersoldier formula, before the Russians develop their own (always with the Russians, the CIA). Cheimar agrees, and the Man-Thing is trapped. Now, it should be said that at the beginning of the Marvel Team-up with Spider-man, Man-Thing was captured by carnival folk. Now, the government is going to build a hugely expensive trap. Cheimar is working on neural regeneration, and hopes that his work can make the Man-Thing sentient again. Of course, it’s not really the CIA, and SHIELD gets involved. They stage a raid, and Cheimar is killed in the ensuing action.

CIA Deputy Director Smathers needs someone to reproduce Ted Sallis’s formula, to he abducts biochemist Dr. Cheimer and gives him a proposal. The CIA needs the supersoldier formula, before the Russians develop their own (always with the Russians, the CIA). Cheimar agrees, and the Man-Thing is trapped. Now, it should be said that at the beginning of the Marvel Team-up with Spider-man, Man-Thing was captured by carnival folk. Now, the government is going to build a hugely expensive trap. Cheimar is working on neural regeneration, and hopes that his work can make the Man-Thing sentient again. Of course, it’s not really the CIA, and SHIELD gets involved. They stage a raid, and Cheimar is killed in the ensuing action. Next, the Man-Thing is teleported to the Himalayas, and is immediately beset by Himalayan wolves. And later a Himalayan brown bear. Each of these manages as well as do the gators back in Florida. Although out of its element, the Man-Thing manages to acquire some new companions, Russell and his wife Elaine, American mountain climbers in search of the Yeti. The Himalayas, are of course depicted as a series of snow-covered peaks. Where the wolves and the bear get their food, who knows. Muck monster versus bear bears some resemblance to Swamp Thing. There is a slight callback to Swamp Thing #8 (“The Lurker in Tunnel 13” Jan-Feb 1974) in which the Swamp Thing kills a bear in a cave during a snowstorm. The companions are then abducted by actual Yeti, who have accepted Hiram Swenson, an anthropologist, as their leader. After various shenanigans, the Man-Thing escapes the icy mountains by hanging onto the ski of a plane with one arm, and Elaine in the other.

Next, the Man-Thing is teleported to the Himalayas, and is immediately beset by Himalayan wolves. And later a Himalayan brown bear. Each of these manages as well as do the gators back in Florida. Although out of its element, the Man-Thing manages to acquire some new companions, Russell and his wife Elaine, American mountain climbers in search of the Yeti. The Himalayas, are of course depicted as a series of snow-covered peaks. Where the wolves and the bear get their food, who knows. Muck monster versus bear bears some resemblance to Swamp Thing. There is a slight callback to Swamp Thing #8 (“The Lurker in Tunnel 13” Jan-Feb 1974) in which the Swamp Thing kills a bear in a cave during a snowstorm. The companions are then abducted by actual Yeti, who have accepted Hiram Swenson, an anthropologist, as their leader. After various shenanigans, the Man-Thing escapes the icy mountains by hanging onto the ski of a plane with one arm, and Elaine in the other.Fleischer did not have the flair for the weird, or the personal, that Steve Gerber did. Man-Thing is not a book that is well-served by its supporting cast, but rather by the sort of stories that can be told about the wordless main character. Gerber’s endless reinvention of the genre of the book, and willingness to break the boundaries between superhero, fantasy, political satire, superheroes, and science fiction. Fleischer seems to be making this an adventure book, with exotic locations, daring escapes, helicopters, and explosions.

With issue four, the writer changed to Chris Claremont. Claremont, who was still writing X-Men at he time. He kicks off with a cross-over with Doctor Strange. Man-Thing and Elaine fall off the helicopter. Man-thing reappears in his swamp, mind-controlled by Baron Mordo. This all leads up to a large sorcerous working by Mordo. He has also kidnapped Jennifer Kale, although Dakimh is nowhere in evidence. Man-Thing and Dr. Strange work together to gum up the works, and succeed. Strange, in gratitude, attempts to turn Man-Thing back into Salis, but cannot. After all, if the Man-Thing became human again, where would the comic go? Better to tease the creature’s return to Ted Salis than to actually do it.

“Who Knows Fear,” issue #5 is a non-supernatural story, with Barbie, a young woman, being betrayed by a McGuire, a real bastard. He’s good-looking, setting up a simple dichotomy between the handsome man who is ugly on the inside, and the Man-Thing, ugly on the outside, but gentle and kind. The next story follows a similar plot, with a morally-bankrupt fraternity doing illegal things in order to capture the Man-Thing. Sheriff Daltry is caught in the middle of it. The plan is to make him the fear-generator that will attract the Man-Thing so the boys can spray him with defoliant. In the end, the good are rewarded, and the selfish frat boys who instigated the plan are dead. There’s more substance to the story: Claremont is a deeper writer than Flescher. He is developing a stronger supporting case, and the dichotomy between the attractive jerks and the good-but-ugly Man-Thing. Barb and Sheriff Daltry now for the new nucleus for the Man-Thing’s side characters. Barbie goes from being a fleeing victim to someone who is willing and able to fight back, which is a nice change.

“Who Knows Fear,” issue #5 is a non-supernatural story, with Barbie, a young woman, being betrayed by a McGuire, a real bastard. He’s good-looking, setting up a simple dichotomy between the handsome man who is ugly on the inside, and the Man-Thing, ugly on the outside, but gentle and kind. The next story follows a similar plot, with a morally-bankrupt fraternity doing illegal things in order to capture the Man-Thing. Sheriff Daltry is caught in the middle of it. The plan is to make him the fear-generator that will attract the Man-Thing so the boys can spray him with defoliant. In the end, the good are rewarded, and the selfish frat boys who instigated the plan are dead. There’s more substance to the story: Claremont is a deeper writer than Flescher. He is developing a stronger supporting case, and the dichotomy between the attractive jerks and the good-but-ugly Man-Thing. Barb and Sheriff Daltry now for the new nucleus for the Man-Thing’s side characters. Barbie goes from being a fleeing victim to someone who is willing and able to fight back, which is a nice change.The next two issues concern Captain Fate and his flying pirate ship. Claremont had clearly been reading Gerber’s work and wanted to expand on it. Fate is once again preying on jets, boarding them as if they were prize ships in the Caribbean. Fate imprisons Daltry and the Man-Thing together, which gives Daltry an opportunity to realize that the muck monster is not actively hostile, but can be approached by someone calm. It’s an important moment in their relationship. But Fate transfers the curse of immortality to Sheriff Daltry.

Issue nine was written by Dickie McKenzie. It’s an interesting variation on Wein’s “Sins of the Fathers” (Giant-Sized Man-Thing #5, as well as Gerber’s “Deathwatch” (Man-Thing #9). A couple run away to have their baby in the swamp, not having checked the water. They die, poisoned by a bad well, leaving the baby alive. Man-Thing receives the baby, and begins carrying it around the swamp. The baby’s gun-toting grandparents show up and attempt to take the baby, but whoever knows fear burns at the Man-Thing’s touch. Only one man is left, and the Man-Thing gives the babe to him. It's one of the very small, very personal stories and Gothic that Man-Thing can pull well, with the correct writer.

Issue nine was written by Dickie McKenzie. It’s an interesting variation on Wein’s “Sins of the Fathers” (Giant-Sized Man-Thing #5, as well as Gerber’s “Deathwatch” (Man-Thing #9). A couple run away to have their baby in the swamp, not having checked the water. They die, poisoned by a bad well, leaving the baby alive. Man-Thing receives the baby, and begins carrying it around the swamp. The baby’s gun-toting grandparents show up and attempt to take the baby, but whoever knows fear burns at the Man-Thing’s touch. Only one man is left, and the Man-Thing gives the babe to him. It's one of the very small, very personal stories and Gothic that Man-Thing can pull well, with the correct writer.There’s an additional story by JM DeMattis, who would later write Swamp Thing, Volume 3. The story develops as the experience of a high school student who was seduced by a cult, and then brutally deprogrammed. Having had several drug experiences, Larry doesn’t realize the Man-Thing isn’t a hallucination. Man-Thing shows up and the deprogrammers burn at his touch, and Tommy is reunited with his cult family. It’s a very ambiguous ending; the deprogrammers were brutes, but did they truly represent Tommy’s family’s wishes? The ending is melancholy, with the Man-Thing once again alone in the desert. I get the feeling this was cut down from a longer story: a lot happens in just five pages.

Claremont’s next issue “Swampfire” borrows a little bit from an early Heap story. John Kowalsi is a wandering veteran, who turns out to be the incarnation of Death. The cancellation of the book may have been immanent, and Claremont was clearing up the many loose ends. Barbie is transformed (one entire issue) into a death-dealing superhero.

Issue eleven was Claremont’s last, and he again imitates Gerber’s sign-off, as well as tying up as many of his series threads as possible. Claremont himself is a character, and he walks into Dr. Strange’s sanctum sanctorum, and gets drawn into the book itself. There’s a lot of fighting and revisiting of old characters, including Thog the Nether-Spawn. Ultimately, it feels like the issue is Gerber’s run put through a blender. I nthe end, Death and Dr. Strange reverse everything that has been done in the issue, and Daikh the Enchanter breaks the fourth wall and says farewell to the reader. It’s a a very unsatisfying end to the series, partially because, despite putting his own spin on the story, Claremont is retreading Gerber’s much more original idea.

Issue eleven was Claremont’s last, and he again imitates Gerber’s sign-off, as well as tying up as many of his series threads as possible. Claremont himself is a character, and he walks into Dr. Strange’s sanctum sanctorum, and gets drawn into the book itself. There’s a lot of fighting and revisiting of old characters, including Thog the Nether-Spawn. Ultimately, it feels like the issue is Gerber’s run put through a blender. I nthe end, Death and Dr. Strange reverse everything that has been done in the issue, and Daikh the Enchanter breaks the fourth wall and says farewell to the reader. It’s a a very unsatisfying end to the series, partially because, despite putting his own spin on the story, Claremont is retreading Gerber’s much more original idea.I suspect that Claremont could have gotten the hang of Man-Thing if he’d had more time on the book. But I expect that he was brought in when Michael Fleischer’s reboot of the book failed to take off. More themes could have been developed, Claremont could have broken free from Gerber’s characters and struck out on his own. But the character just wasn’t enough of a draw for readers to wait until the writer got the feel of the book.

It’s not a brilliant run, and clearly, Claremont and Fleischer lacked the feel for the Gothic combined with the very personal nature of Gerber’s work, which is what made it so popular. Man-Thing is not a superhero and cannot be treated as such. Weird adventures work better, and as McKenzie demonstrated with his fill-in story, non-supernatural stories work as well. But the Man-Thing is and remains a passive character, and cannot drive stories. Nor should it be used as a plot solver, in which it shows up at the end of a story and administers justice until the guilty parties have been beaten senseless. It’s a delicate balancing act, one that no one, aside from Gerber, has truly mastered in the long run. I want to so dome analysis of what was going on, but the run is so short, the stories so scattered that there's very little for me to sink my teeth into. I can say that Claremont likely read old Heap comics, and definitely Gerber's work, but seemed to have difficulty latching onto his own way of making Man-Thing stories.

And it’s a pity. Well-written Man-Thing stories are a pleasure to read. The character’s strange powers and swamp appearance tickle a very specific niche. I think it’s possible that, if given more time to develop themes and ideas, Claremont could have been a good writer of the series, made his mark on the on-going character. Unfortunately, Gerber started the character off on an extremely high note, and no one has yet returned with a clear, strong vision on how to make the character relevant or unique, the way Martin Pasko and Alan Moore did with the Swamp Thing.

Next time, we’re looking at the often-overshadowed Pasko Swamp Thing. It’s better than most people remember.

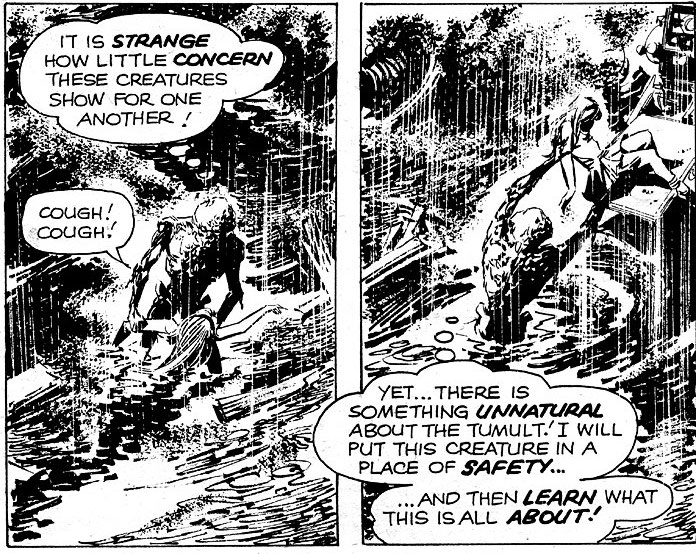

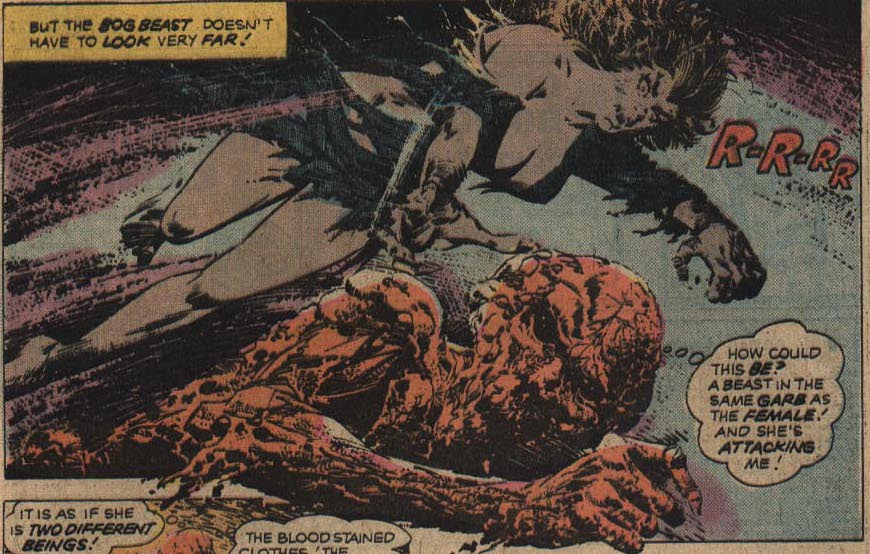

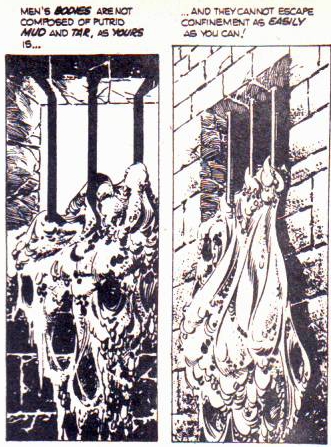

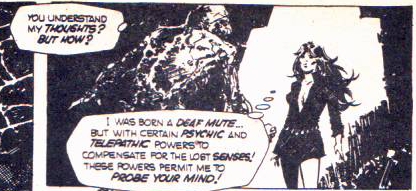

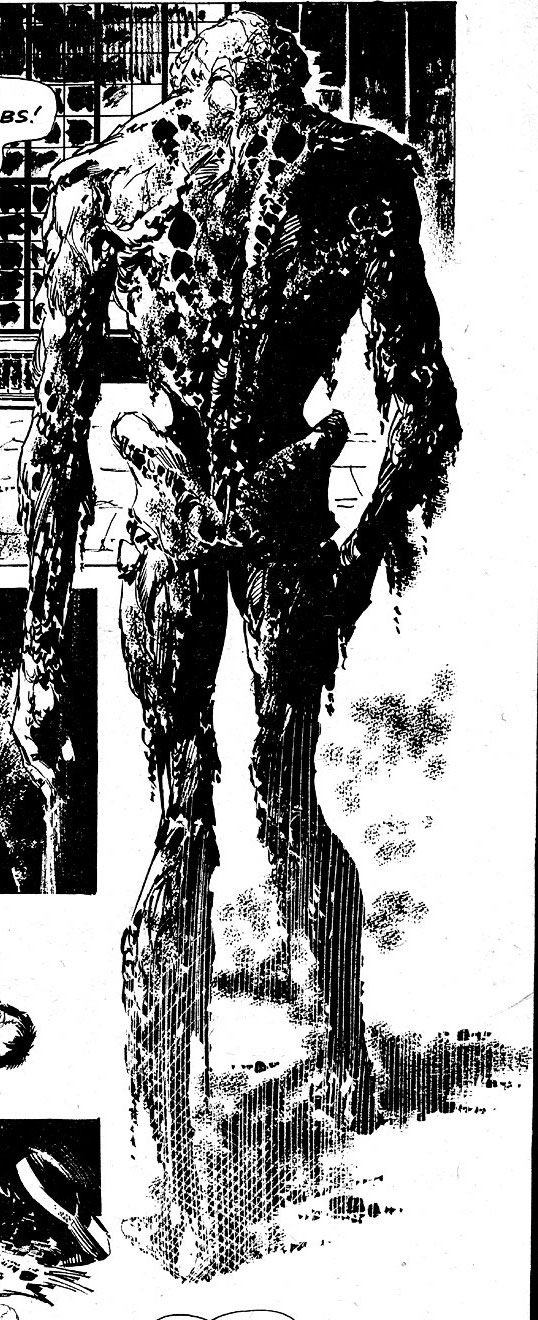

The 1974 version of Atlas Comics (from Seaboard Publishing) was another attempt to compete with Marvel and DC that did not last long. No comic or magazine they put out lasted more than four issues. As there was apparently some sort of mandatory swamp monster requirement for every seventies comic publisher, they introduced their own. Meet the Bog Beast.

The 1974 version of Atlas Comics (from Seaboard Publishing) was another attempt to compete with Marvel and DC that did not last long. No comic or magazine they put out lasted more than four issues. As there was apparently some sort of mandatory swamp monster requirement for every seventies comic publisher, they introduced their own. Meet the Bog Beast.