Swamp Thing hadn’t completely disappeared from the DC universe, but he was scarce enough to be legendary. As mentioned in the previous Swamp Thing entry, he guest starred in Challengers of the Unknown, written by Gerry Conway, the writer of the first Man-Thing story. This was followed by an appearance in The Brave and the Bold 122 (October 1975) when he again teamed up with Batman to defeat a super plant that threatened to take over Gotham. Alan Moore would use a similar plot, only with Swamp Thing as Batman’s antagonist instigating the plant growth. In DC Comics Presents #8, (April,1979) the Swamp Thing assisted Superman in defeating some sixty Solomon Grundies in a more superhero than horror story Steve Englehardt. Compared to Man-Thing, or any second-tier superhero, four years without an appearance is virtual character death.

I have, perhaps arbitrarily decided to mark the beginning of Swamp Thing volume 2 with The Brave and the Bold issue 176, from July 1981. It’s written by Martin Pasko, who would, one year later, take on the recrudescence of the Swamp Thing in May 1982. Before this story, Swamp Thing hadn’t been seen for two years.

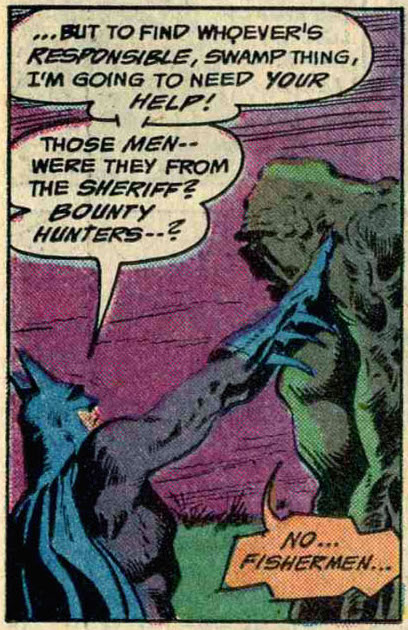

Pasko’s “The Delta Connection” is a straightforward Batman story from the early eighties; more Darknight Detective than Batgod, involving no other superpowered individuals. A man is murdered, and the search for the culprit takes Batman into the swamps of Louisiana. The Swamp Thing is coincidentally present, and a random shotgun blast allows the two to meet. Again. More likely to attract a Batman fan than a Swamp Thing fan, the story includes a one-page recapitulation of the Swamp Thing’s origin, and Pasko references their two previous encounters. In keeping with the Gothic atmosphere, and the resurgence of the weird in the eighties, Swamp Thing is given a vital but mysterious clue by a ghost. Later, the Swamp Thing concocts a rational explanation for this, but there’s definitely room to believe either way. Which is the strength of Pasko’s writing. The two solve the mystery and the criminals are brought to justice. It’s an atmospheric mystery, everything wrapped up. Pasko’s writing sets an excellent mood for the piece, and legendary Batman artist Jim Aparo artist does an excellent job with the swampy setting so distant from Gotham’s concrete jungles.

Pasko’s “The Delta Connection” is a straightforward Batman story from the early eighties; more Darknight Detective than Batgod, involving no other superpowered individuals. A man is murdered, and the search for the culprit takes Batman into the swamps of Louisiana. The Swamp Thing is coincidentally present, and a random shotgun blast allows the two to meet. Again. More likely to attract a Batman fan than a Swamp Thing fan, the story includes a one-page recapitulation of the Swamp Thing’s origin, and Pasko references their two previous encounters. In keeping with the Gothic atmosphere, and the resurgence of the weird in the eighties, Swamp Thing is given a vital but mysterious clue by a ghost. Later, the Swamp Thing concocts a rational explanation for this, but there’s definitely room to believe either way. Which is the strength of Pasko’s writing. The two solve the mystery and the criminals are brought to justice. It’s an atmospheric mystery, everything wrapped up. Pasko’s writing sets an excellent mood for the piece, and legendary Batman artist Jim Aparo artist does an excellent job with the swampy setting so distant from Gotham’s concrete jungles.I don’t know if Pasko was handed the Swamp Thing assignment because of this story, but it’s more than a coincidence that he was chosen to write the new Swamp Thing book.

The paradigm shifted slightly when Swamp Thing got its own series again. Pasko’s ideas were now very divorced from the mainstream DC Universe. No superheroes, not even Batman appear during his tenure. Only the Phantom Stranger, a mystical hero, appears, and those two stories are fill-ins written by Dan Mishkin. But there was a good reason for not including superheroes. Pasko set out to not write a kids’ book. His tenure on Swamp Thing deals with some very heavy psychological issues and current events, in the more or less direct way that Steve Gerber did in Man-Thing. This for-mature-readers approach was one of the stepping stones that eventually led DC to ditch the Comics Code Authority. Pasko deals with demons, child murder, Nazis, fanaticism, Vietnam, the aftereffects of electroconvulsive therapy, shady governmental-corporate partnerships, and the coming of the antichrist. It’s a heavy for a comic, especially one from the early eighties.

Len Wein was chosen as the editor. It must have been a strange sensation, editing another writer’s take on a character he had created. Even stranger to see Pakso update the character from Wein’s classic Gothic stories to neo-noir.

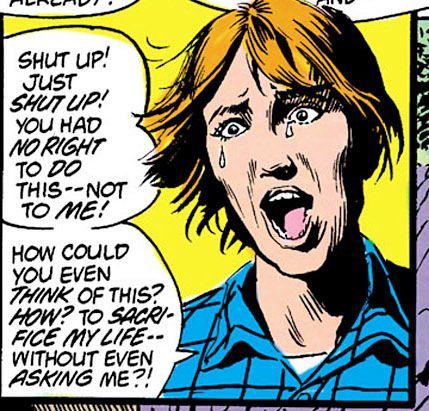

In the first issue, Swamp Thing rescues a mute girl in an act of kindness. Although young, she later proves to be anything but innocent. Her character arc is a beautiful inversion of the usual rescue of a child. What harm could come from saving a young girl, Karen Clancy from a father who is about to shoot her because he thinks she is some sort of witch spawn? It’s a familiar story, two outcasts bonding with each other. Pakso slowly transforms that initial rescue into a fantastic inversion of the story the readers expected. The issue also introduces “Harry Kay” an agent for the Sunderland Corporation. Kay turns out to have a lot of layers. Nobody is wholly good in Pasko’s Swamp Thing. And nobody is completely devoid of sympathetic qualities, either.

In the first issue, Swamp Thing rescues a mute girl in an act of kindness. Although young, she later proves to be anything but innocent. Her character arc is a beautiful inversion of the usual rescue of a child. What harm could come from saving a young girl, Karen Clancy from a father who is about to shoot her because he thinks she is some sort of witch spawn? It’s a familiar story, two outcasts bonding with each other. Pakso slowly transforms that initial rescue into a fantastic inversion of the story the readers expected. The issue also introduces “Harry Kay” an agent for the Sunderland Corporation. Kay turns out to have a lot of layers. Nobody is wholly good in Pasko’s Swamp Thing. And nobody is completely devoid of sympathetic qualities, either.In the very next issue the Swamp Thing and Karen are separated. They will never manage to truly get together again until the last two issues of the story arc, allowing for a diversity of stories as each character can be the protagonist on their own. When these other characters are the focus of a story, the Swamp Thing often plays the role the Heap did in the Hillman comics: arriving at the end to resolve the story. Pasko is too savvy to have the Swamp Thing administer justice, because there is no justice in these stories. The status quo is too flawed for anyone to desire a return to it.

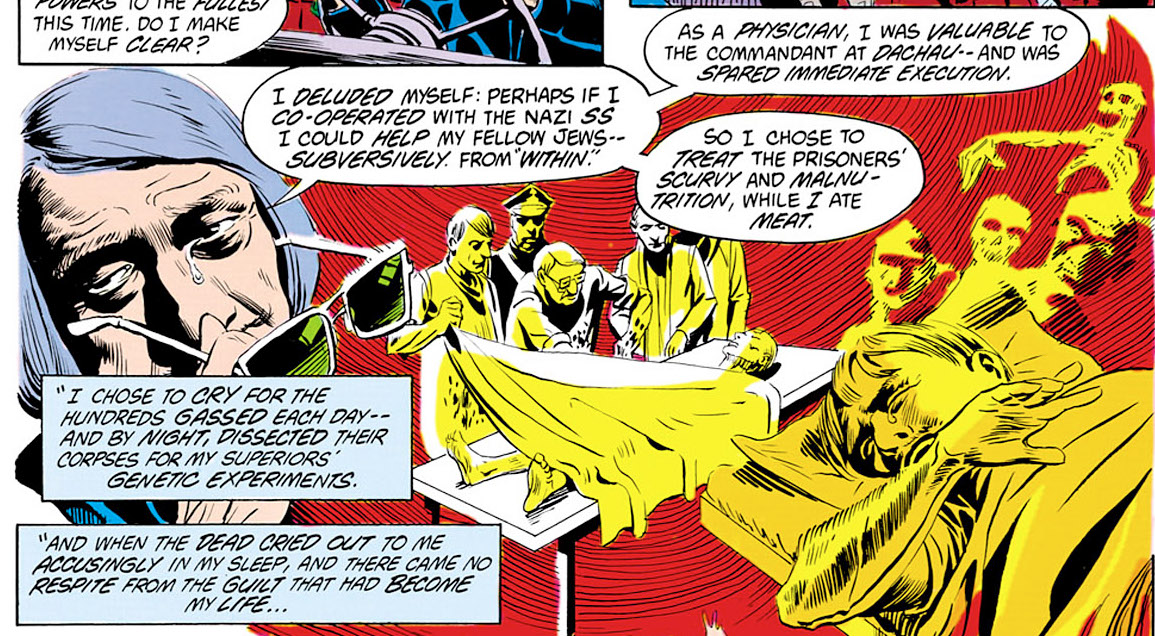

Other characters, often initially antagonistic to Swamp Thing or at odds with the rest of the cast, filter in. Liz Tremayne appears, a tough, no-nonsense reporter fighting for recognition as well as justice in the stories she reports. Helmut “Harry Kay” Kripptmann, a Jewish doctor and former Nazi collaborator, is morally ambiguous. Dr. Barclay starts as a naive “psychic” healer who doesn’t know he is the conduit transferring wounds from people onto captive clones. They are not heroes, but rather people with checkered pasts, attempting do to what is right by what they know. The frisson between the well-rounded characters makes the stories complex and interesting, and slowly layer after layer of the onion peels away until each character is exposed in all their complexity.

Other characters, often initially antagonistic to Swamp Thing or at odds with the rest of the cast, filter in. Liz Tremayne appears, a tough, no-nonsense reporter fighting for recognition as well as justice in the stories she reports. Helmut “Harry Kay” Kripptmann, a Jewish doctor and former Nazi collaborator, is morally ambiguous. Dr. Barclay starts as a naive “psychic” healer who doesn’t know he is the conduit transferring wounds from people onto captive clones. They are not heroes, but rather people with checkered pasts, attempting do to what is right by what they know. The frisson between the well-rounded characters makes the stories complex and interesting, and slowly layer after layer of the onion peels away until each character is exposed in all their complexity.

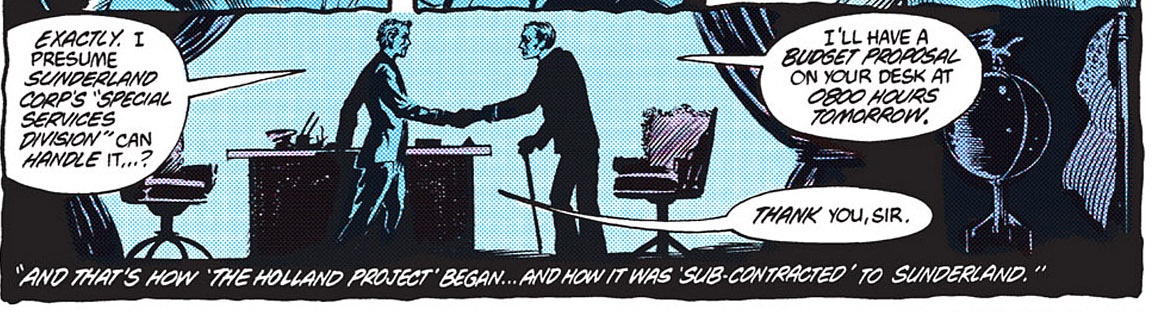

In the background looms Sunderland Corporation. Sunderland would be a standard evil corporation, similar to OCP, Weyland-Utani, Umbrella Corporation, or Abstergo, but these stories were written before any of these other companies were invented. Sunderland is always a shadowy presence with its filthy fingers in a large number of very dirty pies. In the Reagan/Thatcher area, Pasko also made sure that he reader knew that Sunderland had government ties, allowing it access to information and material it might not otherwise. The revelation that many large companies had government contacts was a shock to us in the eighties. It is understood to be a matter of course now.

In the background looms Sunderland Corporation. Sunderland would be a standard evil corporation, similar to OCP, Weyland-Utani, Umbrella Corporation, or Abstergo, but these stories were written before any of these other companies were invented. Sunderland is always a shadowy presence with its filthy fingers in a large number of very dirty pies. In the Reagan/Thatcher area, Pasko also made sure that he reader knew that Sunderland had government ties, allowing it access to information and material it might not otherwise. The revelation that many large companies had government contacts was a shock to us in the eighties. It is understood to be a matter of course now. Issue three introduces us to Rosewood, Illinois. The town has been taken over by vampires, and only a desperate family is left to resist them. But those who fight evil are not necessarily good people. Larry Childress blows up a local dam to flood the town, dissolving the vampires under running water. But he does so taking his son with him, where he could have left the boy out of harm’s way. His nihilism is not praised.

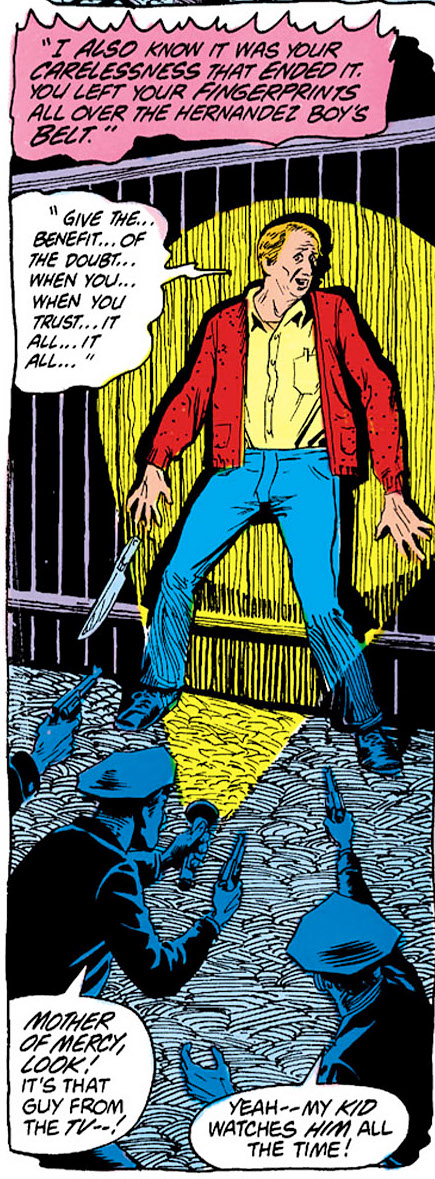

Issue three introduces us to Rosewood, Illinois. The town has been taken over by vampires, and only a desperate family is left to resist them. But those who fight evil are not necessarily good people. Larry Childress blows up a local dam to flood the town, dissolving the vampires under running water. But he does so taking his son with him, where he could have left the boy out of harm’s way. His nihilism is not praised. Issue four, “In the White Room” presents us with another complex situation. “Uncle Barney” a local kids TV show host, has been caught murdering children. His show’s catchy song “Give the benefit of the doubt/When you trust it all works out” is implied to have contributed to the murders, since kids trust Uncle Barney. That said, Barney made a pact with demons, which brought out his murderous desires. The demon escapes Barney and finds other hosts, Liz Tremayne is caught in the middle of the supernatural struggle. And though the demon is defeated, by the end of the issue, Uncle Barney has been replaced with “Aunt Polly” who has the same catchy tune about trust. Pineboro hasn’t learned anything.

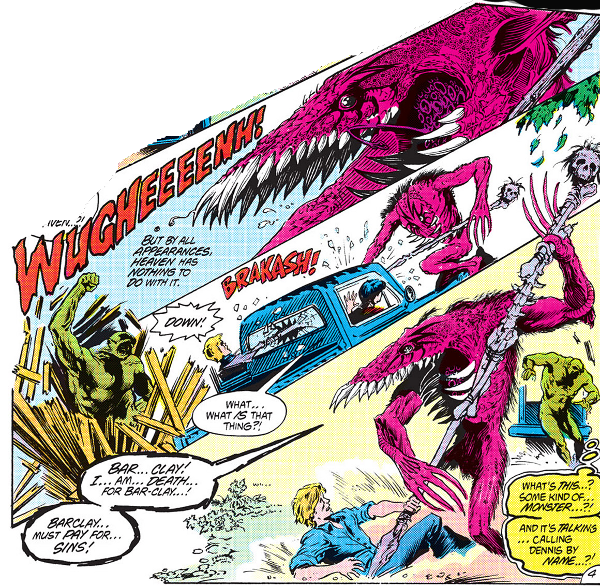

Issue four, “In the White Room” presents us with another complex situation. “Uncle Barney” a local kids TV show host, has been caught murdering children. His show’s catchy song “Give the benefit of the doubt/When you trust it all works out” is implied to have contributed to the murders, since kids trust Uncle Barney. That said, Barney made a pact with demons, which brought out his murderous desires. The demon escapes Barney and finds other hosts, Liz Tremayne is caught in the middle of the supernatural struggle. And though the demon is defeated, by the end of the issue, Uncle Barney has been replaced with “Aunt Polly” who has the same catchy tune about trust. Pineboro hasn’t learned anything.Issue Five “The Screams of Hungry Flesh” brings us Dennis Barclay, a doctor who is part of Sunderland. He’s a naive psychic healer working with Kripptmann. He discovers that he’s just transferring wounds onto semiconscious clones. Once the truth is revealed, he flees Sunderland and his clinic, adding another character to the Swamp Thing and Liz Tremayne party.

The next story, a two parter “Sins on the Water” and “I Have Seen the Splintered Timbers of a Hundred Shattered Hulls” is the most bizarre and comic-book story yet, starting with an alien invasion on a Sunderland corporate cruise, and ending up with isolated psychically-enhanced Vietnam vets who can alter reality. At its heart, “Here’s Looking at You, Kid” has a back and forth discussion about the treatment of those veterans. Pasko is canny enough not to let the story take sides. In the background, Casey is seen to be more dangerous, and Kripptmann is unable to apprehend her.

With issue nine, "Prelude to Holocaust", the series now shifts full-time to the Karen Clancy story. I suppose there’s a little bit of Stephen King’s Carrie in the little psychic girl, but Karen isn’t an innocent cursed with psychic abilities she can’t control. The little girl the Swamp Thing saved is the herald of the Antichrist. She’s an evil person, growing and developing her psychic powers, using them get what she wants. And to make sure we know she’s evil, Pasko shows her looting a Nazi collector’s stash for a particular item. Kripptmann is shown to have a larger agenda, using what resources he can glean from Sunderland to pursue Karen. And he is ruthless, even murdering Sunderland employees to get what he needs. He is not a good person, even though he stands opposed to both Sunderland and Clancy.

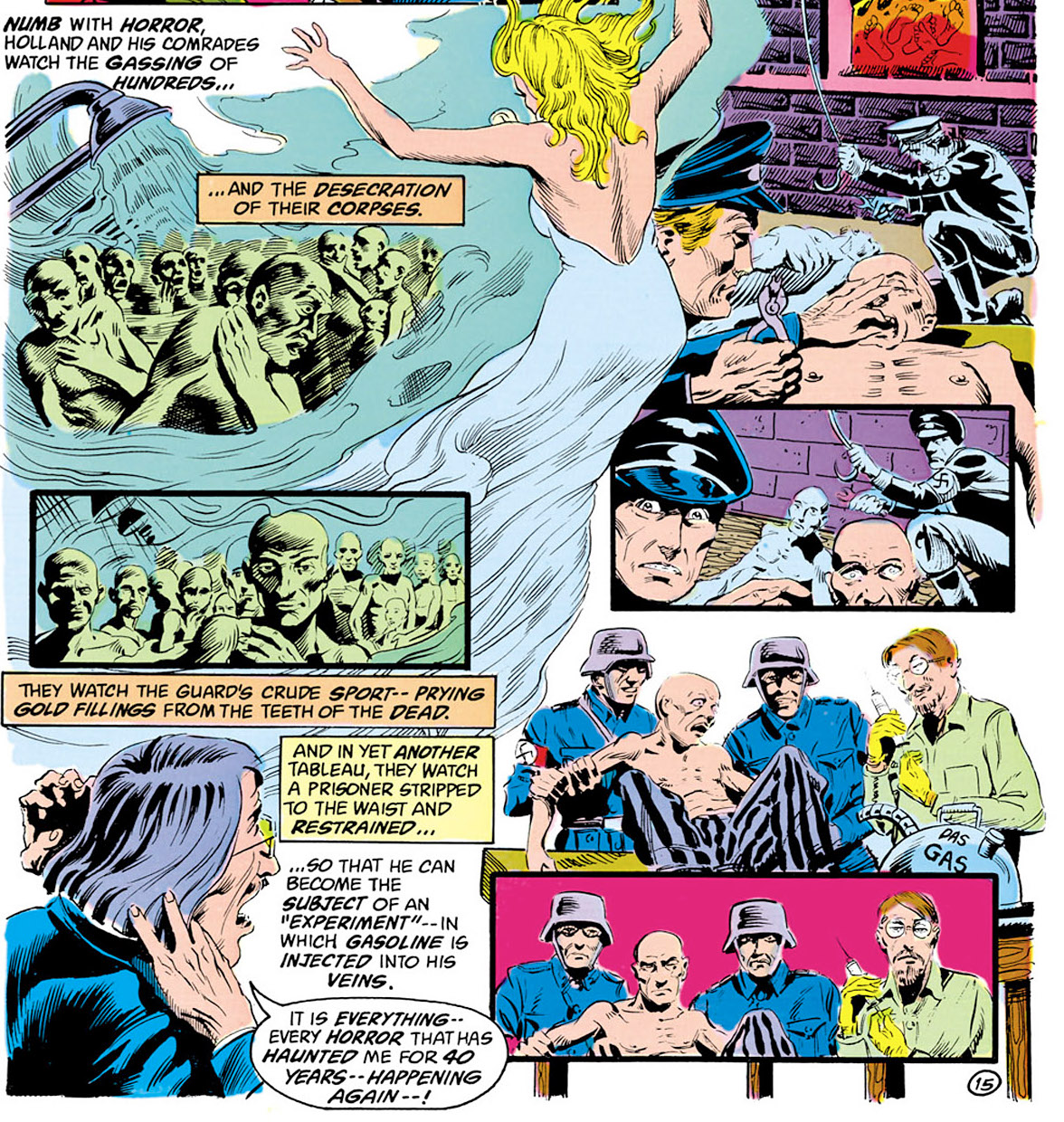

The coming of the Antichrist is very similar to the Nazi Holocaust. In fact, the Holocaust was a prelude to what Karen and the Antichrist are going to bring about. Neither Pasko or artist Tom Yeates sugar coat this. When Karen pulls the memories of an extermination camp out of Kripptmann’s head, we see Nazis pulling the gold fillings out of dead prisoners, Nazi doctors about to inject gasoline in a hapless prisoner’s veins. They are absolutely not fucking around with this story line. This is the motivation behind Kripptmann, and these two pages of terrible memories hammer home the reason he seeks personal redemption for his previous actions. It’s a fascinating drive for the character.

The coming of the Antichrist is very similar to the Nazi Holocaust. In fact, the Holocaust was a prelude to what Karen and the Antichrist are going to bring about. Neither Pasko or artist Tom Yeates sugar coat this. When Karen pulls the memories of an extermination camp out of Kripptmann’s head, we see Nazis pulling the gold fillings out of dead prisoners, Nazi doctors about to inject gasoline in a hapless prisoner’s veins. They are absolutely not fucking around with this story line. This is the motivation behind Kripptmann, and these two pages of terrible memories hammer home the reason he seeks personal redemption for his previous actions. It’s a fascinating drive for the character. The Swamp Thing is ultimately the agent that foils Hell's plan. Not the religious, not the powerful, but the swamp man who was once intervened to save a young girl, using power siphoned from Clancy. Even Kripptmann finds some measure of redemption by killing the man who would be the Antichrist. After the build-up, it’s a little unsatisfying, but the journey was well worth pursuing.

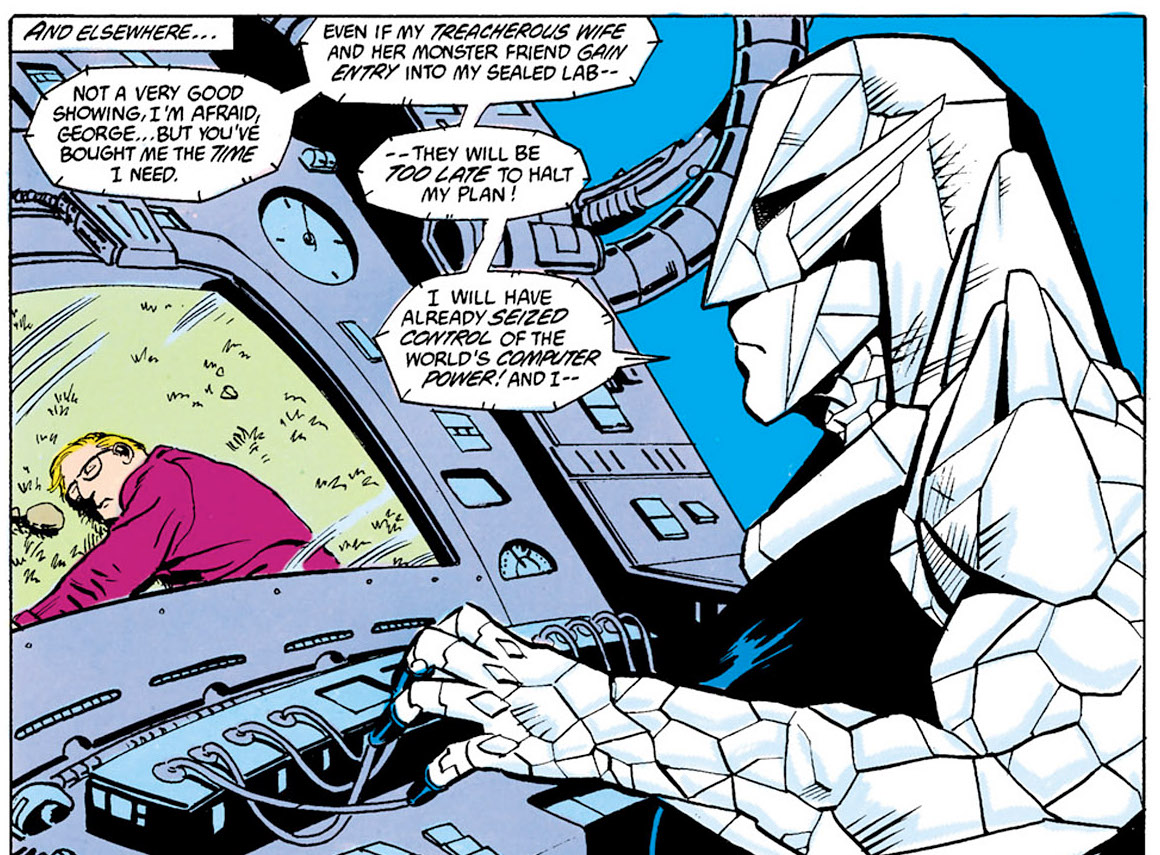

After this are two fill-in issues from Dan Mishkin, crossing over with the Phantom Stranger. It’s an mediocre, comic-booky technothriller, in which Nat Broder turns himself into pure silicon. Initially he goes on a rampage, turning many things, including Swamp Thing, into crystalline versions of themselves. Swamp Thing, fortunately, is still soaked with the bio-restorative formula, so he able to re-convert back to his mucky self. Broder turns out to also have power over computers, and in a few moments, takes over the world's computers. Eventually he is stopped by the combined forces of the Swamp Thing and the Stranger.

After this are two fill-in issues from Dan Mishkin, crossing over with the Phantom Stranger. It’s an mediocre, comic-booky technothriller, in which Nat Broder turns himself into pure silicon. Initially he goes on a rampage, turning many things, including Swamp Thing, into crystalline versions of themselves. Swamp Thing, fortunately, is still soaked with the bio-restorative formula, so he able to re-convert back to his mucky self. Broder turns out to also have power over computers, and in a few moments, takes over the world's computers. Eventually he is stopped by the combined forces of the Swamp Thing and the Stranger.Issue sixteen “Stopover In a Place of Secret Truths” introduces a few changes to the book. Abby Arcane from the original series returns. The story is a bit of a Twilight Zone style stand-alone, about a community that wears masks to hide hideous deformities. It also adds Kripptmann to the Swamp Thing’s traveling cast.

But more importantly, this is the first issue with John Totleben and Steve Bissette as artists. Now Tom Yeates is an amazing artist, and I should have talked about his work before. His work is very clean, nuanced, and full of unexpected little details. Yeates drew grotesque and the weird of the Swamp Thing series extraordinarily well. His art is strong, and developed amazingly as the series progressed. The climax of the Karen Clancy storyline would have been much weaker in the hands of a less-talented artist.

But more importantly, this is the first issue with John Totleben and Steve Bissette as artists. Now Tom Yeates is an amazing artist, and I should have talked about his work before. His work is very clean, nuanced, and full of unexpected little details. Yeates drew grotesque and the weird of the Swamp Thing series extraordinarily well. His art is strong, and developed amazingly as the series progressed. The climax of the Karen Clancy storyline would have been much weaker in the hands of a less-talented artist. This new team of Totleben and Bissette gave a frenetic, intricately detailed line art to the Swamp Thing that I fell in love with the instant I saw it. I love Bernie Wrightson’s art, but the Bissette/Totleben Swamp Thing art remains my favorite. The new team broke the art molds. No longer was the action confined to tidy boxes. Panels could be crystal-like shards that slashed diagonally across the page, sound effects could be reinforced with art, rather than being cartoonishly splashed across the page. In some ways, this is the punk element that appealed to me. While Yeates’ art is excellent the new team had a wild, uncontained, and unpredictable style. It didn’t march in staid array across the page but drew the eye in unexpected directions. This confrontational art style served Pasko's scripts very well, creating the atmosphere in which the words had more impact.

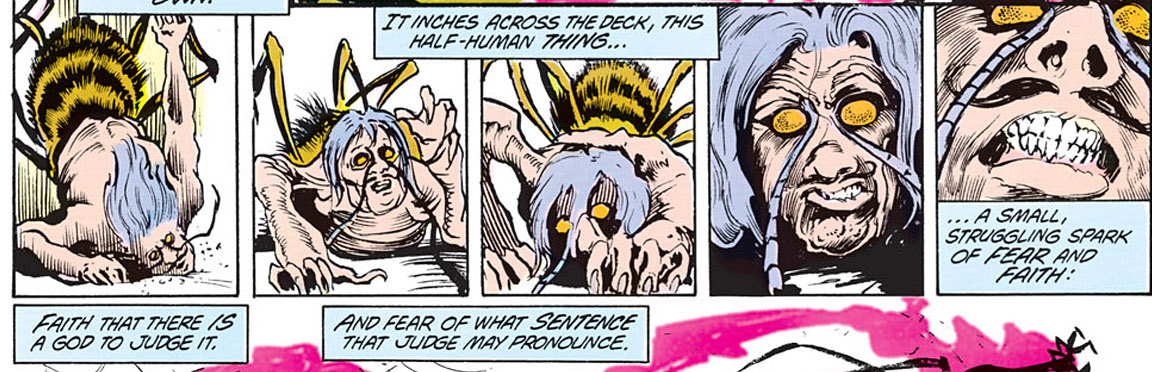

This new team of Totleben and Bissette gave a frenetic, intricately detailed line art to the Swamp Thing that I fell in love with the instant I saw it. I love Bernie Wrightson’s art, but the Bissette/Totleben Swamp Thing art remains my favorite. The new team broke the art molds. No longer was the action confined to tidy boxes. Panels could be crystal-like shards that slashed diagonally across the page, sound effects could be reinforced with art, rather than being cartoonishly splashed across the page. In some ways, this is the punk element that appealed to me. While Yeates’ art is excellent the new team had a wild, uncontained, and unpredictable style. It didn’t march in staid array across the page but drew the eye in unexpected directions. This confrontational art style served Pasko's scripts very well, creating the atmosphere in which the words had more impact. There is also a level of grotesquerie to Bissette and Totleben’s work that outstrips anything else I have seen in comics. Their monsters are carefully and patently impossible, with teeth that could never fit into their mouths. And they’re glorious. Art like this makes comics more effective than pure text, only a visual/text hybrid like comics could produce something that startling. Thankfully, we will get to see more of their art in Moore’s run.

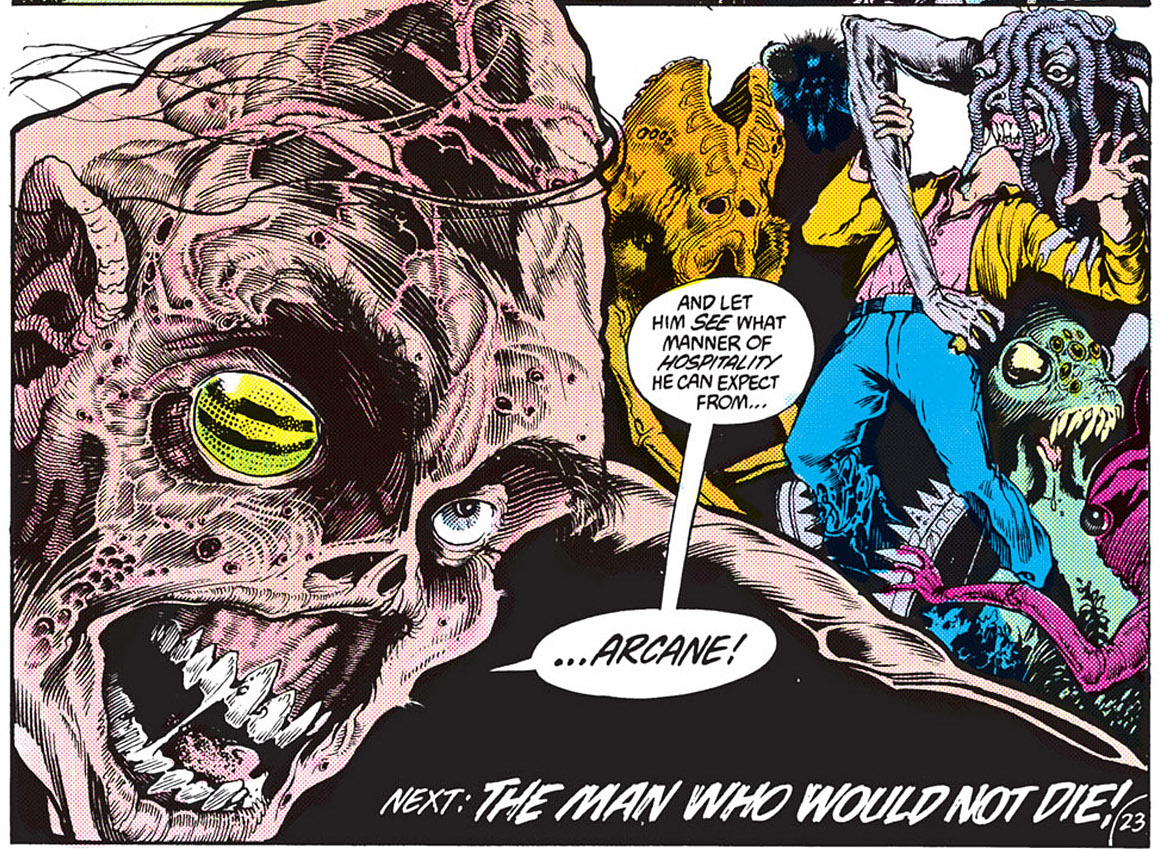

There is also a level of grotesquerie to Bissette and Totleben’s work that outstrips anything else I have seen in comics. Their monsters are carefully and patently impossible, with teeth that could never fit into their mouths. And they’re glorious. Art like this makes comics more effective than pure text, only a visual/text hybrid like comics could produce something that startling. Thankfully, we will get to see more of their art in Moore’s run.With Abbey reestablished, issue seventeen brings Matthew Cable back. And he’s a mess. A drunk, suffering from the aftereffects of electroconvulsive therapy, his life has been burned to the ground. But somehoe he has managed to gain some sort of psychic power. Which is kind of interesting, since Abby had started to developing powers in the original series. This is also the re-introduction of Anton Arcane. His is powerful and creepy, and this return cemented his place as Swamp Thing’s best recurring villain.

Issue eighteen “The Man Who Would Not Die” is a few new pages bookending the original resurrection of Anton Arcane, from back in the original Swamp Thing #9, and recolored. This is the first time I’ve seen the “Auntie Bellum” change to the script, and this has remained in every subsequent release.

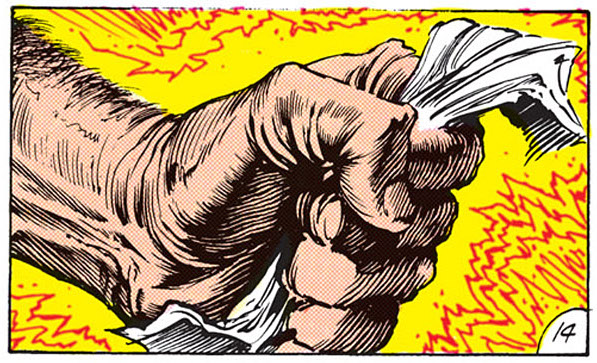

Issue eighteen “The Man Who Would Not Die” is a few new pages bookending the original resurrection of Anton Arcane, from back in the original Swamp Thing #9, and recolored. This is the first time I’ve seen the “Auntie Bellum” change to the script, and this has remained in every subsequent release.Issue nineteen “...And the Meek Shall Inherit...” is Pasko’s last, and it’s magnificent. Arcane and his un-men have taken on insect traits, making them even more grotesque than before. They capture Swamp Thing, Kripptmann, and Abby. Arcane still covets the Swamp Thing’s nearly-indestructable body. Kripptmann, a very gray and occasionally reprehensible character, redeems himself by destroying Arcane’s plans. At the cost of his life. His struggle, half-transformed into some sort of wasp or spider, is very small, but agonizingly illustrated by Totleben and Bissette. Pasko’s words are just right, giving the struggle a pathos seldom elicited in comics. With his sacrifice, Arcane is undone, and everyone separates. The stage is now set for Alan Moore’s tenure.

Pasko’s work on Swamp Thing has gone unrecognized for more than thirty years, and that’s a shame. It’s certainly overshadowed by Moore’s years on the book, but these are excellent, creepy comics that pull the reader into a shadowy realm of modern horror. He literally draws the Swamp Thing out of the Gothic and comic-book trappings that defined the character in the initial series and presents us with fully modern horror. Going back over these comics is a pleasure, because Pasko’s writing is subtle and complex, different from what was being written then, and different from what’s being written now. It’s absolutely worth re-visiting for modern readers or horror, for its mood, its complex characters, and refusal to tie the end of the story up in a bow. Personally, I love the way the stories do not let the reader off the hook, but force us to look at issues and ideas from which the stories germinated. This is comics at their best. Telling stories that do not condescend to the reader.

Pasko’s work on Swamp Thing has gone unrecognized for more than thirty years, and that’s a shame. It’s certainly overshadowed by Moore’s years on the book, but these are excellent, creepy comics that pull the reader into a shadowy realm of modern horror. He literally draws the Swamp Thing out of the Gothic and comic-book trappings that defined the character in the initial series and presents us with fully modern horror. Going back over these comics is a pleasure, because Pasko’s writing is subtle and complex, different from what was being written then, and different from what’s being written now. It’s absolutely worth re-visiting for modern readers or horror, for its mood, its complex characters, and refusal to tie the end of the story up in a bow. Personally, I love the way the stories do not let the reader off the hook, but force us to look at issues and ideas from which the stories germinated. This is comics at their best. Telling stories that do not condescend to the reader.Next up, Roy Thomas once again pays homage to his favorite character. Somewhere I never would have expected it. Thanks for your patience, and I’ll write more soon.