I would be remiss if I did not include what is considered the first appearance of a giant monster in film, George Melie's À la conquête du pôle (The Conquest of the Pole). In it, a frost giant attacks the party, consuming (and then regurgiating) one of its members.

The anmation of the large puppet is pretty good; the eyes, brows, and ears wiggle, the mouth moves. The professors react in the same way as all humans confronted with gigantic monsters; they fire at it, to no effect. Only when a canon is brought to bear does the giant leave off snacking. It is not killed, however, but withdraws from the noise and smoke of the canon.

But The Frost Giant really didn't have much influence on Godzilla, or many other giant monsters. The construction technique is very different, it is not central to the film, and it has very little personality. The monster is in it's own territory, rather than trespassing on the the realm of mankind.

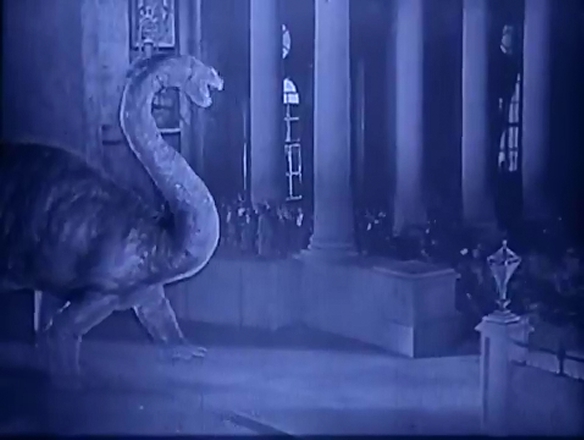

The oldest film that had the most lasting effect on Godzilla, and giant monster film in general, is the 1925 The Lost World, with dinosaurs animated by Willis O'Brien. This is, rather famously, a film greatly loved by Rays Harryhausen and Bradbury. Dinosaurs and humans share the screen effortlessly, thanks to O'Brien's pioneering use of split screen.

The Lost World was the first very successful dinosaur film, and the first international success of Willis O'Brien. As I discuss Godzilla's ancestry, Willis O'Brien and Eugène Lourié will consistently crop up.

O'Brien's work in The Lost World is meticulous and fascinating. For this film, he incorporated bladders into several the models, allowing them to simulate breathing. His attention to detail and desire to make each model have its own personality serves him well here, but much more so in King Kong, since the big ape has a lot more screen time. The amount of time the film devotes to dinosaurs is impressive. They first appear 36 minutes into the film, and the model sequences are pretty consistent from then on. It's one of the most extensively special-effects films filmed up to that point.

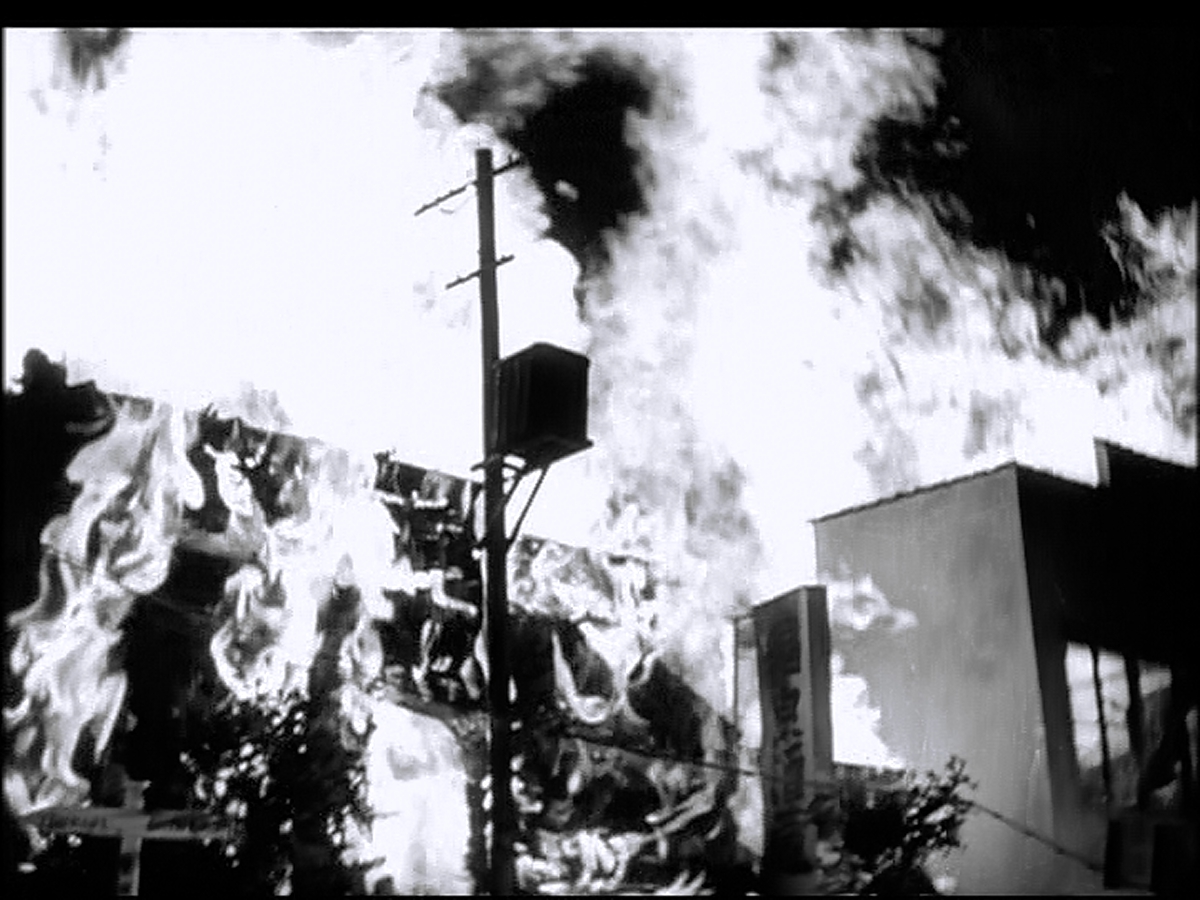

After an hour's worth of adventures on the Plateau of Dinosaurs, Professor Challenger manages to apprehand a sauropod and bring it back to London. In the book, his capture was a pterodactyl, but the brontosaur was a much better idea for on-the streets mayhem. In the Crichton/Speilberg film, it is escalated again to a T-Rex. Kong-style (but off-screen) it gets loose and rampages for five muinutes at the climax of the film. People panic, fences are stomped, a building smashed, all before it crashes through Tower Bridge and into the Thames. Back in its element, it swims off, one of the few giant monsters to survive its inital clash with mankind.

This is an enormously influential sequence, and will be referred to by Willis and his protegee Harryhausen several times. Images and scenes that are repeated or imitated include mother and child in the path of the onrushing giant monster (later seen in King Kong). The dinosaur is intrigued by the street lamp, as the Rhedosaur is intrigued with the lighthouse and fog horn in Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. Tower Bridge is prominently featured, then damaged, as it would be in Gorgo. The brontosaur sticks its head in a window, the way Kong puts his hand into a window. Fleeing men and women turn to the underground for safety, as they do in Godzilla, Godzilla Raids Again and Gorgo, while monster's heavy tread causes debris to rain down.

In this five-minute sequence, the seeds are laid for the first generation of giant monster films. The beast runs amock, people flee in panic, and destruction ensues. Godzilla Raids Again changes the dynamic of the genre, adding the opponent for the monster to fight, but so many of the films I'll be discussing, from Beast from 20,000 Fathoms to Cloverfield take their inspiration, directly or indirectly, from this sequence.

Next week, the Big Ape. With a quick side digression about a plumber.