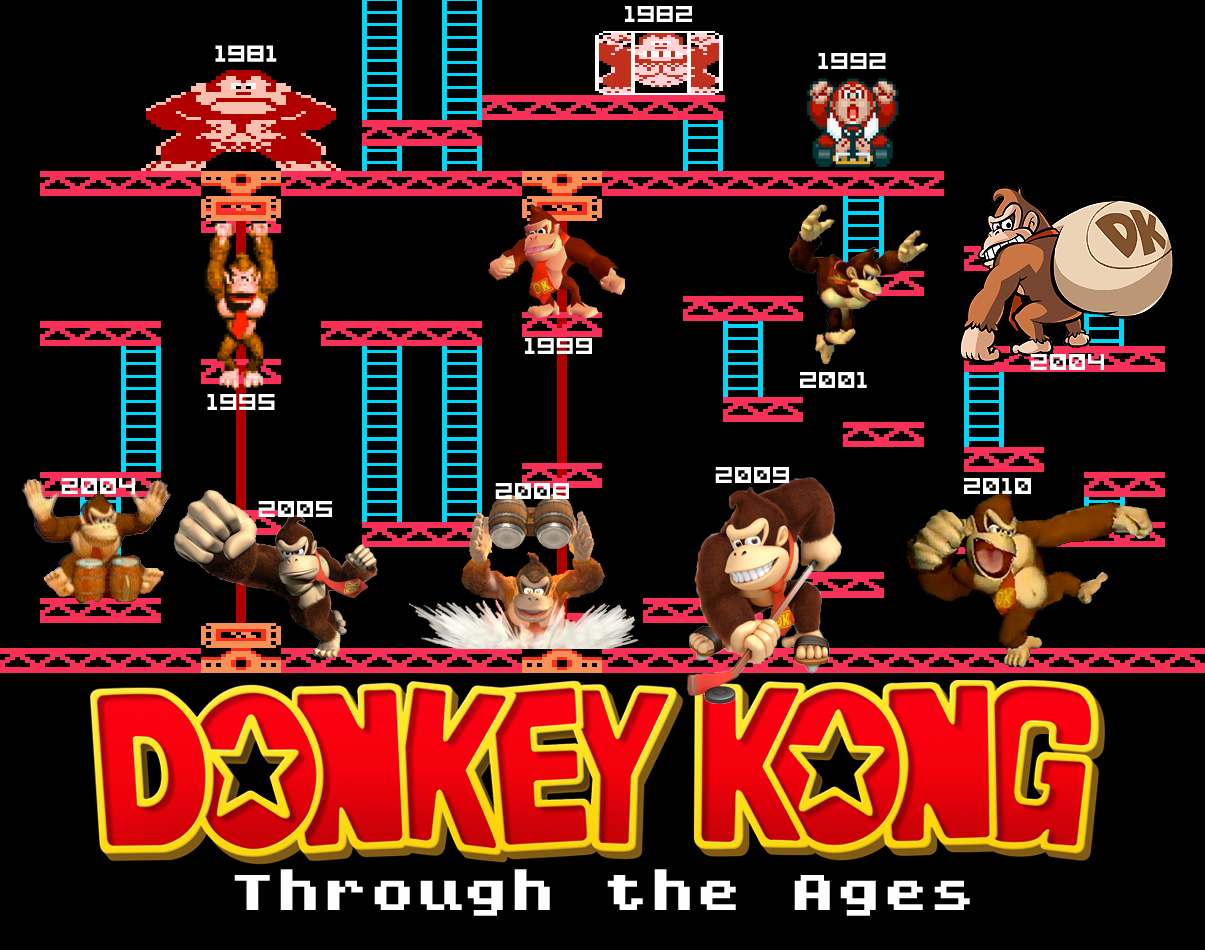

This is the first of three giant monster films created by Eugène Lourié, who felt with each film that he was being increasinly pigeonholed. Which is a pity: Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and Gorgo are delightful monster films. I'll be discussing The Giant Behemoth next week. The fim's monster was the work of Ray Harryhausen, pupil of Willis O'Brien, who brought Kong and The Lost World's dinosaurs to life.

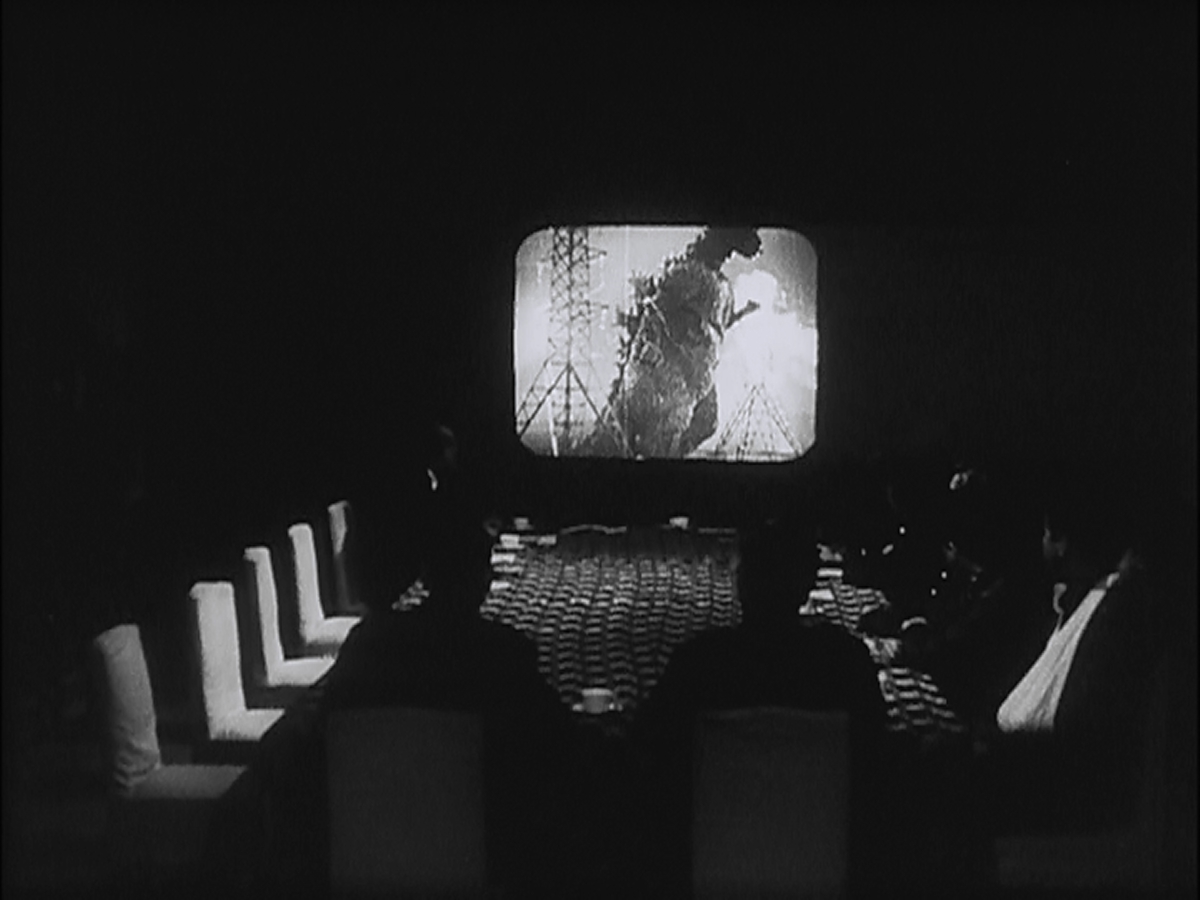

The rhedasaurus is the first giant monster to be precipitated by a nuclear detonation, a film trope that would continue throughout the 60's and 70's. The explostion is shown through a bright flash, and then stock footage of a Bikini atol detonation. Godzilla had to make do with just the bright flash, but the panic brought on by the unexpectedness of the blast gives the scene more fear than Beast, since the witnesses are all men of science who are expecting it. This is a national difference between the American and Japanese experience with nuclear weapons. To Americans, they are a tool, an experiment. To the Japanese, they are weapons of fear and destruction. Rhedasaurus is not nuclear powered, nor scarred or angry. It was merely woken by the nuclear test.

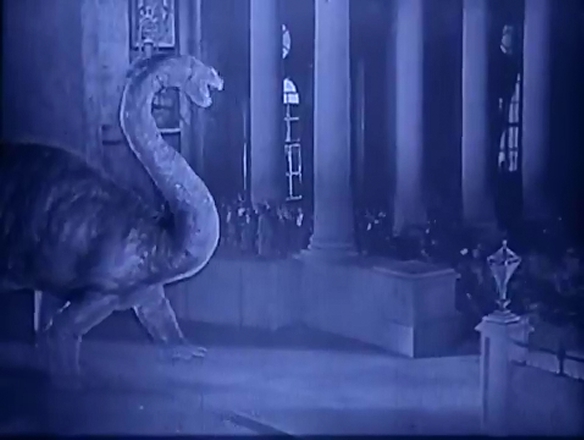

Nine and a half minutes into the film, the beast is first glimpsed. Beast from 20,000 Fathoms is not ashamed of its monster, perfectly willing to give the audience a preview to whet their appetite for the inevitable city-based rampage. Interestingly, the Beast's first victim is not killed by an attack, but by an avalanche brought on the by the beast's passing. No malice or hunger involved, the human simply was in the wrong palce at the wrong time, emphasizing the destructive capacity of the beast. It is from a different time, and its presence in the modern world is disruptive and deadly.

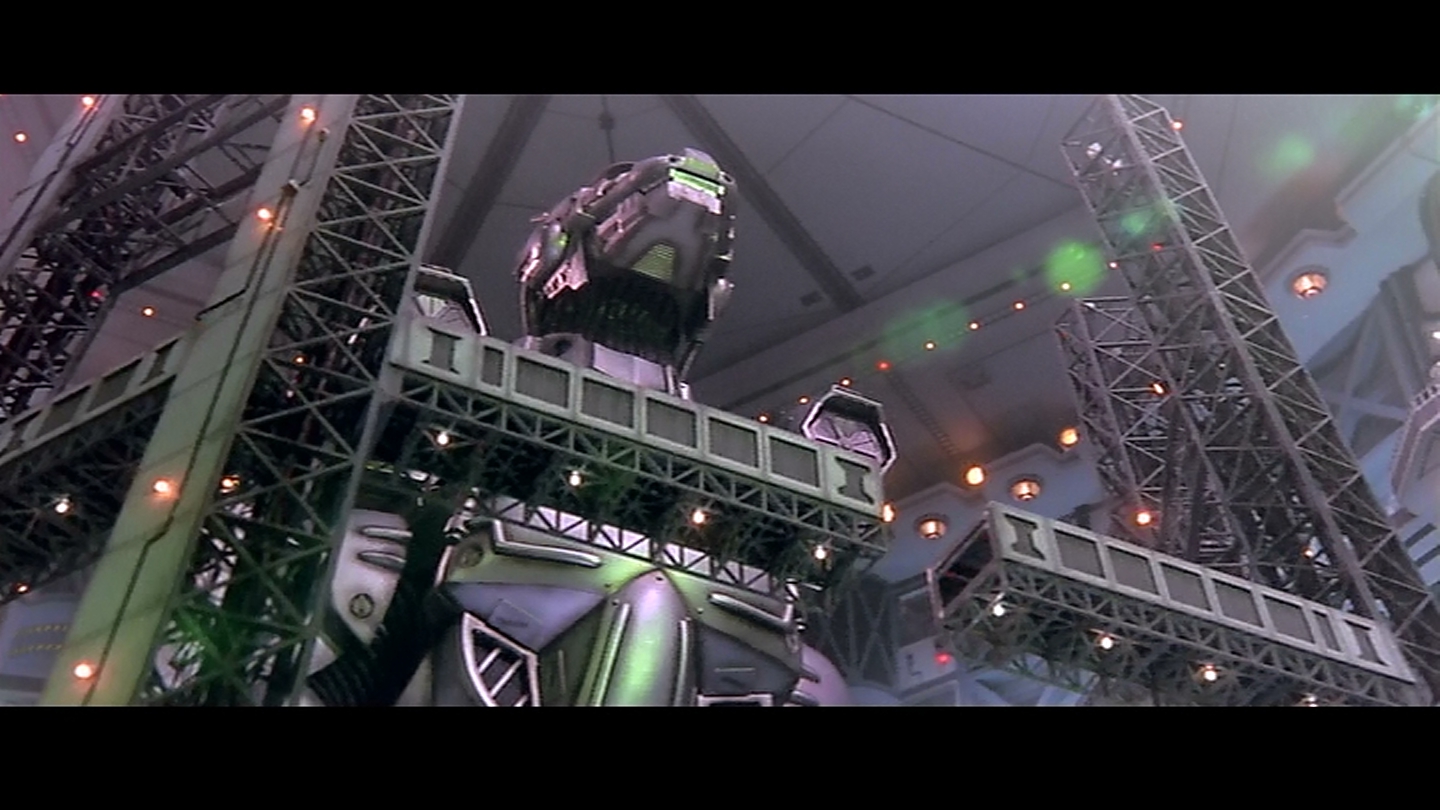

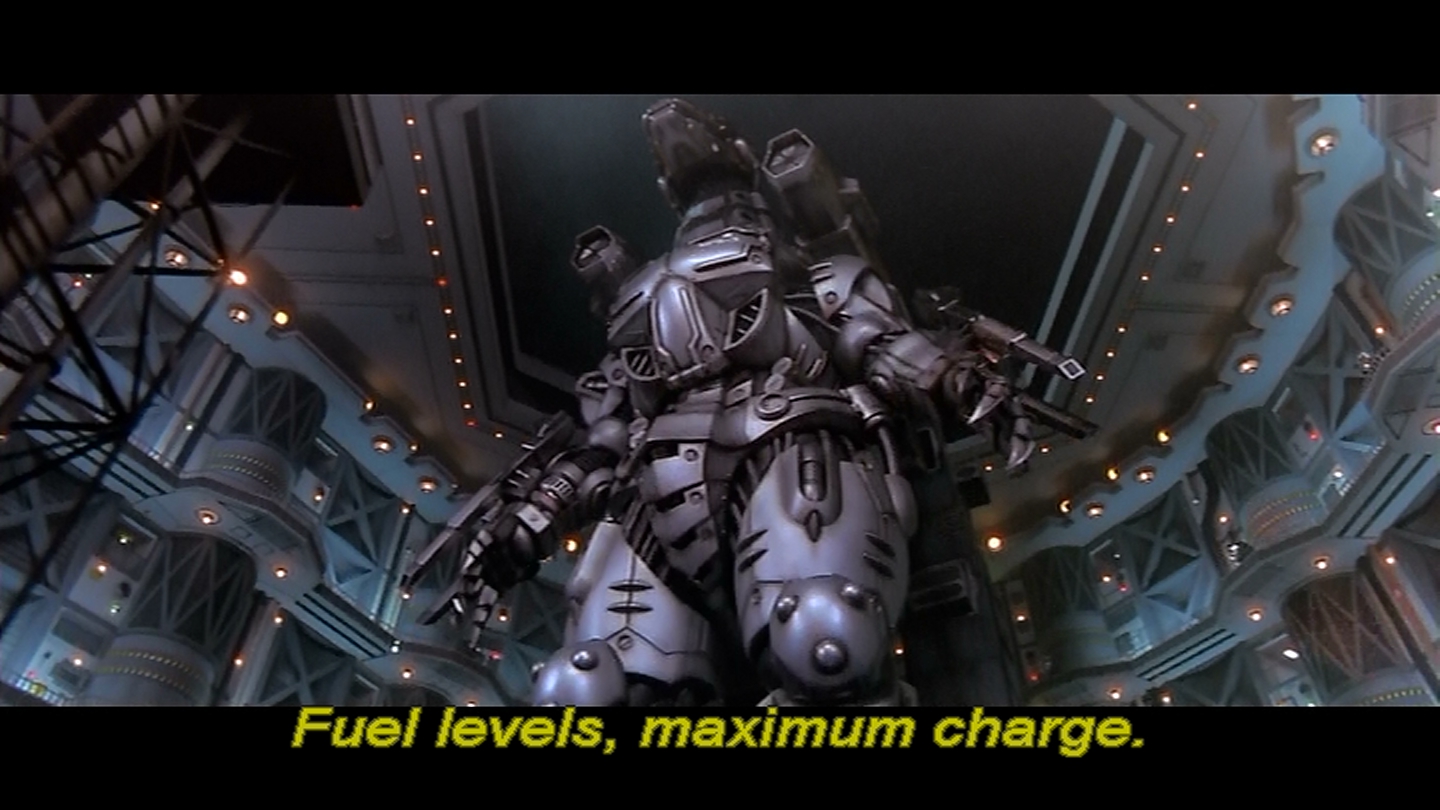

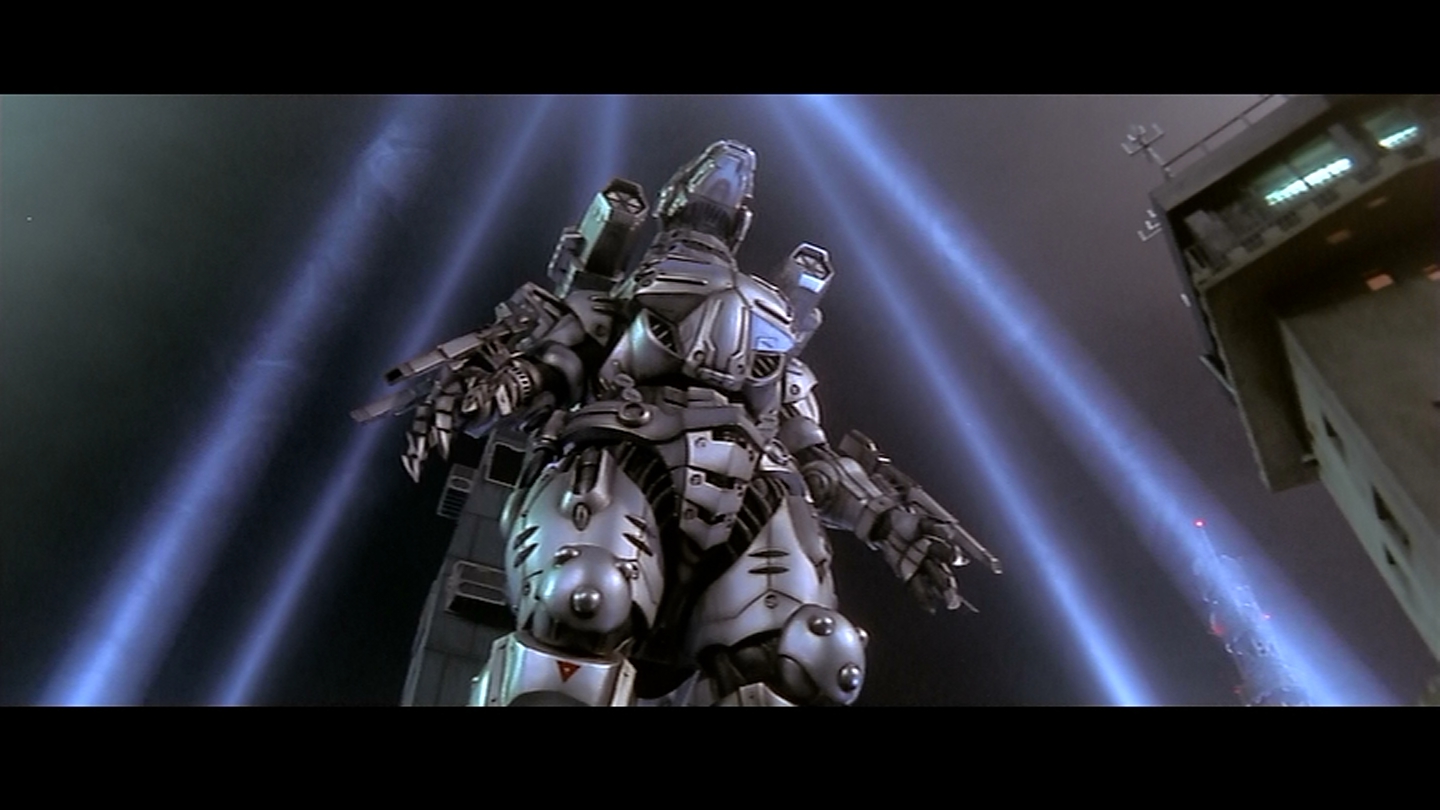

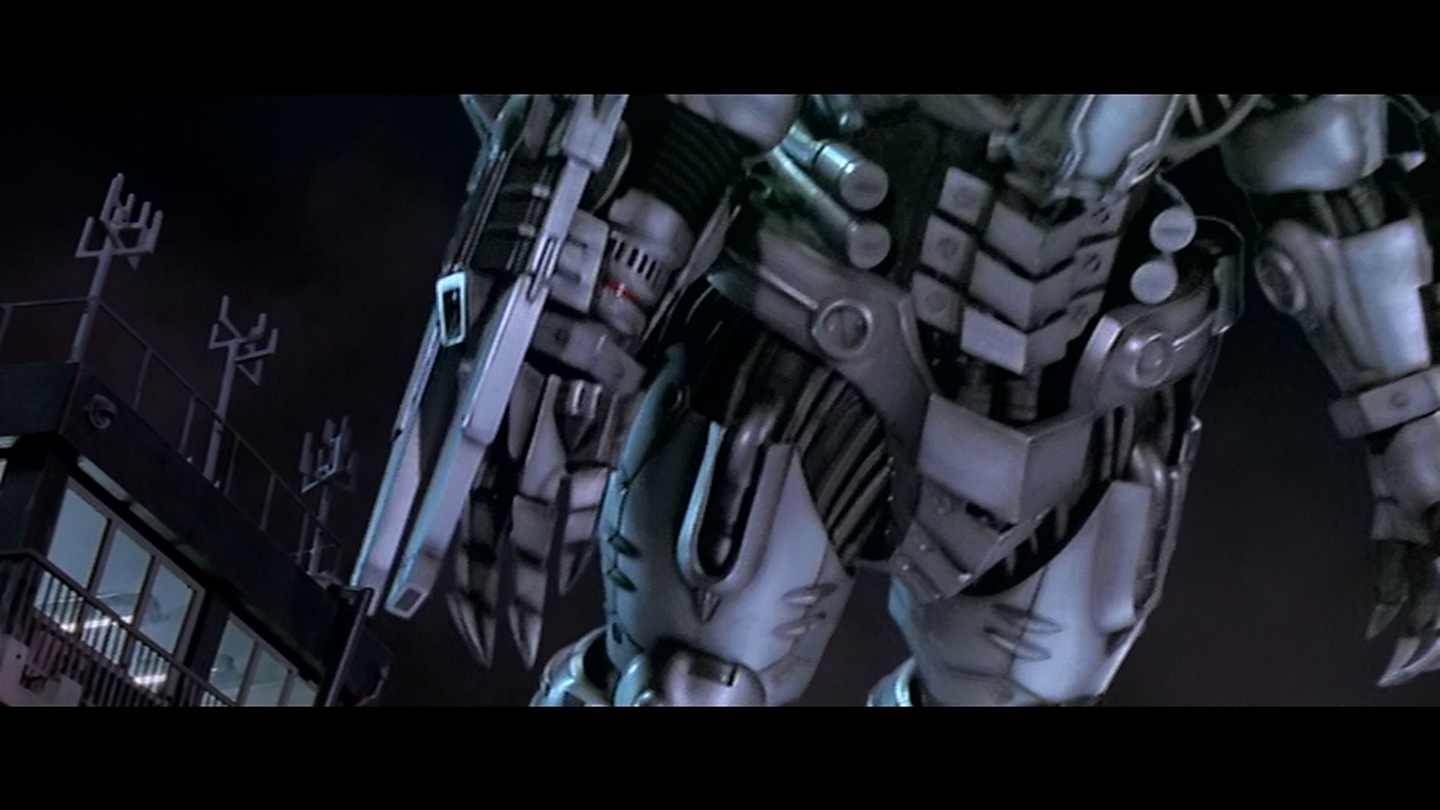

The rhedasaurus is a magnificent fictional dinosaur. Low-slung on four legs, it does not stand like Godzilla, and can be more aggressive than Lost World's bronotosaur. As with Kong, when the rhedasaurus is on the screen, nothing else is as interesting. All the memorable moments in the film are at the end, during the city-destroying rampage. Harryhausen's technique is every bit as good as O'Brien's, although he does not utilize shots quite as complex. Given the more limited budget of Beast, there are no full-scale mock-ups of any part of the rhedasaurus, forcing Harryhausen to use a small stable of tricks to show interaction between the monmster and the landscape. He does this by picking a car out of a traffic jam of mixed real and miniature cars, deceving the eye aso to where the miniatures begin. When crowds are fleeing into the subway, the Beast rushing toward them, the famous Flatiron Building behind them all.

Other events recur in Godzilla. The military attempts to stop the rhedasaurus with high-voltage wires. We also get a scene in a hospital, where doctors talk about the ancient disease the Beast has. As they talk, they minister to dying patients, and several muffled forms on stretchers are carried bhind them. This moment is the only one in which we see the suffering of those the Beast comes in contact with. Again, this was handled with much more emotional punch by Ishiro Honda.

Structurally, the film The film begins, and is aped by the later Gamera with an arctic nuclear test. The rhedasaurus then smashes a fishing vessel, as Godzilla will do next year. However, Godzilla, rather than leaving the destruction as it was, showed the effects on families and community, showing us the haunted eyes of mothers and sisters whose men would never come home. Godzilla also redefines the protagonist triad of two professors and the pretty female assistant to two professors, a pretty daughter, and a working man, effectively splitting the Tom Nesbitt role into two different characters; Dr. Serizawa, the brilliant scientist, and Hideto Ogata the man of action. Ishiro Honda didn't seem to believe in two-fisted professors.

As is common in science fiction films, the amateur gets to explain how the monster came to be in a hypothetical fashion, in order for it to be dismissed by the “expert”. This allows the information to be handed to the audience, even as it's fantastic and improbably nature is highlighted. And the audience can feel relieved when the world-renowned experd changes his mine and endorses the crackpot theory. After all, he's world-renowned! Professor Elson also makes sure that we know he's about to go on his first extended vacation in 30 years. The Simpsons' portmanteau &lquot;retirony&rquot; seems appropriate here, although Elson does spend his last moments gazing into the mouth of a living specimen of what he has studied for many years.

Beast from 20,000 Fathoms seems caught in between exultation of science, with action professor Tom Nesbitt, and fear of technolgy and scientific advancement, since atomic testing awkaned the creature. But the plusses outweigh the negatives in this case, since a rare radiactive element is what brings the Beast down, delivered by the military (Lee van Cleef, demonstrating that he can shoot and kill damn near anything). As always, it's interesting to look at the film showcasing the technology of the day. The radio announcer, the banks of telephone operators, all are delightfully indicative of the tim period. One of my pleasures when watching a series of Godzilla films is watching the city's height increase from film to film.

Beast from 20,000 Fathoms is a pretty good film. Ray Harryhausen's work on the rhedasaurus is arresting and interesting, and the staging of the its scenes are meticulous and fascinating. A good monster film, highly influential, and essential to anyone who wants to understand the history of giant monster film.

Next week, same director, smaller budget. But tomorrow, I'll be seeing Pacific Rim. If my head explodes I've left strict instructions that someone is to blog about it.