Gamera was the creation Daiei studios, who had worked with Akira Kurosawa to create Roshamon. Unlike Godzilla, who began as a metaphor, Gamera was intended from the beginning to be a child-friendly giant monster money-maker. Many tropes were already established, and but Daiei's films found their own path, borrowing from Godzilla and other giant monster films rather than apeing them. Daiei would continue to make a Gamera film a year until running out of steam after Gamera vs Zigra in 1971.

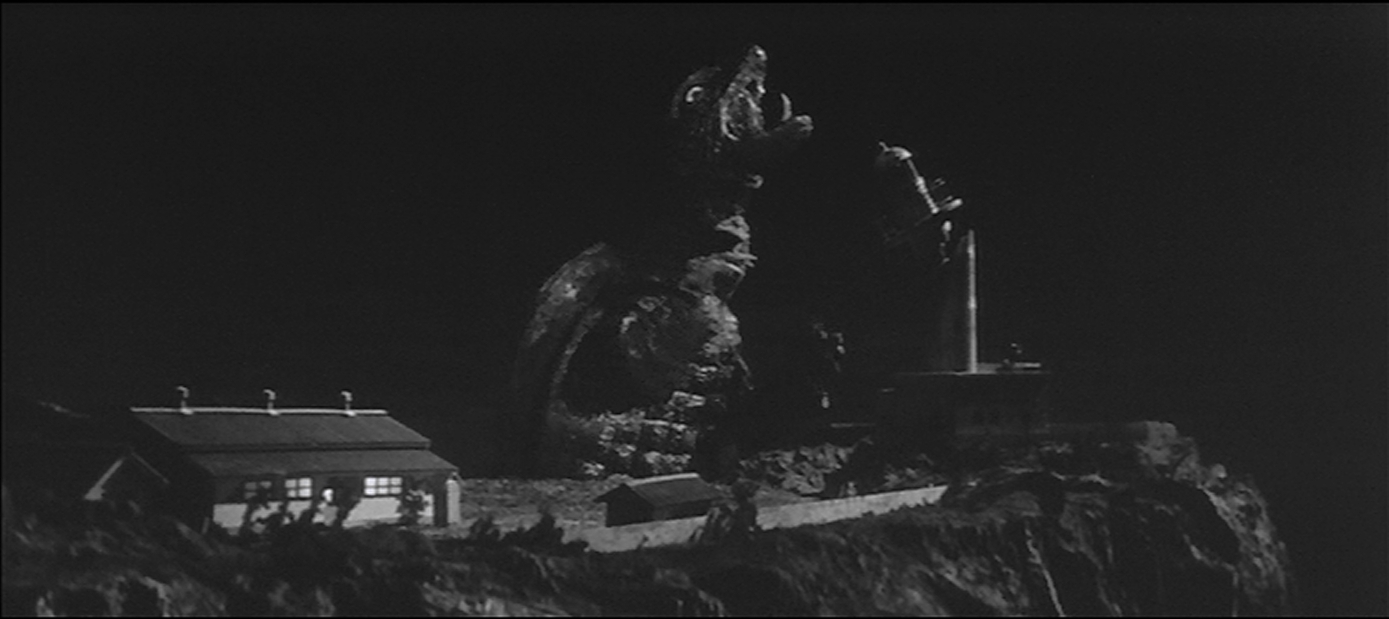

Giant Monster Gamera draws a great deal from Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. From the nuclear/Arctic origin to a scene with a lighthouse, Gamera is more little brother to Godzilla, striving to catch up to big brother's achievements, than a direct spawn of the Godzilla franchise. However, the competition allowed the two franchises to swap ideas back and forth. Toho watched the success of Gamera, and began aiming their Godzilla films at a younger audience, and began including children in the stories. Daiei lacked Toho's Eiji Tsubaraya, with his eye for perfection and innovation. Daiei also wasn't willing to commit as much money as Toho, even in the middle sixties, when Toho budgets were plummeting. So the miniatures work is not nearly as compelling.

There are nods to the 1954 Godzilla as well. Gamera's head appears over an ice ridge, threatening the Chidori Maru, in a similar way to Godzilla's first appearance over the creast of a hill. Dr. Hidaka expfresses sentiments similar to those of Dr. Yamane in Godzilla and Dr. Elson in Beast, that it would be sad to destroy such a unique specimen. The first attempt to destroy Gamera is with high-voltage wires, which we saw in Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, Godzilla and Gorgo. And once the atypical geothermal plant has been destroyed, Gamera heads for the classic location: Tokyo.

In many ways, Gamera the Giant Monster is a throwback, more like something that would have come out in the fifties, rather than 1965. The film is black and white, and the monster is alone. We have the prototypical monster's rampage with no opposing monster to stop it. In one of the few more modern touches, there is a disco scene, with the careless, goofy kids dancing away before the police come in and tell them to evacuate. Ignorant and uncaring, the kids won't stop their sock-hop. They are unprepared when Gamera crushes the building.

According to David Kalat, the -ra ending, which ends so many giant monster names (Mothra, Ghidora, Ebira) serves the same function that -zilla has achieved in English. And since the name is Gojira in Japan, he makes a good case. So Gamera is literally Turtle-zilla.

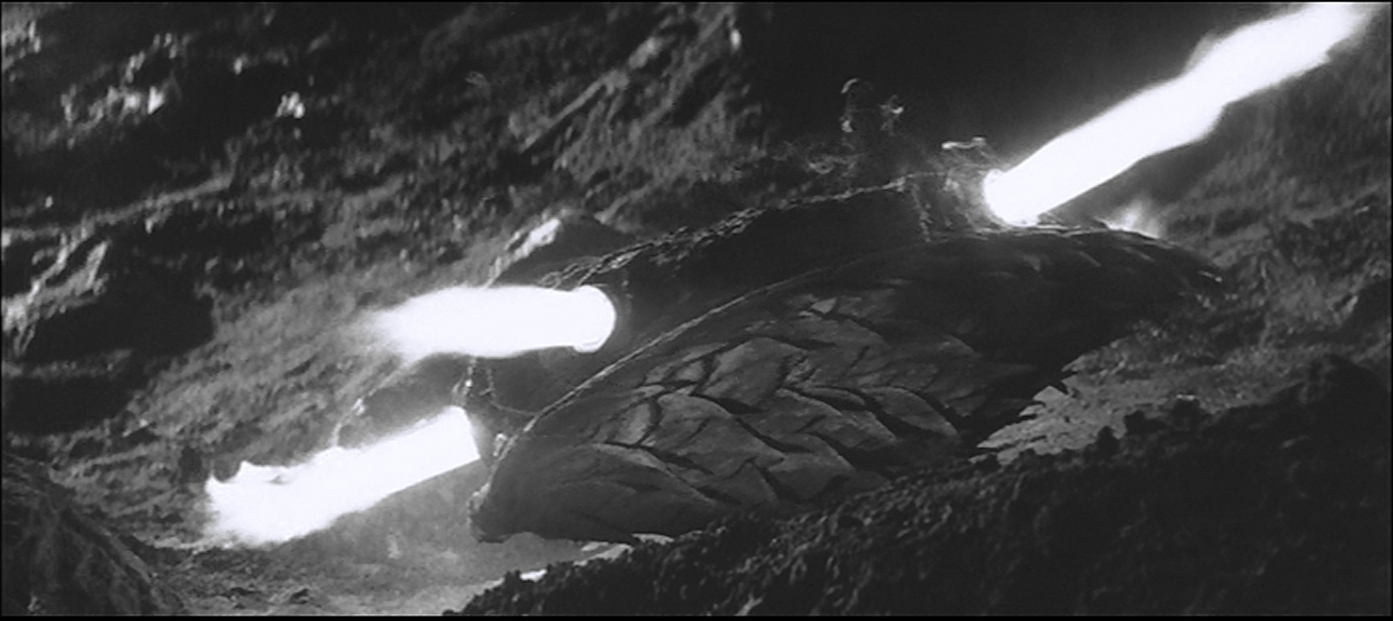

Unlike Godzilla, Gamera was not created as a nuclear metaphor, although with heightened tension of the arms race, writer Nisan Takahashi (who would write all of the Gamera films until 1980) can certainly be excused for including nuclear weapons, even if they only serve, as with Beast from 20,000 Fathoms to awaken the giant beast. Gamera has some sort of thin backstory about being a gigantic turtle from Atlantis, but this is not well developed. Everyone is quite astonished when Gamera shoots jet flames out of the holes in its shell, but there's no explanation for this, either.

There seems to be a religious subtext within Gamera. I find it strange and unlikely that an Inuit would be wearing a cricifix, even more so as he's doing so outside his anorak. It may be a sign of foreignness. Fortunately, he has a stone from Atlantis, which explains that Gamera is the Devil's Envoy.

Enter Toshio. Toshio is the kid, and there will be kids in all the subsequent Gamera films, and several Godzilla films. This film doesn't pander so much to the kids, but the low point of Godzilla's franchise comes when child actors are used. Toshio is a turtle-obsessed kid who has trouble making friends. As a turtle-obsessed kid who had trouble making friends myself, I still can't muster up much sympathy for the character. He's clearly deluded, his conclusions very much contradicting that action that's happening on-screen. Gamera appears, and while the adults are frightened, Toshio is excited. He is, I suppose a stand-in for the intended audience, who love giant monsters. But Toshio has no expectation of getting killed, where we as the audience do not live in a universe where gigantic turtles destroy Tokyo. Toshio's actions in the film therefore seem delusional, unattached to what is happening around him. On seeing Gamera, he runs up the lighthouse to greet him face-to-face, but Gamera knocks the lighthouse down. Fortunately, he catches Toshio, demonstrating his dual role as building-destroying monster that is kind to kids. In another attempt to meet Gamera face-to-face he catches a ride on an oil car that is about to be fed to the monstrous terrapin. Gamera reaches for the car, there's an explosion, and miraculously, Toshio and the guy trying to rescue him are on the ground, unhurt. But Toshio constantly says Gamera is a good turtle, and than he's only acting this way because people are attacking him. The statement doesn't hold up well, especially after we watch Gamera breathe flames on a building-full of adults.

The set piece in which Gamera destroys the geothermal plant is pretty good. And it marks the very brief intervention by the military. Toshio insists that Gamera doesn't mean to be bad, but what else do you do with a gigantic, invulnerable turtle that's eating the local fire?

Gamera's Tokyo rampage is less impressive. He smashes buildings, tromps on overpasses, crushes highways. Unlike Godzilla, who doesn't breathe fire on civilians any more, Gamera opens a building, exposes the cowering humans, and then pours fire down on them. If Toshio is right and Gamers doesn't mean to be bad, he's sure not making any friends. And since director Noriaki Yuasa directed both the live action special effects sequences, we can rule out a miscommunication between the two portions of the script.

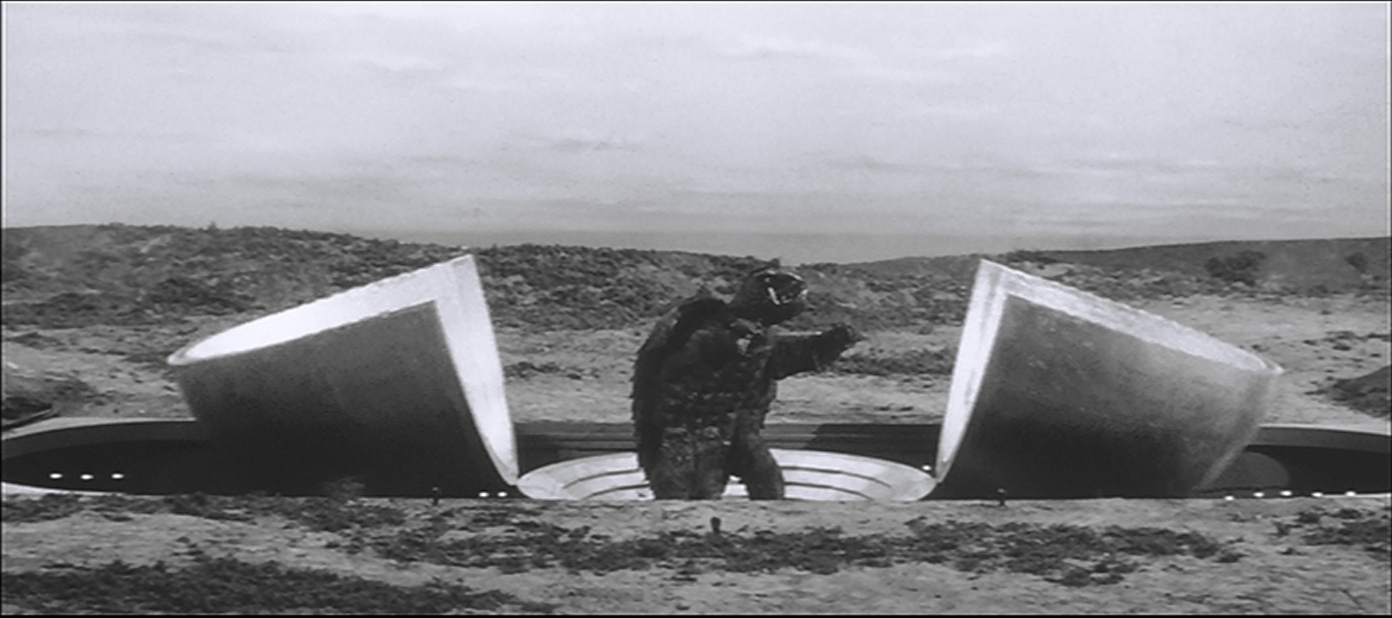

A third set piece happens at a petroleum refinery, and serves as a perfect example of the difference between a Tsuburaya production and one of Daiei's. The sequence starts of well, with the oil tanks burning and the occasional explosion. The rail line starts to send cars full of oil down the track to Gamera, who stands at the end of the railhead. The problem is, he's not doing anything. Not destroying, not looking around, just waving his hands around, waiting for his oil to be delivered. When a long line of oil tankers is presented to him, he pulls them in. When he's not doing that... he's just standing at the end of the rail head, waving his arms. He does the same when captured by the Plan Z platform. He moves to it, then stands there, waiting for the plot to happen.

With the military once again demonstrated as useless, the scientists must turn to science to save Japan. They decide to load Gamera into a gigantic rocket and shoot it off the Earth. This is called "Plan Z." Again, the absurdity of lifting something as heavy as a 60-meter turtle with a rocket is completely glossed. And off to Mars goes Gamara. Science has triumphed.

Giant Monster Gamera is a better film without the terrible dub job, but it's still not a good film. It's really only an acceptable monster film. Gamera has his fans, and that's fine, but I'm not one of them. Sixties and seventies goofiness is something I can take only in small doses, and Gamera is just full of thoughtless little pieces. Is Toshio right about Gamera? Without Toshio, Gamera is pretty much an ordinary monster film. With the child actor that is supposed to represent the audience's interest in the film, the weird Atlantean origin story that goes nowhere, the surprise deployment of jets from his shell, and the lack of attention to background detail, the film feels like one of those SyFy jobs that got slapped together. Nobody loved it. Nobody sat down and thought about what this meant. Things happen for the sake of happening.

Next week, the clock ticks over to 1966, when Daiei produces more kaiju than Toho, Frankenstein's monster gets a clone, and I discuss a lost film from another continent.

No comments:

Post a Comment