For convenience, I'll be breaking this discussion of the Heap into three sections, each one concerning each of the three volumes. Although the tenor of the stories does not change precisely with each volume, it breaks the stories down into more digestible chunks.

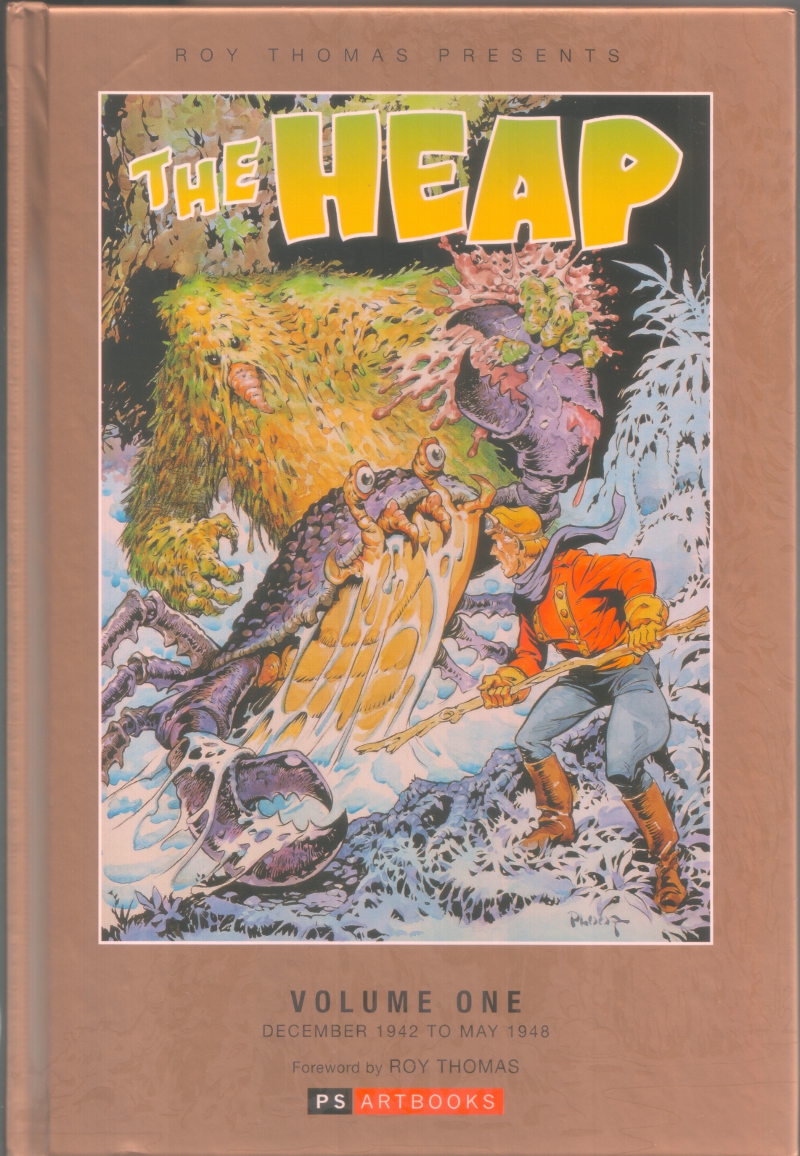

For convenience, I'll be breaking this discussion of the Heap into three sections, each one concerning each of the three volumes. Although the tenor of the stories does not change precisely with each volume, it breaks the stories down into more digestible chunks.First, it should be said that the Heap is likely a tribute to the Theodore Sturgeon story "It". "It" first appeared in a 1940 issue of Unknown magazine. "It" is an excellent Sturgeon story, and involves a dead man who rises as a plant-like hominid, its intelligence clouded, to wreak havoc on a small backwater town. The main difference between the Heap and It is that the Heap has a specifically WWI flier origin, and It dissolves in water, ending the story. "It" would later be adapted to comics by Roy Thomas in 1972, right at the beginning of the Swamp Monster boom. I'll talk about that in due course.

The Heap started out as a one-off appearance in a Sky Wolf story. Comics in the forties were collections of stories, from eight to sixteen pages, rather than one long story, which is more common now. This allowed an individual issue to appeal to a broader audience. Someone would potentially buy the comic because they followed one of those stories. Fans of Sky Wolf and Airboy would both buy an issue of Air Fighter Comics.

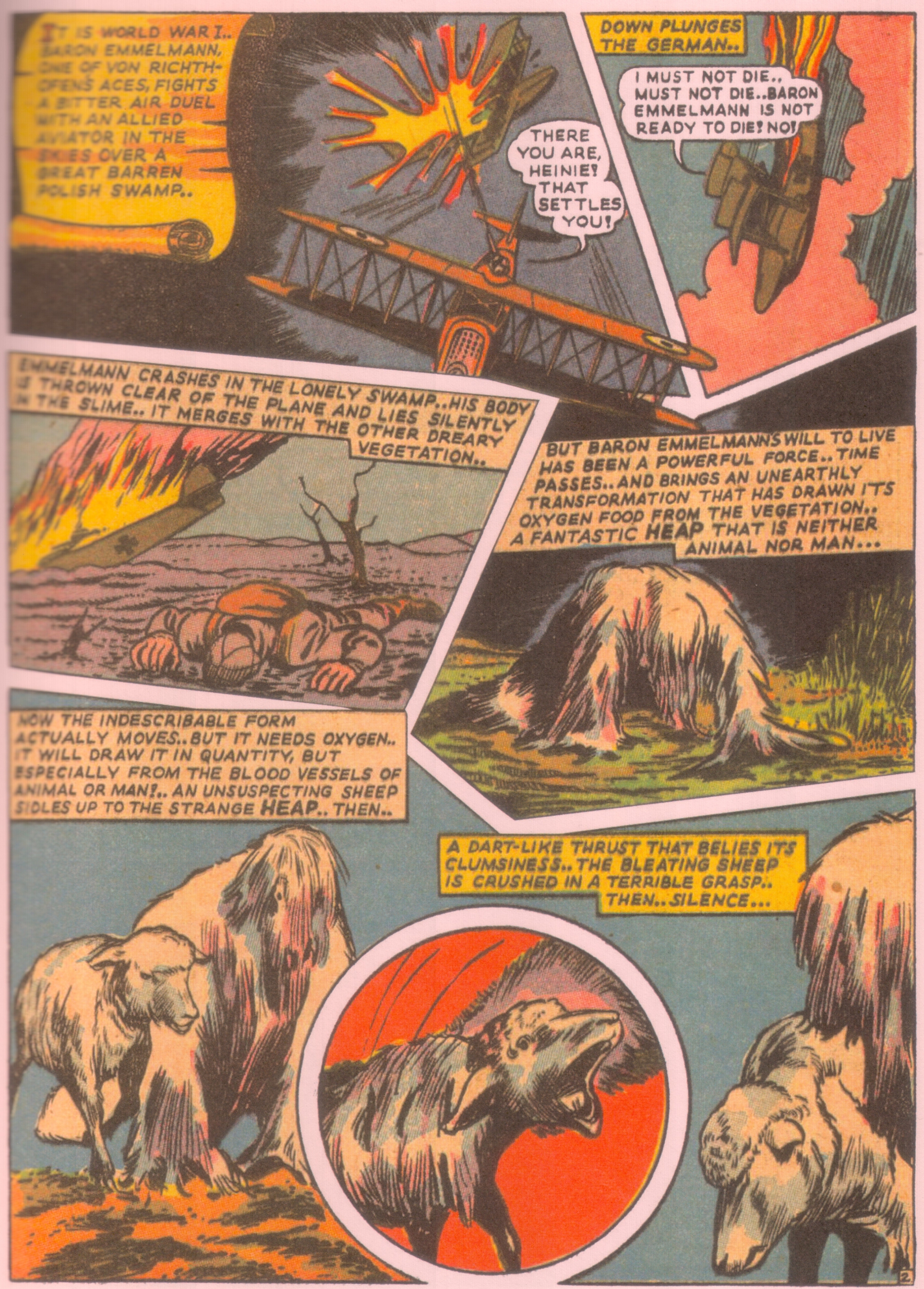

The first Heap story, from the third issue of Air Fighter Comics also contains the Heap's origin story, told in four brief panels, of a WWI German pilot. Baron von Emmelmann is shot down over a Polish swamp. His incredible will to live does not let him die, so for unexplained reasons, he becomes a man-shaped plant. Unlike the later Swamp Things, the Heap cannot speak, and only barely remembers its past as von Emmelmann. The amount any given muck monster remembers of its past life varied. This origin is recounted many times, even in this volume of twenty-four initial stories. And a WWI flight nerd notices that Emmelmann is flying a different plane every time the story is recounted, or wonder what a German flier is doing engaging an Eastern-front plane over Poland. Still, this origin remains consistent, and the character is well-defined at this origin. The Heap is inhumanly strong, immune to bullets, and although it cannot think, it has emotional reactions to things from its past. Initially, it is said to get oxygen by sucking the blood of animals, but this falls by the wayside fairly quickly, as do its fangs.

The first Heap story, from the third issue of Air Fighter Comics also contains the Heap's origin story, told in four brief panels, of a WWI German pilot. Baron von Emmelmann is shot down over a Polish swamp. His incredible will to live does not let him die, so for unexplained reasons, he becomes a man-shaped plant. Unlike the later Swamp Things, the Heap cannot speak, and only barely remembers its past as von Emmelmann. The amount any given muck monster remembers of its past life varied. This origin is recounted many times, even in this volume of twenty-four initial stories. And a WWI flight nerd notices that Emmelmann is flying a different plane every time the story is recounted, or wonder what a German flier is doing engaging an Eastern-front plane over Poland. Still, this origin remains consistent, and the character is well-defined at this origin. The Heap is inhumanly strong, immune to bullets, and although it cannot think, it has emotional reactions to things from its past. Initially, it is said to get oxygen by sucking the blood of animals, but this falls by the wayside fairly quickly, as do its fangs. The initial four stories, published between December 1942 and May 1946, ostensibly star Sky Wolf, a rogue Allied flier who flies against the Nazis, and at least once, against the Japanese. The first three stories are war stories, while the fourth seems like a calculated transition to get the Heap to America. After this, Airboy Comics (which changed its name from Air Fighter Comics to reflect its breakout star in December, 1945) would publish one Heap story every issue. These initial stories are less than stellar. The Heap interferes with Iron Ace's plans to capture Sky Wolf, allowing Sky Wolf to escape the Nazi's nefarious clutches. Aside from the Heap, it's a pretty by-the-numbers plot. The second story, from Air Fighter Stories #9 is more less generic. The Heap begins stealing and flying aircraft all over the front, wrecking both Allies and Nazi airbases. Sky Wolf must take care of the problem. But it's strange to see the Heap flying planes.

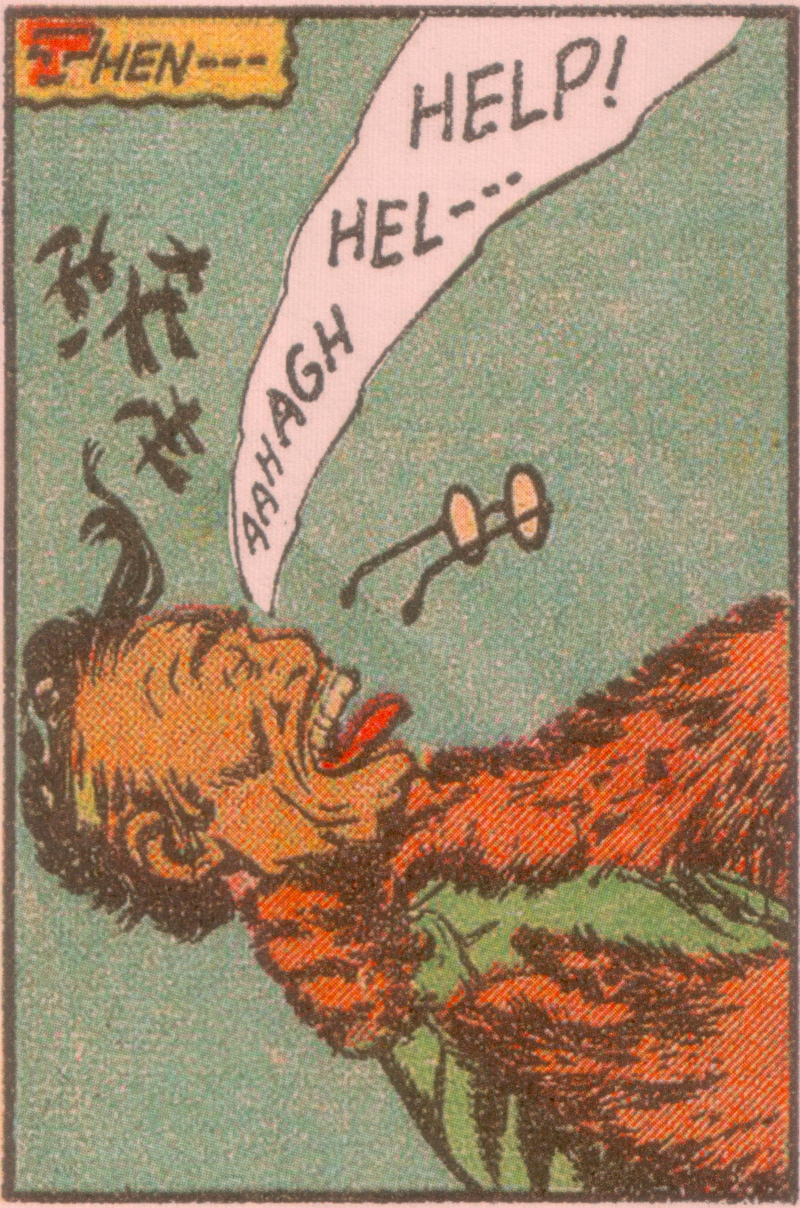

The initial four stories, published between December 1942 and May 1946, ostensibly star Sky Wolf, a rogue Allied flier who flies against the Nazis, and at least once, against the Japanese. The first three stories are war stories, while the fourth seems like a calculated transition to get the Heap to America. After this, Airboy Comics (which changed its name from Air Fighter Comics to reflect its breakout star in December, 1945) would publish one Heap story every issue. These initial stories are less than stellar. The Heap interferes with Iron Ace's plans to capture Sky Wolf, allowing Sky Wolf to escape the Nazi's nefarious clutches. Aside from the Heap, it's a pretty by-the-numbers plot. The second story, from Air Fighter Stories #9 is more less generic. The Heap begins stealing and flying aircraft all over the front, wrecking both Allies and Nazi airbases. Sky Wolf must take care of the problem. But it's strange to see the Heap flying planes.  Air Fighter Comics V. 2 #10 contains the third, and perhaps most interesting of the Sky Wolf and Heap stories. The Heap finds its way to occupied China, the art is pretty 1940's racist. The Heap is also brown, for some unknown reason, where it had been white before. With one exception, it would remain brown until 1948, when he would unexpectedly shift to green. There's also a surprising amount of killing. The Heap strangles the evil Japanese commander right before our eyes. Killings would become more commonplace in the Heap, and are still surprising to someone who grew up reading comics that had to be approved by the Comics Code Authority.

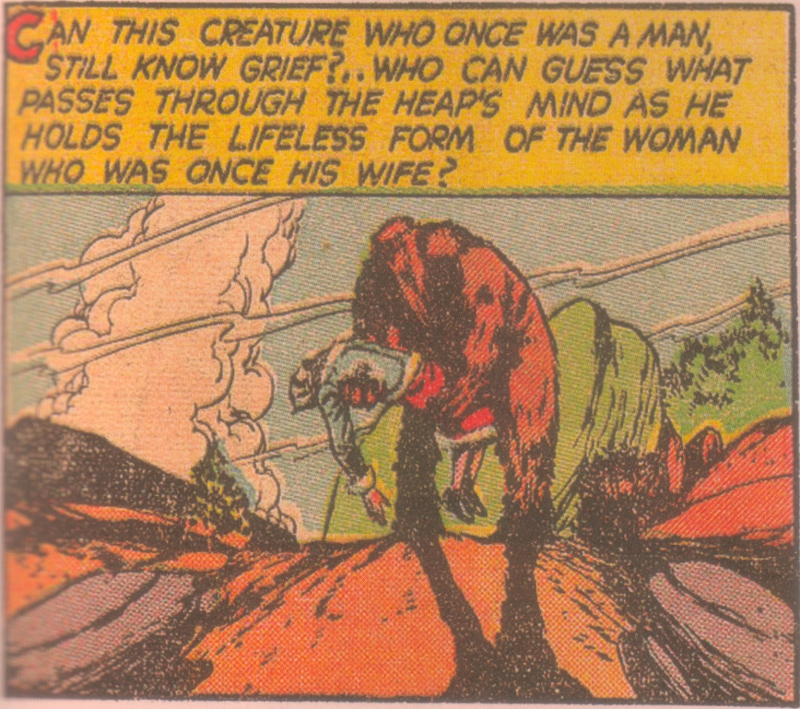

Air Fighter Comics V. 2 #10 contains the third, and perhaps most interesting of the Sky Wolf and Heap stories. The Heap finds its way to occupied China, the art is pretty 1940's racist. The Heap is also brown, for some unknown reason, where it had been white before. With one exception, it would remain brown until 1948, when he would unexpectedly shift to green. There's also a surprising amount of killing. The Heap strangles the evil Japanese commander right before our eyes. Killings would become more commonplace in the Heap, and are still surprising to someone who grew up reading comics that had to be approved by the Comics Code Authority.  But this story also provides us with our first real taste of pathos. His wife, the Baroness von Emmelman, has been providing humanitarian aid to the Chinese. As is inevitable in this sort of plot, the Heap attempts to protect her, but a bullet intended for him kills her. This is echoed in Len Wein and Bernie Wrightson's Swamp Thing # 1. And for the first time, a story keys in on the theme that later swamp creatures like Man-Thing and Swamp Thing will possess in abundance, the pathos of loneliness and loss. Similar themes have kept Mary Shelley's Frankenstein in print for nearly two hundred years.

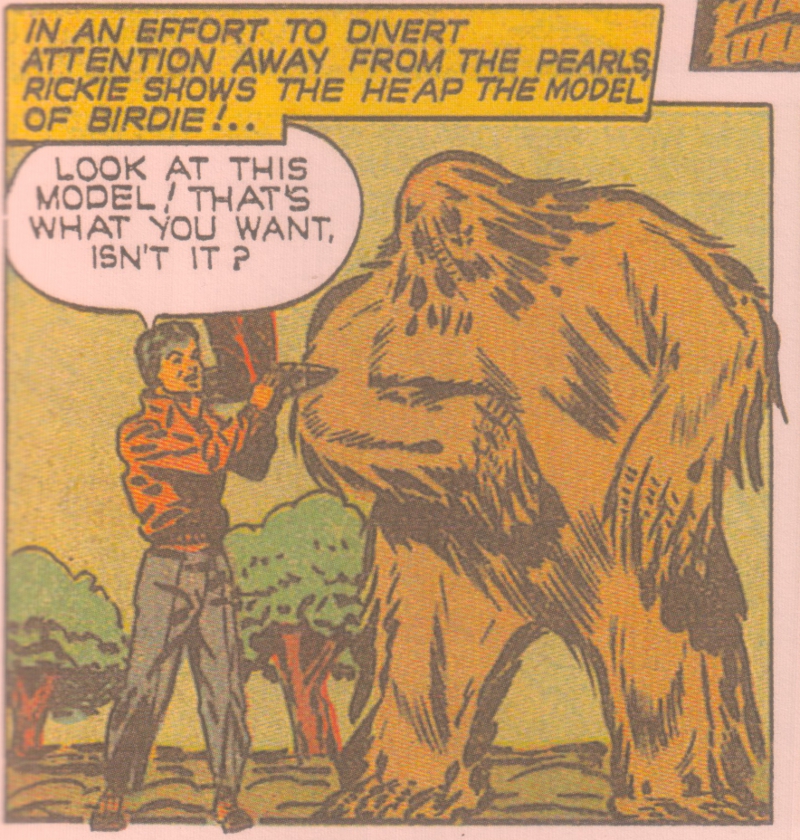

But this story also provides us with our first real taste of pathos. His wife, the Baroness von Emmelman, has been providing humanitarian aid to the Chinese. As is inevitable in this sort of plot, the Heap attempts to protect her, but a bullet intended for him kills her. This is echoed in Len Wein and Bernie Wrightson's Swamp Thing # 1. And for the first time, a story keys in on the theme that later swamp creatures like Man-Thing and Swamp Thing will possess in abundance, the pathos of loneliness and loss. Similar themes have kept Mary Shelley's Frankenstein in print for nearly two hundred years. Once the war was over, Sky Wolf faded from the pages of Airboy Comics, but the Heap remained popular. Believing that the audience wouldn't sympathize with the inhuman Heap, or perhaps wishing to provide structure for the stories to come, Hillman's writers invented Rickie Wood, an adolescent whose love of model airplanes enticed the Heap to imprint on him, allowing a tenuous connection with the Airboy Comics' air fighter theme. But the Heap was a regular feature now, one story would appear in every issue of Airboy Comics until Hillman stopped publishing comics in 1953.

The Rickie Wood stories quickly become the sort of crime comics that proliferated in the forties and fifties, until Wertham and the Comics Code Authority decided comic books should only be used for moral instruction. Gangsters attempt to steal fortunes or murder people, and it always comes down to Ricki and the Heap to set things right. The Heap acts as the avenging hand of God, or the writer's moral sensibility, giving the bad guy his just desserts at the end of the story. The Heap is usually just a little-seen presence in his own story. The crime stories owes a lot to the hard-boiled genre, and contain less of the weird horror sensibility that the character would later display. There are plenty of fedora-wearing gangsters shooting people, and a lot of dames with impressive builds and bare midriffs.

The Rickie Wood stories quickly become the sort of crime comics that proliferated in the forties and fifties, until Wertham and the Comics Code Authority decided comic books should only be used for moral instruction. Gangsters attempt to steal fortunes or murder people, and it always comes down to Ricki and the Heap to set things right. The Heap acts as the avenging hand of God, or the writer's moral sensibility, giving the bad guy his just desserts at the end of the story. The Heap is usually just a little-seen presence in his own story. The crime stories owes a lot to the hard-boiled genre, and contain less of the weird horror sensibility that the character would later display. There are plenty of fedora-wearing gangsters shooting people, and a lot of dames with impressive builds and bare midriffs.As a fan of weird horror, I find these stories are disappointing. They are often formulaic, and represent cheap pulp work. Rickie's ability to keep the Heap tailing after him grows tired after a few stories, and it's unsatisfying to see the Heap acting as a in Rickie's stead in the final act of the story. And the writers appeared to know this, since the Heap changed directions completely a year later. But they are a step away from the very pulpy war stories, and small steps toward the more Gothic stories to come later.

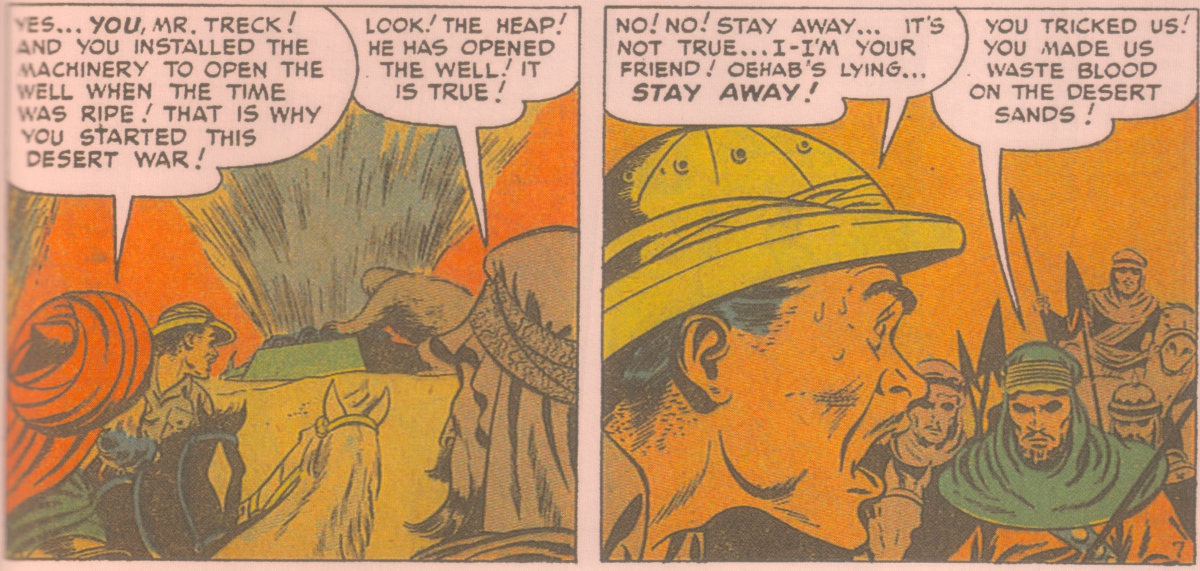

There are only three Heap stores that include the Roman Goddess Ceres and her rival Ares, but they're very unusual. The Heap's origin is not rewritten, but is given a magical underpinning. The goddess Ceres chose the Heap to be her champion of Nature, an idea that Alan Moore would pick up many years later in his Saga of the Swamp Thing. This is not the most interesting thing about the stories, however. Now cut off from narrative leash Rickie Wood, the Heap roams the globe, and in an unusual move for forties pulp, two of the stories address colonialism in a time when it really wasn’t discussed. The antagonists are white males exercising corrupt authority over native populations (Arab, and an odd sort of African/Polynesian that I find difficult to recognize). Firther, the heap doesn't serve as the direct instrument of comeuppance, beating up or killing the antagonist. Instead it is instrumental in showing the native populations the duplicity of the greedy. The natives are left to their own devices when determining their oppressor's fate.

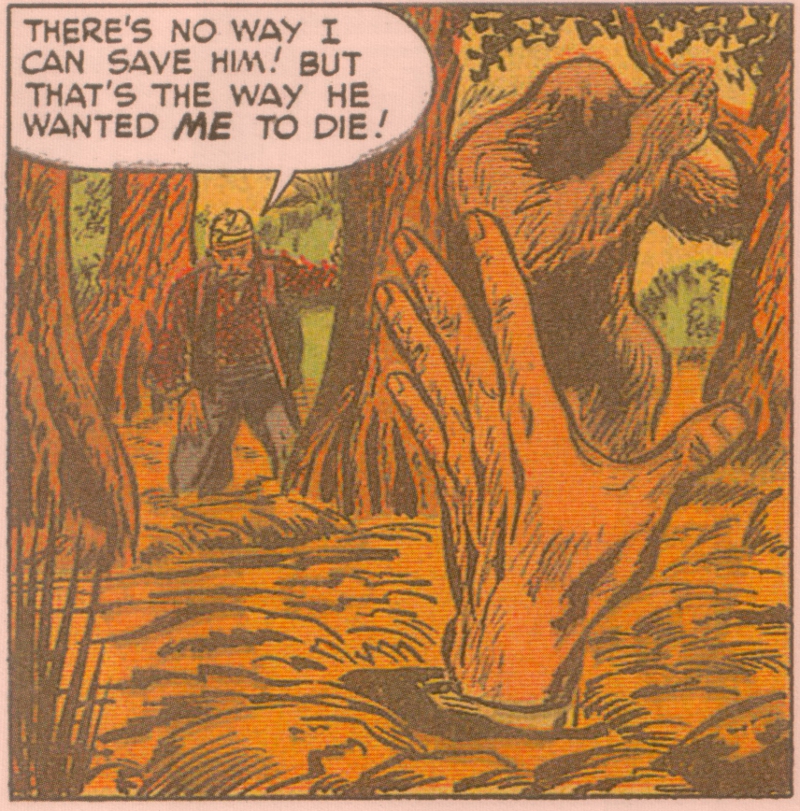

Apparently, these stories did not prove to be popular, because they only lasted three issues. The next stage of the Heap's narrative development kept the world-traveling, but dropped the overtly supernatural figures of Ceres and Ares. These, the last five stories in Volume One, return to the crime themes and ideas of the Rickie Wood era. But they are more interesting. First of all, they lack Rickie Wood, and the bland suburban America that he as a narrative device is tied to. The exotic settings mean that the stories have more freedom to introduce fantastic elements, such as man-eating plants. And again, the Heap does not serve as the violence of justice being served, but instead is more of a plot element that allows the ending to happen in a satisfactory way. This is the approach that Steve Gerber very successfully took when writing Man-Thing. It's a radical and inventive way to tell a comic story, since the Heap is not the protagonist of the story. Instead, it is a catalyst.

Apparently, these stories did not prove to be popular, because they only lasted three issues. The next stage of the Heap's narrative development kept the world-traveling, but dropped the overtly supernatural figures of Ceres and Ares. These, the last five stories in Volume One, return to the crime themes and ideas of the Rickie Wood era. But they are more interesting. First of all, they lack Rickie Wood, and the bland suburban America that he as a narrative device is tied to. The exotic settings mean that the stories have more freedom to introduce fantastic elements, such as man-eating plants. And again, the Heap does not serve as the violence of justice being served, but instead is more of a plot element that allows the ending to happen in a satisfactory way. This is the approach that Steve Gerber very successfully took when writing Man-Thing. It's a radical and inventive way to tell a comic story, since the Heap is not the protagonist of the story. Instead, it is a catalyst.The exoticism of the stories also lends them additional interest. The Heap ends up in a South American plantation, where a scheming cousin is attempting to steal the family inheritance from the feisty Estella. The Heap helps a gold prospector escape from a series of double-crosses, his duplicitous partner drowning in quicksand. An Indian story-teller weaves a tale of a Nazi fugitive being brought to justice.

Once the Heap as catalyst had been established as a pattern, the Heap stories begin on the path to the Gothic, and the stories start firing on more cylinders. The later stories, with the man-eating plants, strange storytellers, and snakes mistaken for neckties, synthesized the best of the Ceres stories with the best aspects of the Rickie Wood stories. These stranger tales will be what later muck monster creators will draw their best material from. And if the early Heap stories don't engage me as much as the later two volumes will, the sense of being there at the beginning of the story, watching the experimentation as the Heap begins to find its way, more than makes up for it. The Heap, Volume 2.

No comments:

Post a Comment