Although Man-Thing was not invented by Steve Gerber, it did attain popularity because of his brilliant and unconventional writing. So although this article will examine the early Man-Thing stories by other writers, the main thrust will be on the man who brought it to prominence. Man-Thing was originally conceived by Gerry Conway and Roy Thomas. As discussed in the Skywald Heap entry, this likely came about after the lunch Sol Brodsky and Thomas had in which Thomas suggested resurrecting the Hillman Heap. That Heap came out in March 1971, Man-Thing in May of the same year, the first Swamp Thing story in July.

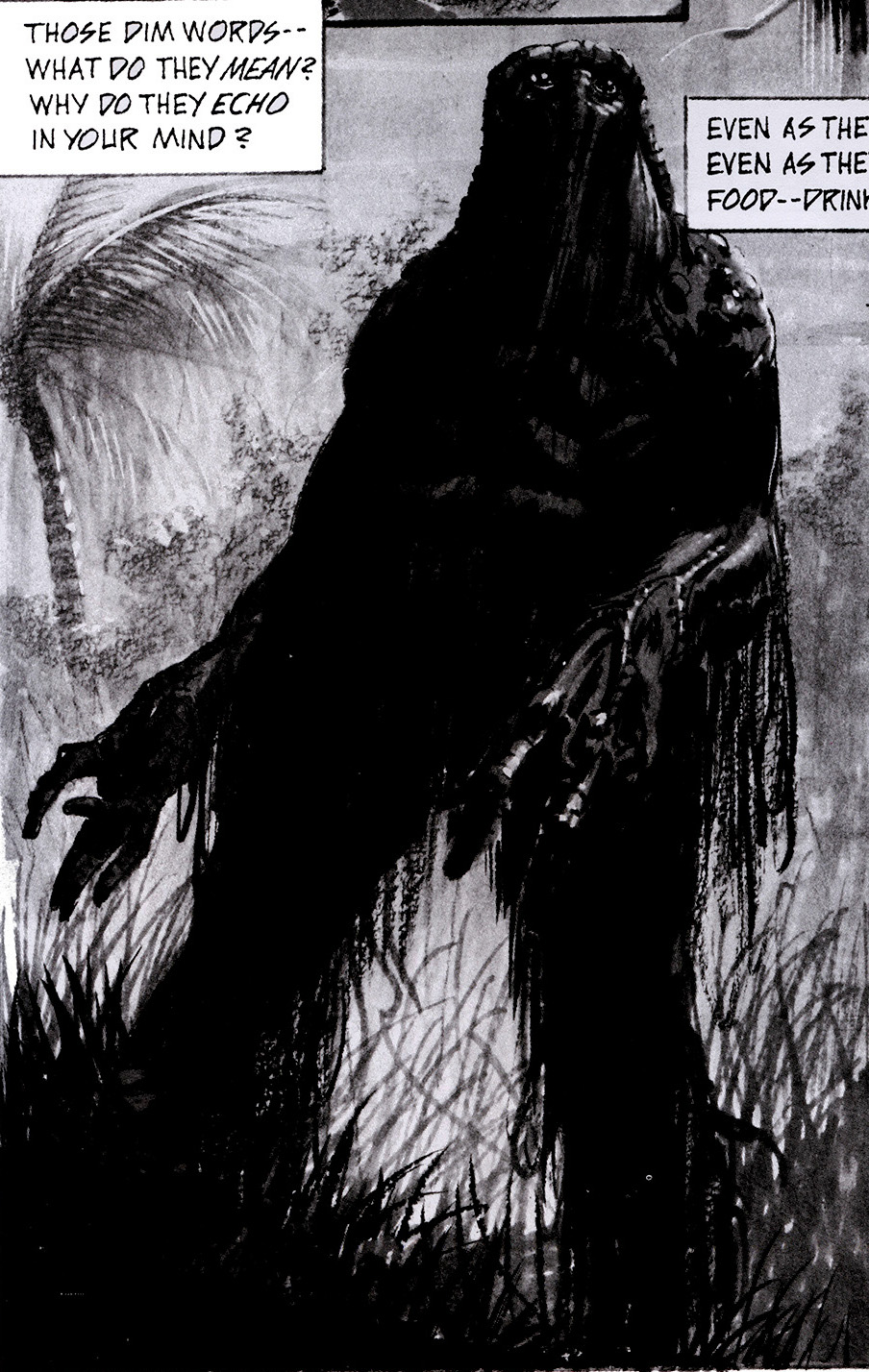

Although Man-Thing was not invented by Steve Gerber, it did attain popularity because of his brilliant and unconventional writing. So although this article will examine the early Man-Thing stories by other writers, the main thrust will be on the man who brought it to prominence. Man-Thing was originally conceived by Gerry Conway and Roy Thomas. As discussed in the Skywald Heap entry, this likely came about after the lunch Sol Brodsky and Thomas had in which Thomas suggested resurrecting the Hillman Heap. That Heap came out in March 1971, Man-Thing in May of the same year, the first Swamp Thing story in July.The initial Man-Thing story could have been taken from the pages of Skywald’s Psycho. Savage Tales 1 was a black and white magazine, thus avoiding the Comics Code Authority. Like Psycho, it had a titillation factor that would not have been acceptable in a mainstream Marvel comic. The story also has a heavy narration, setting a creepy, Gothic mood. Wonderfully atmospheric Gray Morrow art cements the tone.

Physically, Man-Thing looks the most like the Heap out of all its vegetable spawn. The Heap's distinctive carrot-nose flanked by three root-like tentacles. It changes between being shaggy and gloopy, depending on the artist involved, although it it generally described as being shaggy. Aside from that, it is huge and muscular, generally human-shaped, although sometimes the head juts out from the chest in a distinctly inhuman way.

The initial story can be seen as an origin, or as a complete and self-contained story like Sturgeon’s “It”. Scientist Ted Sallis is working on reformulating the super-soldier serum. Unable to deal with working in a government lab, he moves to an isolated lab in the Everglades. Violating security, he brings his girlfriend, Ellen. She doesn’t seem to have packed enough clothing. Ellen, it turns out, is looking for a better lifestyle, and intends to sell Sallis’s newly-developed formula. He breaks away from her thugs, and races away. To keep the formula from falling into their hands, he injects himself with it, and crashes his car into the swamp. The combination of super-soldier catalyst and the swamp turn him into the Man-Thing. Subsequently empowered, he takes his revenge on the thugs. He spares Ellen’s life, but his touch causes her to burn. Only in the last panel, with a tribute to HP Lovecraft’s “The Outsider” does Man-Thing realize he has been transformed into a grotesque.

If the origin story sounds familiar, it’s likely because it is similar to that of Swamp Thing. But it’s also very close to Roy Thomas’s Glob origin. The protagonist dies in the swamp with a chemical catalyst which does not kill but transmutes the character into an aberration. This is also the origin of many swamp creatures that come after. Sludge, Swamp-Thing, Garbage Man, and The Lurker in the Swamp all share this origin, with a few tonal variations.

Len Wein wrote a follow-up to the Savage Tales story, possibly in between his original Swamp Thing story and Swamp Thing 1, but Savage Tales was shelved until 1973. Roy Thomas, either on his own initiative or at someone else’s prompting, decided to drop the story, art and all, into an Astonishing Tales storyline involving Ka-Zar. Wein’s writing makes it clear that the Man-Thing is not sentient, but rather close to mindless. It is, however, Thomas' wrap-around story that comes up with the specific statement that the Man-Thing hates fear, that its touch burns only in response to fear. This allows Ka-Zar to interact with the Man-Thing without paying a price. At the end of the second story, like the Frankenstein creature in Bride of Frankenstein, Man-Thing pulls a lever and destroys a lab, himself in it.

It’s impossible to keep a good monster down. Only two months after its ostensible death, the Man-Thing emerges again in Fear 10, cover date October 1972, again with writer Gerry Conway, and edited by Roy Thomas. It’s a domestic issue, involving the troubles of swamp-dwelling a man and a woman, well written without any magic or super-science that is not the Man-Thing itself. Like the initial story, it could be self-contained, in case it failed. It’s a good, creepy story that again shows the versatility of the Man-Thing character and the possibilities nonstandard story structures featuring it. Like the Heap before it, stories aren't about the Man-Thing. They happen around it.

The very next issue of Fear, December, Steve Gerber begins writing. As had been established by Conway, Gerber knew to let other characters and elements carry the Man-Thing story. Things happen that the Man-Thing is not directly involved in. This requires a lot of creativity, since stories have to grow out of elements other than the character. The Man-Thing can’t even acknowledge his supporting cast. The sentient Skywald Heap had a goal: restoring itself to human form. Although Man-Thing does occasionally get returned to human form, it’s not something he pursues.

Gerber was surprisingly comfortable with the multiple genres that the Marvel universe offered. He began with a tale of occultism, a summoning gone wrong. The Man-Thing intervenes, and the devil is banished. It’s a pretty conventional story, but when Gerber gets the book firing on all cylinders, the story structures are similar to the better Heap stories. Man-Thing is not as much a character as a vehicle for justice. And Steve Gerber saw a lot of injustice in the world.

With his second issue, the second issue, Feb 1973’s “No Choice of Colors” that Gerber established that he was not going to be an ordinary comic. The Man-Thing encounters Jackson, a black man on the run from racist sheriff Corlee. Jackson claims he is being set up because he is romantically attached to a white woman, once Corlee has eyes for. When they run into Corlee, however, it turns out that Jackson murdered the deputy who came to arrest him. The two shout at each other, fervent in their hatreds. Ultimately, the Man-Thing sees no difference between them. And rather than act, he walks away. But when Corlee is murdered, there is only one source of hatred. What follows is the first full iteration of what will become the Man-Thing’s tag line: “Whatever knows fear burns at he touch of the Man-Thing.”

This is a story about very gray justice. Both men are guilty, both men hate and fear the other. The difference is that Corlee is armed, and when the Man-Thing withdraws his protection, Corlee shoots Jackson. Justice is not served. Each man is guilty, Corlee is clearly a racist of the worst stripe, and Jackson may be more justified in his loathing of Corlee, but that doesn’t justify his murder of the deputy. Both are consumed by hate, and rather than dictate a moral high ground, Gerber condemns both.

This is a story about very gray justice. Both men are guilty, both men hate and fear the other. The difference is that Corlee is armed, and when the Man-Thing withdraws his protection, Corlee shoots Jackson. Justice is not served. Each man is guilty, Corlee is clearly a racist of the worst stripe, and Jackson may be more justified in his loathing of Corlee, but that doesn’t justify his murder of the deputy. Both are consumed by hate, and rather than dictate a moral high ground, Gerber condemns both.One of the major themes that develops in Gerber’s work with Man-Thing was morality, often condemning unthinking allegiance to traditional icons (religion, parents, community) which leaves no room for mercy or compassion. Standing against these rigid icons are dissidents and loners, free-thinkers who are able to see that he traditional authorities have lost heir way, and make the mistake of speaking truth to power. The Man-Thing is the defender of such people, protecting them when they do not have the skills or resources to do so themselves. Which is not to say that every loner he wrote was the moral authority of the story. His villains include the Cult of Nihilism, and other very strange fringe groups. But

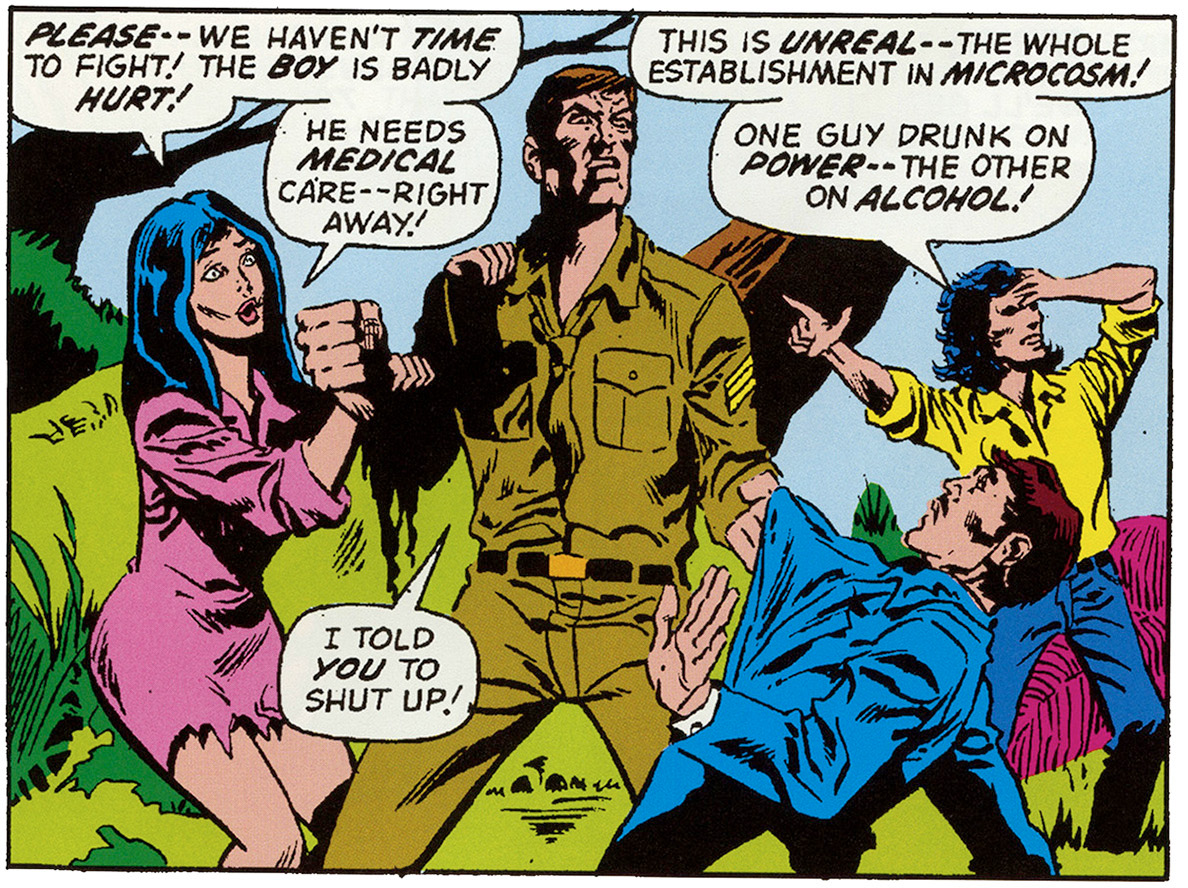

Another unusual aspect of his work is his smooth movement from genre to genre. In Fear 14, Gerber begins to mine a rich vein of Moorcockian fantasy, transporting the Man-Thing and Jennifer Kale to a strange world of wizards and gladiatorial combat. The Man-Thing’s swamp, as coincidence would have it, is the Nexus of All Realities, a weak point where it is easier to contact different planes of existence. This simple device allows Gerber to explore multiple secondary world fantasy settings. But he never settled down to explore just one of these options. After a Superman parody, Gerber wrote “Question of Survival” an entirely human-centric story in Fear 18. After a bus crash, radically different characters, a nihilist, a nurse, a soldier, and a construction foreman attempt to work together in order to get themselves, and a wounded child, to civilization. But the personalities clash, each ideology so precious that they cannot get along, even to save themselves. Only the nurse survives. And again, Gerber isn’t interested who is right, he’s interested in who is less wrong than the others.

It does, however, bring out another theme in his work. Whenever there are conflicting points of view, as there often are, generally speaking it’s the voice of business that turns out to be murderous. Overall his anti-capitalist stance is subtle. Everyone associated with the construction project are irredeemably evil. A construction worker shoots a native American in the back. Foreman Ralph Sorrell murders two men to keep his drunk driving, which killed others, a secret. Without the intervention of the Man-Thing, he would have murdered a nurse. Perhaps the most prominent businessman is the subtly-named F. A Schist, the developer with deep pockets who is planning on bulldozing part of the everglades near Citriusville in order to put in an airport. It's difficult to say if Gerber is saying that evil breeds, or at least employs similar evil, or if he wanted to tie all these villains together.

Which is not to say that industrialists were the only villains in his work. Gerber is also scornful when it comes to power. The Netherspawn speechifies about its power, but Gerber says in the narration that the Man-Thing is unimpressed, because it doesn’t understand the word. When shifty motorcycle gang leader Snake attacks the Man-Thing leaving his chain stuck in its mucky body. When it casually discards it, the chain strikes Snake in the head, possibly killing him. Ruth, a former associate of Snake’s, says that he used to call the chain his ‘power.’ “You envy my success, the wealth I’ve amassed!” says F. A. Schist in Man-Thing 8 “The Gift of Death.” “That’s why you want to destroy me!” The weird Cult of Entropy, a group of villains who pay lip service to living without illusion, but will kill anyone who lives in a way they don't approve of. Their leader, Yagzan, bears a suspicious, jowly resemblance to an aged Richard Nixon.

Which is not to say that industrialists were the only villains in his work. Gerber is also scornful when it comes to power. The Netherspawn speechifies about its power, but Gerber says in the narration that the Man-Thing is unimpressed, because it doesn’t understand the word. When shifty motorcycle gang leader Snake attacks the Man-Thing leaving his chain stuck in its mucky body. When it casually discards it, the chain strikes Snake in the head, possibly killing him. Ruth, a former associate of Snake’s, says that he used to call the chain his ‘power.’ “You envy my success, the wealth I’ve amassed!” says F. A. Schist in Man-Thing 8 “The Gift of Death.” “That’s why you want to destroy me!” The weird Cult of Entropy, a group of villains who pay lip service to living without illusion, but will kill anyone who lives in a way they don't approve of. Their leader, Yagzan, bears a suspicious, jowly resemblance to an aged Richard Nixon. Man-Thing became popular enough to warrant its own title. After Fear issue 19, Marvel put the Man-Thing in its own book, and Morbius, the Living Vampire was the headliner for Fear until it ceased with issue 31.

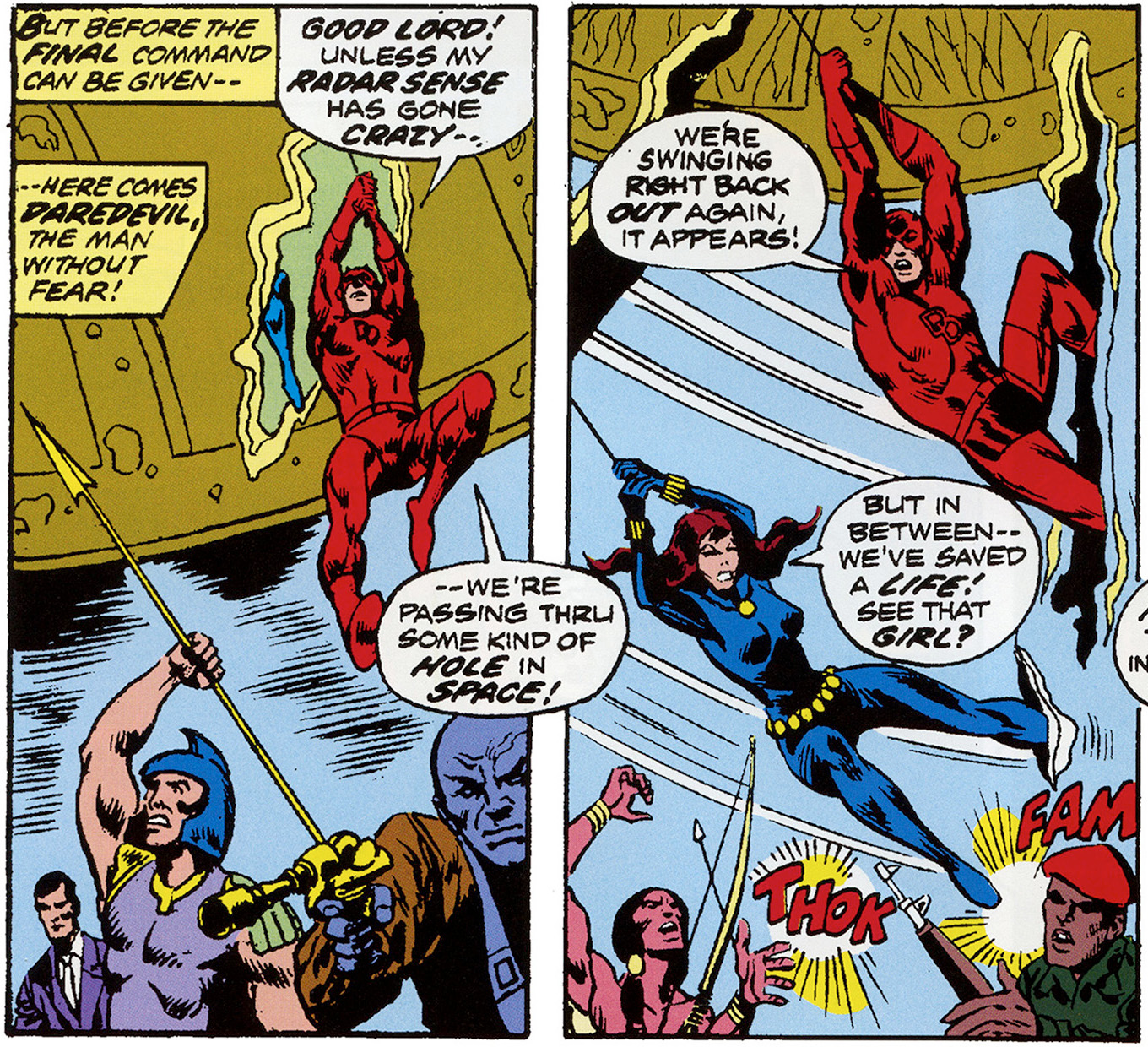

Gerber also wrote with a sly sense of humor that is tremendously appealing. In the very first issue of Man-Thing, Daredevil and Black Widow swing through a very chaotic scene. They don’t impact the story at all. But it’s quite funny to see the famous characters, who Gerber wrote, pop through in a time when most crossovers were serious affairs. Which isn’t to say that Man-Thing didn’t interact in a meaningful way with the rest of the marvel Universe. Just as Man-Thing was getting its own title, the swamp creature appeared in the Gerber-scripted Marvel Two In One 1, ‘Vengeance of the Molecule Man” in which Ben Grimm, the Thing, decides that the Man-Thing is stealing his moniker. The later team up to Molecule Man, who reverts both Thing and Man-Thing to Ben Grimm and Ted Sallis, respectively. Ultimately, the story is a clever retelling of the origin of the Man-Thing, available to those who might not have been reading Fear, and an attempt to hook in the Thing fans who might not have been aware of the Man-Thing.

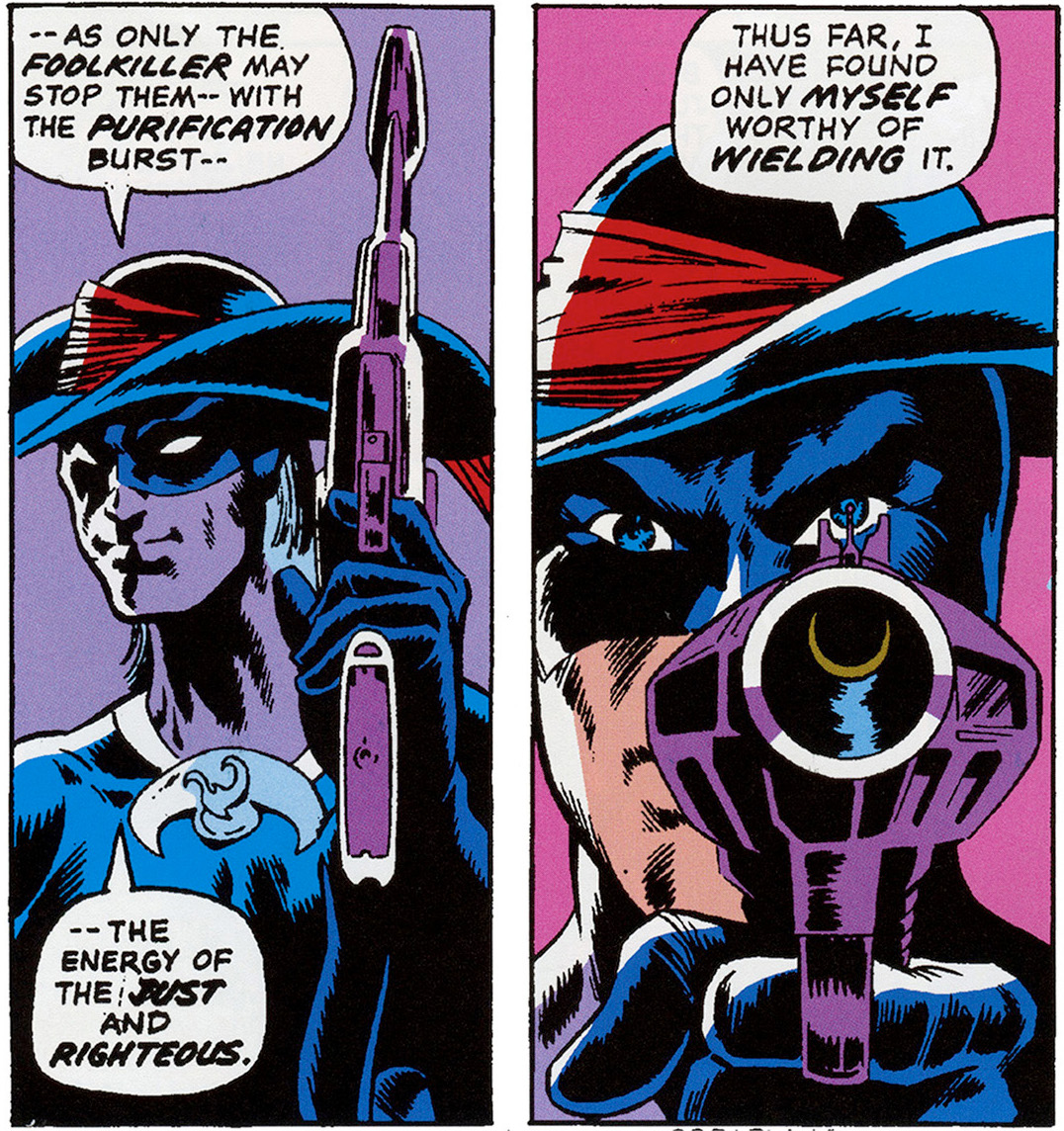

Gerber also wrote with a sly sense of humor that is tremendously appealing. In the very first issue of Man-Thing, Daredevil and Black Widow swing through a very chaotic scene. They don’t impact the story at all. But it’s quite funny to see the famous characters, who Gerber wrote, pop through in a time when most crossovers were serious affairs. Which isn’t to say that Man-Thing didn’t interact in a meaningful way with the rest of the marvel Universe. Just as Man-Thing was getting its own title, the swamp creature appeared in the Gerber-scripted Marvel Two In One 1, ‘Vengeance of the Molecule Man” in which Ben Grimm, the Thing, decides that the Man-Thing is stealing his moniker. The later team up to Molecule Man, who reverts both Thing and Man-Thing to Ben Grimm and Ted Sallis, respectively. Ultimately, the story is a clever retelling of the origin of the Man-Thing, available to those who might not have been reading Fear, and an attempt to hook in the Thing fans who might not have been aware of the Man-Thing. Gerber created many memorable characters, and trusted his creativity enough to discard them when their characters no longer fit his stories. The Foolkiller is a villain who is a parody of a superhero. Essentially the same as the Punisher, who emerged a few moths after the Foolkiller’s debut. The Foolkiller is unhinged, and and believes he knows who should live and who should die, and takes a more active hand in the process than most. He is a fanatic, and more importantly, a religious fanatic, believing he is guided by God. And although he has his targets, there are others who he doesn’t seem to mind killing. For defying him. Or merely scoffing at him. Gerber’s depiction of narcissistic megalomania is spot on, as the self-justifying Foolkiller murders victim after victim, assured of his own righteousness.

Gerber created many memorable characters, and trusted his creativity enough to discard them when their characters no longer fit his stories. The Foolkiller is a villain who is a parody of a superhero. Essentially the same as the Punisher, who emerged a few moths after the Foolkiller’s debut. The Foolkiller is unhinged, and and believes he knows who should live and who should die, and takes a more active hand in the process than most. He is a fanatic, and more importantly, a religious fanatic, believing he is guided by God. And although he has his targets, there are others who he doesn’t seem to mind killing. For defying him. Or merely scoffing at him. Gerber’s depiction of narcissistic megalomania is spot on, as the self-justifying Foolkiller murders victim after victim, assured of his own righteousness.Gerber's breakout character was Howard the Duck. A humanoid, four-foot duck who could speak, Howard was a non-superhuman character in a superheroic world, and became popular enough to warrant his own title. He started out as a refugee in the Nexus of All Realities, and never really fit into the Marvel universe. As a duck among humans, he's perpetually out of his element, constanly baffled by the intricacies and insanities of modern American culture, Howard was a way for Gerber to share his point of view with the audience. Howard's own magazine sold well, but only as long as Gerber wrote it. Others have tried, but no one has really managed to match Gerber's writing. The same holds true with Man-Thing. Other writers have written the series, but it has never proved as popular as it did in Gerber's hands. Relaunches of Man-Thing have not been successful. A 1979 relaunch didn't even last twelve issues. The next attempt didn’t even last nine. This may be the result of writers attempting to place Man-Thing into more standard, central role to which the character is not suited

Gerber’s most acclaimed Man-Thing story is probably “Night of the Laughing Dead,” a psychodrama enacted by the ghost of a clown who has just committed suicide. It is one of the best depictions of depression that I have ever run across. The ghost of Darrell, the clown, forces the mortal around him to re-enact scenes from his life. Because he is a sad clown, all of these involve the systematic destruction of his happiness. A father who neglected him favor of his financing work, an unhelpful psychiatrist, and finally, the circus owner who used him for his money. These have conspired to poison the clown’s creative well, to render him capable of fulfillment, and making his comedy a failure. Only when the aerialist admits that she loves him does his soul bound free, released from the constraints of self-doubt and the feeling of a life wasted.

Symbolically, the Man-Thing attacks one of the self-doubt demons, and I can’t help wonder if this is symbolic of Gerber’s sense of fulfillment from writing Man-Thing. Clearly, the project was personal, and at this point, he had not engaged in the lawsuit against Marvel in regards to his intellectual property. But with Gerber gone, there’s no way to verify this. Still, the portrayal of the struggling artist is a fascinating and clearly a deeply personal one, and it clearly resonated with readers. The story was popular enough that Marvel made a heavily-modified version of the story into a power record, a combination of comic book and 45 RPM record, available here.

Giant-sized Man-Thing 2 (November, 1974) involves the capture of the Man-Thing, which is interesting because Swamp Thing 14, released only a month after, also involves the capture and imprisonment of the main character.

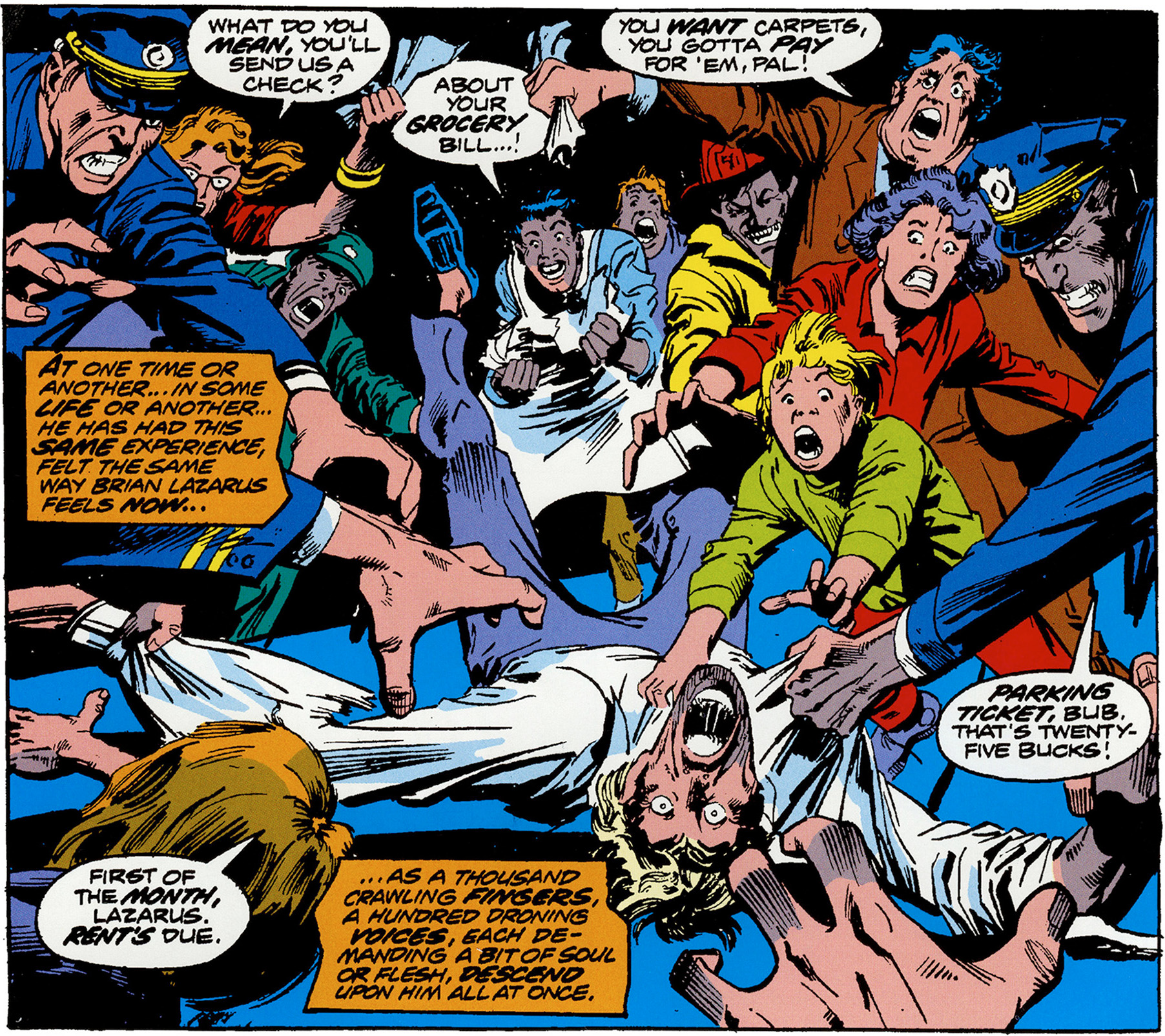

Man-Thing 12 contains another one of Gerber’s unconventional stories. “Song-Cry of The Living Dead Man.” In some ways similar to “Night of the Laughing Dead” a writer has come to an abandoned asylum in order to write in peace, but his fears and daily turmoil pursue him, in a real rather than a metaphorical way. Again, the monsters are defeated when someone tells the writer Brian that she loves him. This piece, so clearly personal to Gerber, would be followed up in 2012, four years after Gerber’s death, with the Infernal Man-Thing miniseries.

Again demonstrating his versatility, Man-Thing next encounters a ship of pirates, commanded by Captain Fate. Now, Skywald’s Heap had also encountered pirates, after stowing away on board a cargo ship, in issue 11, March of 1973, nearly two years before. Coincidence? Was Steve Gerber reading Psycho magazine, or was there something that both writers had read or seen that made them think classic Caribbean pirates would be a good antagonist for their swamp creature? But where the Psycho pirates turn out to be inspired by 18th century pirates, Gerber’s story instead involves a hundred year-old pact, reincarnation, a floating tower, and a sympathetic satyr. It may not have been his best story, but it certainly wasn’t a predictable one.

Again demonstrating his versatility, Man-Thing next encounters a ship of pirates, commanded by Captain Fate. Now, Skywald’s Heap had also encountered pirates, after stowing away on board a cargo ship, in issue 11, March of 1973, nearly two years before. Coincidence? Was Steve Gerber reading Psycho magazine, or was there something that both writers had read or seen that made them think classic Caribbean pirates would be a good antagonist for their swamp creature? But where the Psycho pirates turn out to be inspired by 18th century pirates, Gerber’s story instead involves a hundred year-old pact, reincarnation, a floating tower, and a sympathetic satyr. It may not have been his best story, but it certainly wasn’t a predictable one.Man-Thing 15, "A Candle for Saint Cloud" is daring in that the Man-Thing doesn’t technically appear in it at all. Instead, we have a candle (and a fair amount of urban fantasy) of the Man0Thing, which causes all who breathe its fumes to dream of the Man-Thing. But the story, a love triangle with perky blonde hippy Sainte-Cloud as the hypotenuse. She purchases a candle of the Man-Thing, and its theoretically-drugged wick provokes visions of the Man-Thing. In the vision, shared by Sainte-Cloud and her blind boyfriend, is disrupted when her other suitor kicks down the door. Fortunately, the drug is potent, and the vision Man-Thing stops the violence before anyone who doesn’t deserve it gets hurt. This stands a bit opposed to some of Gerber’s previous endings, for example, “No Choice of Colors” where he doesn’t allow the virtuous to triumph, but allows the tragedy to unspool. Again, Gerber has radically shifted gears, with a story of a flying pirate ship one month, and a small, domestic, human story the next.

"Decay Meets the Mad Viking” in Man-Thing 16 again touches on some of Gerber’s favorite subjects. The establishment gone mad and inhuman. Josefsen is strong and able at sixty-five, and considers that men who are not strong are all weak, hippies, and wussies. Compared to his own remarkable self, of course. His loathing of weakness extends to far that he chases Astrid, his granddaughter, into the Man-Thing’s swamp, swinging a battle axe, screaming that she’s a traitor. He destroys the encampment of a nihilistic rock star, who had set up shop where Sallis was murdered, seeking inspiration from tragedy. Gerber writes some of his most truly nihilistic words in the end of the episode: "Then, the last traces of hope must be wiped out. The jaded young pale into insignificance while something unsoiled endures. Only the mad must be left to inherit the Earth.”

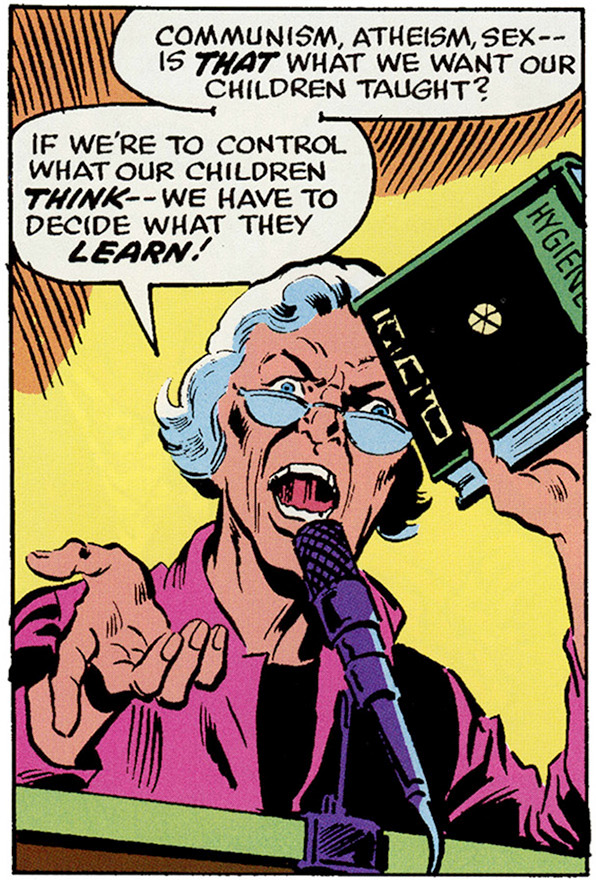

"Decay Meets the Mad Viking” in Man-Thing 16 again touches on some of Gerber’s favorite subjects. The establishment gone mad and inhuman. Josefsen is strong and able at sixty-five, and considers that men who are not strong are all weak, hippies, and wussies. Compared to his own remarkable self, of course. His loathing of weakness extends to far that he chases Astrid, his granddaughter, into the Man-Thing’s swamp, swinging a battle axe, screaming that she’s a traitor. He destroys the encampment of a nihilistic rock star, who had set up shop where Sallis was murdered, seeking inspiration from tragedy. Gerber writes some of his most truly nihilistic words in the end of the episode: "Then, the last traces of hope must be wiped out. The jaded young pale into insignificance while something unsoiled endures. Only the mad must be left to inherit the Earth.” Gerber's stories could be daringly topical, also. He tackled high school suicide in Giant Sized Man-Thing 4, a controversial topic, but not one specifically banned by the Comics Code Authority, It is strange reading the comic so many years later and realizing how long it has taken for phrases like ‘fat-shaming’ and ‘toxic masculinity’ to come into our culture. He also takes on a moral panic, with a woman standing on the public stage waving a book about sexual hygiene screaming “Communism, atheism, sex – is that what we want out children taught? If we’re to control what out children think – we have to decide what they learn!” How little America has changed since 1974. I will also note that there is no supernatural ignition for the panic. Humanity cannot dodge responsibility, the villainy presented are all too human.

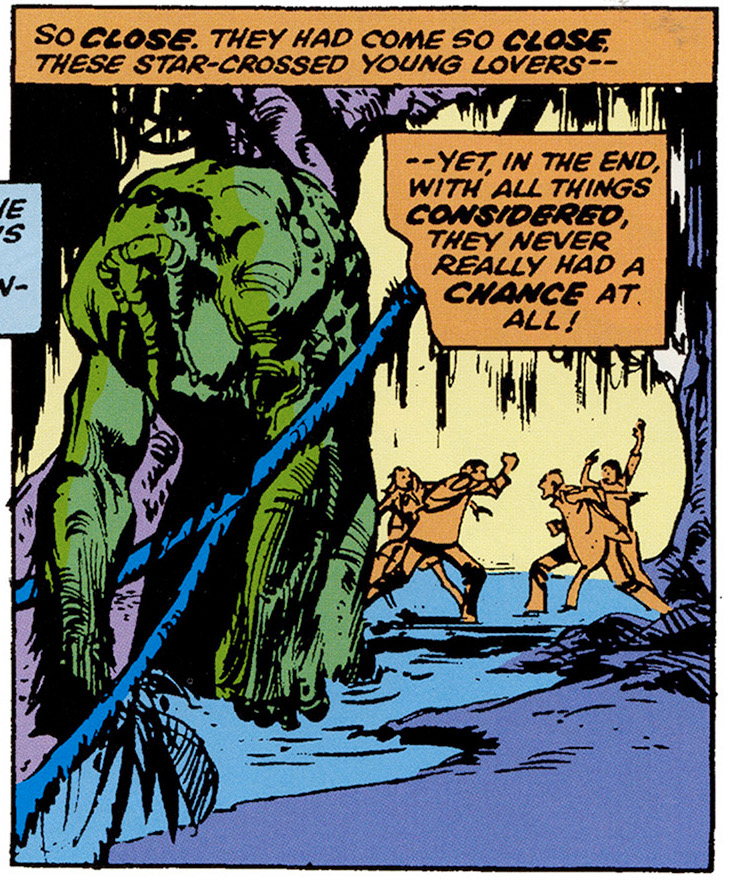

Gerber's stories could be daringly topical, also. He tackled high school suicide in Giant Sized Man-Thing 4, a controversial topic, but not one specifically banned by the Comics Code Authority, It is strange reading the comic so many years later and realizing how long it has taken for phrases like ‘fat-shaming’ and ‘toxic masculinity’ to come into our culture. He also takes on a moral panic, with a woman standing on the public stage waving a book about sexual hygiene screaming “Communism, atheism, sex – is that what we want out children taught? If we’re to control what out children think – we have to decide what they learn!” How little America has changed since 1974. I will also note that there is no supernatural ignition for the panic. Humanity cannot dodge responsibility, the villainy presented are all too human. Giant-Sized Man-Thing 5 brought a new story from Gerber, but also a new editor at Marvel, Len Wein. Wein took over from fellow Swamp Monster scribe Roy Thomas in issue 15. Wein’s story is rich with language, as are all his Swamp Thing stories. Wein had finished with Swamp Thing at the end of 1974, and took over editing Man-thing pretty quickly, starting with the March 1975 issue of Man-Thing. Wein had clearly picked up a thing or two from Man-Thing. His short Romeo and Juliet story concerns two kids in love despite their parents’ antagonism, both to each other and the romance. The parents (their fathers, truth be told) were business partners, but they ended up angry at each other, and literally come to blows once they find their children, who have run off into the swamp. The only thing that stops their fighting is when their daughter begins sinking into quicksand. Unable to rescue her, and even Man-Thing cannot, they watch helplessly as she drowns. Her boyfriend then shoots himself, and we end up with a perfectly Romeo and Juliet ending. But the last frame makes it clear that this does not spell the end of the parents’ argument.

All things must come to an end. With sales dwindling, the decision was made to close down the Man-Thing book with issue 22. But Gerber knew that this was the end, and was able to write one of the most unusual endings to a comic.

All things must come to an end. With sales dwindling, the decision was made to close down the Man-Thing book with issue 22. But Gerber knew that this was the end, and was able to write one of the most unusual endings to a comic."Pop Goes the Cosmos" takes place at the end of a superhero plot involving mind-control, as well as the fantasy characters he had created. But the issue is framed as a letter from Steve Gerber to Len Wein, his editor. Illustrated, as Gerber and Wein are now parts of the story. Dakimh, the mage introduced in the fantasy issue Fear14, has been telling Gerber the stories Gerber has been writing as comics. In a delightfully weird piece of metafiction that was at least thirty years before its time, Gerber stands back and writes the climax of his Man-Thing series with heavy narration, as if it were a confession letter to his editor, including himself in the narrative. "Pop Goes the Cosmos" is one of the weirdest, and at the same time the best sendoffs any comics has received. And it is yet another unexpected story from Gerber, who still had tricks up his sleeve after writing Man-Thing and Giant-Sized Man-Thing as well as various other comics, for four years.

But as with many personal projects, Gerber would return to write Man-Thing after he departed the book. Man-Thing would pop up in Gerber's Howard the Duck book on occasion. He also wrote a Man-Thing story in the black and white Rampaging Hulk 7 in 1978. Again, the story is a throwback to the Skywald and Warren magazines. Man-Thing encounters a wild woman, Andrea, who wears a home-made bikini that seems on constant danger of falling off. Titillation factor achieved. The story is another one of Gerber's interesting psycvhodramas, with exterior factors acting in concert with Andrea's inner division.

Gerber will show up a few more times as I move the timeline forward. Most notably, he had an indelible impact on the future of the Man-Thing, but he also wrote Sludge, a mucky character with a similar origin for Malibu comics during the early 90’s indie explosion. Most poignantly, he also left behind his final Man-Thing script, which later became the Infernal Man-Thing. And, of course, other writers used the Man-Thing in their stories, with some degree of success. The Man-Thing showed up in a lot of books, from Thor to the Micronauts, Strange Tales, She-Hulk, X-Men, Ghost Rider, Punisher, Deadpool, and even reformed villain book Thunderbolts. Gerber's legacy of the flexibility of the character lives on.

Gerber will show up a few more times as I move the timeline forward. Most notably, he had an indelible impact on the future of the Man-Thing, but he also wrote Sludge, a mucky character with a similar origin for Malibu comics during the early 90’s indie explosion. Most poignantly, he also left behind his final Man-Thing script, which later became the Infernal Man-Thing. And, of course, other writers used the Man-Thing in their stories, with some degree of success. The Man-Thing showed up in a lot of books, from Thor to the Micronauts, Strange Tales, She-Hulk, X-Men, Ghost Rider, Punisher, Deadpool, and even reformed villain book Thunderbolts. Gerber's legacy of the flexibility of the character lives on.Gerber demonstrated that like the Heap, Man-Thing as a nonthinking swamp monster character was viable, and in the correct hands, an almost infinitely plastic concept. Man-Thing worked well in superhero comics, stand-alone weird tales, as well as a vehicle for character exploration. His time on Man-Thing serves to demonstrate how versatile he was as a writer, and how adaptable the concept of the swamp man is. Where Swamp Thing under Wein stuck to Gothic horror and weird tales tropes, Man-Thing leapt from fantasy to quiet horror to domestic drama. And they remain interesting and poignant reads today. Particularly trenchant is Gerber’s use of the moral panic in issue Man-Thing 17 and 18, and his treatment of teen suicide. These remain relevant some forty years after he wrote them. As always, comic stories vary in quality, but the Gerber Man-Thing remains consistently good at its lowest, and stellar when he’s making social observations. More than almost any other comic writer, Gerber made his Man-Thing stories personal. His stories took on the issues he saw in the world, and with enough skill that they entertained. A common failing of didactic entertainment is that it emphasizes the didactic and fails to be entertaining. Although Gerber shows us villains and heroes, he does not make his stories black and white morality tales. They may not be particularly subtle, but Gerber’s writing makes them entertaining, and seldom end in the easily-anticipated way. All of Gerber’s work on Man-Thing, by turns acerbic, funny, horrifying, and touching, shows a man struggling to express himself or go mad.

All images used in this article are copyright by Marvel Comics.

Special shout-out to Brian Keene. He told me to go back and re-read the Gerber Man-Thing after I had dismissed it. You were right, Brian. This stuff is amazing.

2 comments:

It's awfully good to share a love for these obscure stories with anyone.

I also wrote about the story in Iron Man Annual #3 http://ceaseill.blogspot.com/2010/10/swamp-of-indomitable-will_9.html

Around that time, I also write a bit about Ruth Hart, as a most atypical and realistic character- not a 'comic book woman' or heroine.

The word 'meme' had a more elastic meaning ten years ago, but the concept links to one blogger's notion of all of Gerber's work as one hyper-novel. Plok wrote very cerebral and quirky pieces.

Thanks for tying in some aspects about the Heap, whose Skywald stories I've not read. Usually the reference is fleeting. I'd no idea they shared some similar escapades and more characteristics.

I was brought here because the news reminded me of Josefson. There was a man I've seen elsewhere rioting at the Capitol today. He seems very much like a Gerber character.

I bought a Foolkiller issue - three- and the ghostly clown stories in Fair/ good condition as reader copies, because I thought they'd be great in their original form, especially beat-up like a copy I might find by accident behind someone's furniture or something.

Finally, I agree that was one astounding story about bullying, a common topic now with valuable vocabulary.

Are his Defenders or Howard or even Omega stories, better? Well, it's really hard to compare: I love blueberries, oranges, apples, peaches, strawberries. They each come with their own adjacent mess. But it's a chore to try to introduce the concept and talk about the stories with anyone not initiated. Too bad!

Post a Comment