Eerie was a Warren Publications magazine, which, in the seventies, was clinging to the format EC had been forced out of. Their flagship publications included Creepy, Famous Monsters of Filmland, and Vampriella. In format, Eerie is similar to Skywald’s mood-horror, a black and white magazine that avoided the Comics Code Authority’s censorius eye.

Eerie was a Warren Publications magazine, which, in the seventies, was clinging to the format EC had been forced out of. Their flagship publications included Creepy, Famous Monsters of Filmland, and Vampriella. In format, Eerie is similar to Skywald’s mood-horror, a black and white magazine that avoided the Comics Code Authority’s censorius eye.The majority of the magazine was short, moody stories, often with a buxom woman to add a little sex appeal to the story. The initial Marvin story "One is the Lonliest Number" written by Allen Milgrom, primarily known as an artist, achieving great success with Marvel's Secret Wars II and two years on The Avengers. Esteban Maroto provides beautiful line work. With this frankly stellar combination of artist and writer, the Marvin story is affectingly tragic.

Marvin merited the front cover of Eerie #49 (July 1973) Swamp Thing was in full swing, and had just published issue #5. Man-Thing was still appearing in Adventure Into Fear, but by the beginning of 1974, would be in its own magazine. The Skywald Heap had just had its final story in Psycho 13 (July 1973). So the ground was well-tread, but Milgrom managed to put the familiar tropes into a unique story.

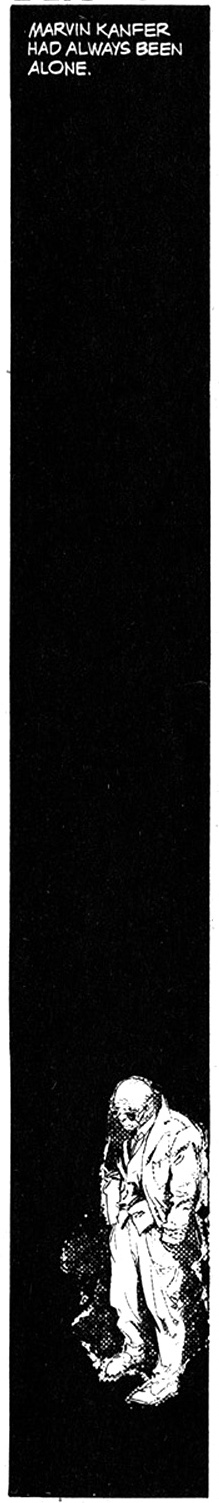

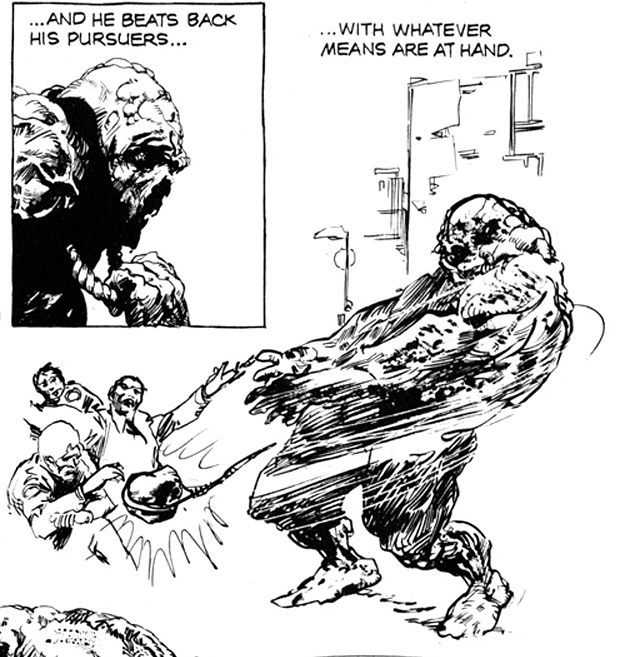

Marvin the Dead Thing is in many ways a distillation of the Swamp Monster trope. Marvin Kanfer, we are told in the first panel, had always been alone. Six panels later, he kills himself by throwing himself in a polluted river. The pollution from ‘several factories’ serves as the catalyst (like Ted Sallis’s Super Soldier Serum, Dr. Holland’s bio-restorative formula, or the executed babies in the Heap’s Wausau Swamp). The results, inevitable. Marvin returns as a swamp monster without knowing it (similar to Sallis in his first Man-Thing story). The police get involved, and Marvin gets to demonstrate his strength and his invulnerability to bullets. He is more sentient than the Man-Thing, but thought is slow, so he id not as in control of his mind as the Swamp Thing or Skywald Heap are.

Marvin the Dead Thing is in many ways a distillation of the Swamp Monster trope. Marvin Kanfer, we are told in the first panel, had always been alone. Six panels later, he kills himself by throwing himself in a polluted river. The pollution from ‘several factories’ serves as the catalyst (like Ted Sallis’s Super Soldier Serum, Dr. Holland’s bio-restorative formula, or the executed babies in the Heap’s Wausau Swamp). The results, inevitable. Marvin returns as a swamp monster without knowing it (similar to Sallis in his first Man-Thing story). The police get involved, and Marvin gets to demonstrate his strength and his invulnerability to bullets. He is more sentient than the Man-Thing, but thought is slow, so he id not as in control of his mind as the Swamp Thing or Skywald Heap are. This is the first time that the genre has mined the idea of family for the swamp monster. Previously, the monster had been a lonely presence without attachments, only friends and enemies. The transformation into the swamp monster got rid of the individual’s previous life. However, Marvin is a different sort of person. In a story that perhaps draws from the classic 1931 James Whale Frankenstein, Marvin is befriended by a young girl who is not put off by the way he looks. But a mob (literally, a torch-waving mob) comes into the swamp to hunt Marvin down. Instead of killing him, however, they kill little Susie. Unwilling to accept the death of the little girl who had been his playmate, Marvin places her body in the same toxic sludge that brought about his transformation. After weeks of waiting, he is rewarded with her sludgy resurrection. The two then bond, and presumably, live happily ever after as man and child, free of the restraints of society. The story is similar to a Morto do Pantono story, “A Pequena Silvia”.

This is the first time that the genre has mined the idea of family for the swamp monster. Previously, the monster had been a lonely presence without attachments, only friends and enemies. The transformation into the swamp monster got rid of the individual’s previous life. However, Marvin is a different sort of person. In a story that perhaps draws from the classic 1931 James Whale Frankenstein, Marvin is befriended by a young girl who is not put off by the way he looks. But a mob (literally, a torch-waving mob) comes into the swamp to hunt Marvin down. Instead of killing him, however, they kill little Susie. Unwilling to accept the death of the little girl who had been his playmate, Marvin places her body in the same toxic sludge that brought about his transformation. After weeks of waiting, he is rewarded with her sludgy resurrection. The two then bond, and presumably, live happily ever after as man and child, free of the restraints of society. The story is similar to a Morto do Pantono story, “A Pequena Silvia”.There us a bit of metaphor to be drawn from the stone and rope that Marvin uses to drown himself. If we view this as a symbol of the weight of society’s opinion which weighs on Marvin, it is this that eventually drags him down. During his conflict with the police, Marvin pulls the stone and rope off, throws it as a weapon, or sign of defiance, then he is free of society's opinions and rules. He can return to the swamp and be what he is. There’s a happy naturalness in this story. Marvin is the living rejection of modern society, and once he is free of those bonds, he can finally find satisfaction. Society is so damaged that the transformation of Marvin from human into a swamp monster is what allows him to be happy.

Esteban Maroto’s work is never more poignant as the image of Marvin holding his playmate in his arms. The despair and sadness on Marvin’s disfigured face is palpable, and really makes the point of the story.

Esteban Maroto’s work is never more poignant as the image of Marvin holding his playmate in his arms. The despair and sadness on Marvin’s disfigured face is palpable, and really makes the point of the story.Just under a decade later, in February 1982, literally the month that Wes Cravern's Swamp Thing film his the theaters, Eerie resurrected Marvin. The writer is different, and so is the artist, but this is the second Swamp Creature's resurrection . Perhaps, like the return of Swamp Thing, this return was prompted by the Wes Craven Swamp Thing film. But Marvin returned.

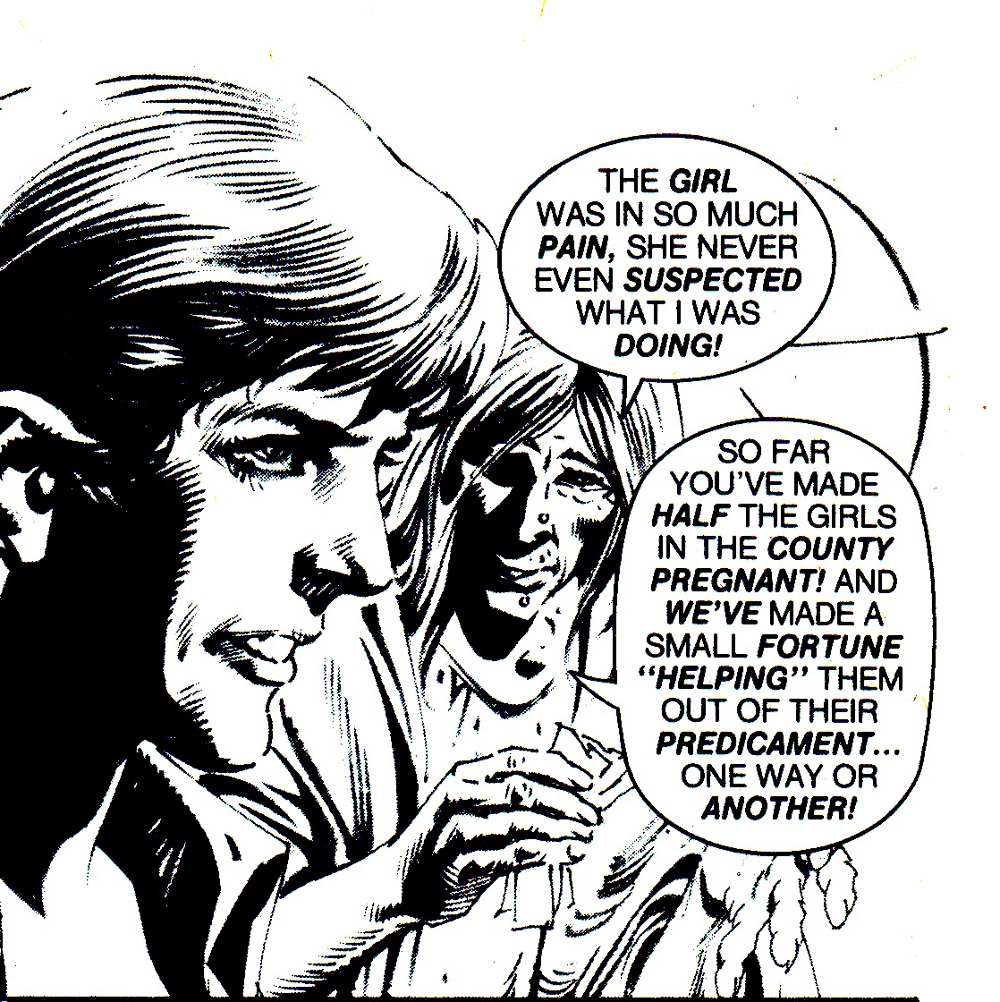

This story is less straightforward. Marvin watches a young couple dump their stillborn baby into the polluted waters that transformed Marvin into the swamp creature he is. Bobby-Jean and Billy are a troubled couple. Billy said he’d marry Bobby-Jean, but he most take care of his grandmother. But Billy is apparently a serial impregnator, and his supposedly sick grandmother is someone who takes care of unplanned pregnancies. The two of them have a business together, him taking advantage of inexperienced girls, his grandmother getting paid well to deal with the pregnancies.

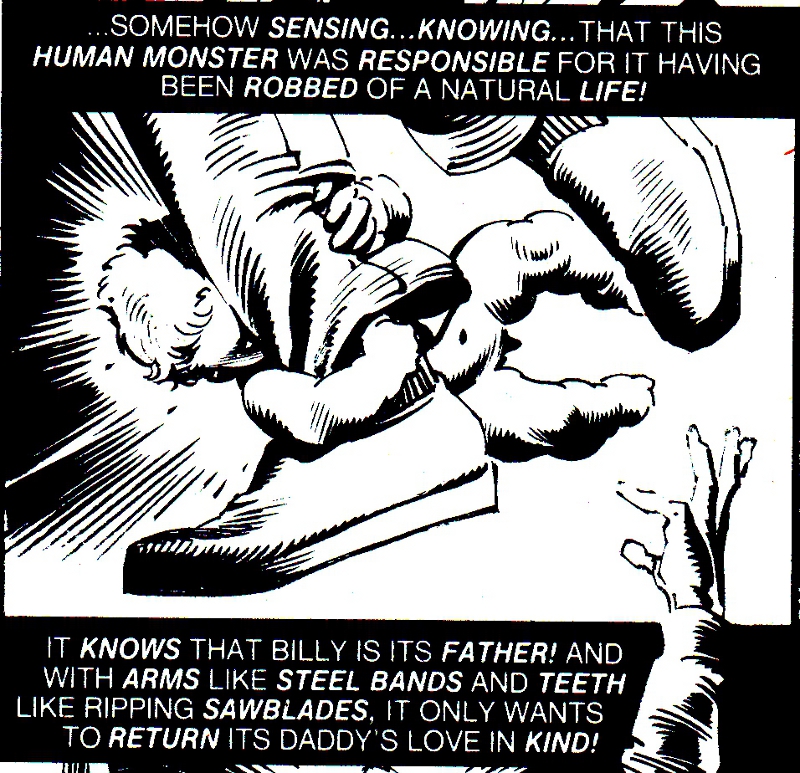

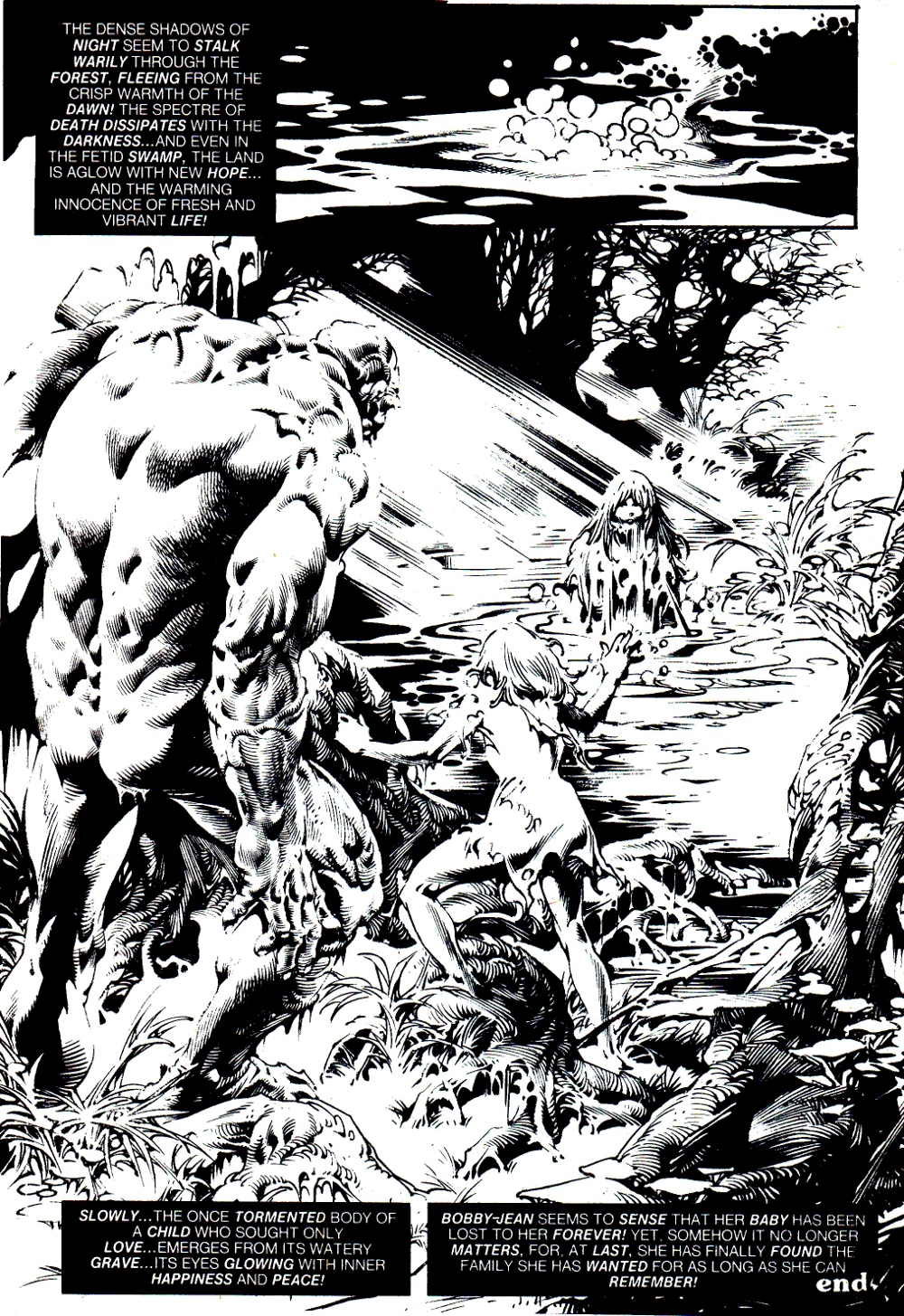

This story is less straightforward. Marvin watches a young couple dump their stillborn baby into the polluted waters that transformed Marvin into the swamp creature he is. Bobby-Jean and Billy are a troubled couple. Billy said he’d marry Bobby-Jean, but he most take care of his grandmother. But Billy is apparently a serial impregnator, and his supposedly sick grandmother is someone who takes care of unplanned pregnancies. The two of them have a business together, him taking advantage of inexperienced girls, his grandmother getting paid well to deal with the pregnancies. The stillborn babe returns to life, thanks to the polluted waters, and immediately goes out to seek its father. Bobbie-Jean, hemmorhaging, tries to escape into the swamp, and the baby finds Billy, killing him. It also kills his grandmother. Bobby-Jean, dying, is taken by Marvin to the swamp, and the three of them turn into a kind of happy swampy family.

The stillborn babe returns to life, thanks to the polluted waters, and immediately goes out to seek its father. Bobbie-Jean, hemmorhaging, tries to escape into the swamp, and the baby finds Billy, killing him. It also kills his grandmother. Bobby-Jean, dying, is taken by Marvin to the swamp, and the three of them turn into a kind of happy swampy family.There’s a whole lot more dialog and exposition in this story. And at the same time, it’s less atmospheric and less complex. This is a more straightforward murder and revenge story, and Marvin as a character plays almost no part in it. Instead, he is primarily a watcher of the action, only There are several moments when the writer uses the shortcut of a character ‘just knowing’ something that helps move the narrative along. “Ode to a Dead Thing” is not as well-written as the original story, but it does have its tender moments, such as when Marvin carries the dying Bobby-Jean into the swamps. It is a pretty straight riff on the original story, adding another member to Marvin’s family.

The themes of the original story are gone. Marvin’s rejection of the modern world has vanished, and been replaced by an evil family, Billy and his grandmother, who are selfish, irredeemable villains. They are villains who the reader will not mourn when they are murdered by the resurrected baby. Marvin’s story is more of a wrapper around the standard revenge story, with the resurrected swamp baby serving the usual Heap role of dispenser of justice.

“One is the Loneliest Number” The first Marvin the Dead-Thing story stands as an excellent encapsulation of the majority of the tropes that make the he swamp-monster work. Using the inherent loneliness of the character to good effect, as well as the pathos evoked by that character desperately, finally caring for someone else. This emotional work is muted in the second, more simplistic story, as mentioned above. I wonder if Marvin’s return was a test balloon for making him an ongoing character, If so, it did not catch on. Like Carlton’s “Lurker in the Swamp” there are only two Marvin the Living Dead Thing stories. They are worth seeking out for the swamp monster enthusiast, especially Eerie # 49.

Next Month, the end of DC's initial series of Swamp Thing, featuring writers David Michelinie and Gerry Conway.