I don't normally include dragons as kaiju. Dragons are a known quanity, and have very different themes that kaiju. Kaiju were created for film, and are presented there best. Kaiju films, after running out of science fiction trappings, have turned to more fantastic elements. Godzilla, Mothra King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All Out Attack recasts Godzilla not as a freak result of the nuclear testing, but as the physical embodiment of the rage of the dead returned to punish Japan. The Gamera series toys with Muvian superscience which is indistinguishable from magic. Pulgasari was animated through the will and suffering of good people. But here, we're dealing with straight-up fantasy elements intruding on the modern world. But dragons aren't kaiju, and neither are giant whatevers, which is why I'm including neither Reign of Fire nor Big Ass Spider.

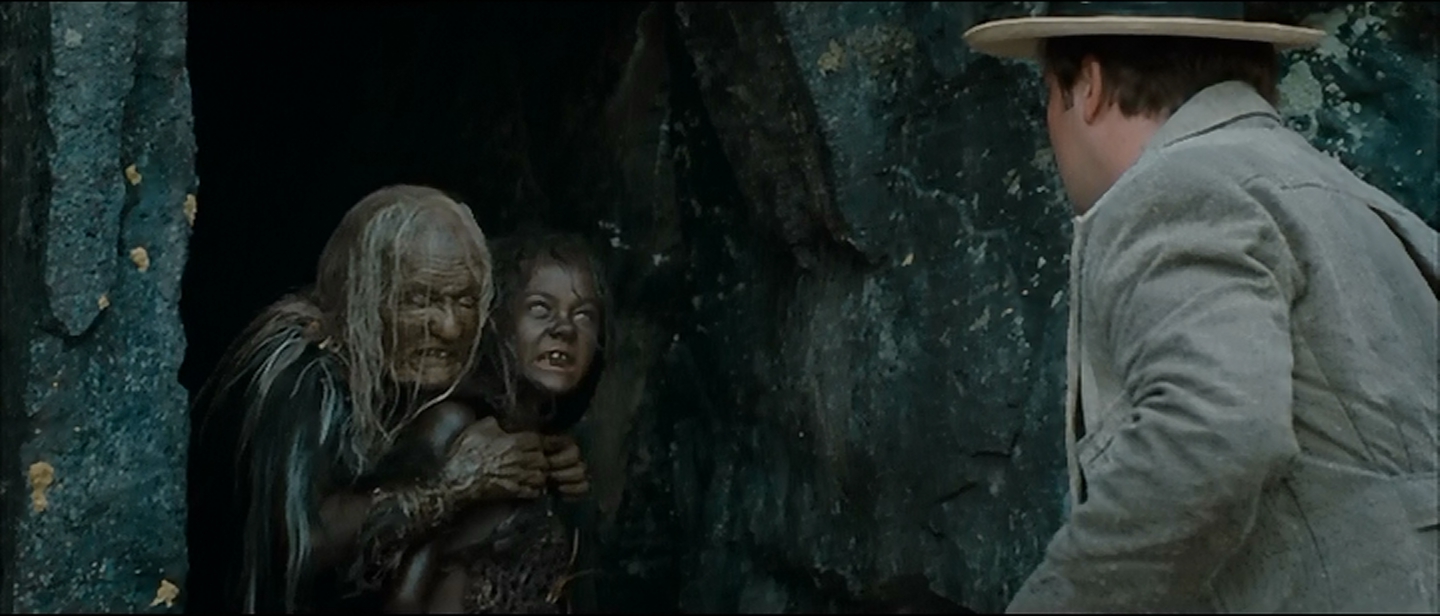

Unfortunately, Dragon Wars takes just about every fantasy cliche you could come up with in a minute. Ancient Prophecy? Check. Luke Skywalker who was really just born to be awesome? Check. Romeo and Juliet reincarnated into the Destny Couple? Check. Suspiciously Nazgûl-like evil overlord who lives in a dark brooding castle just a plane-shift away? Check. Magical Mystical talisman? Check. Evil overlord with a massive army against the forces of good who supply just two dudes? Check. Creepy prophetic dreams? Check.

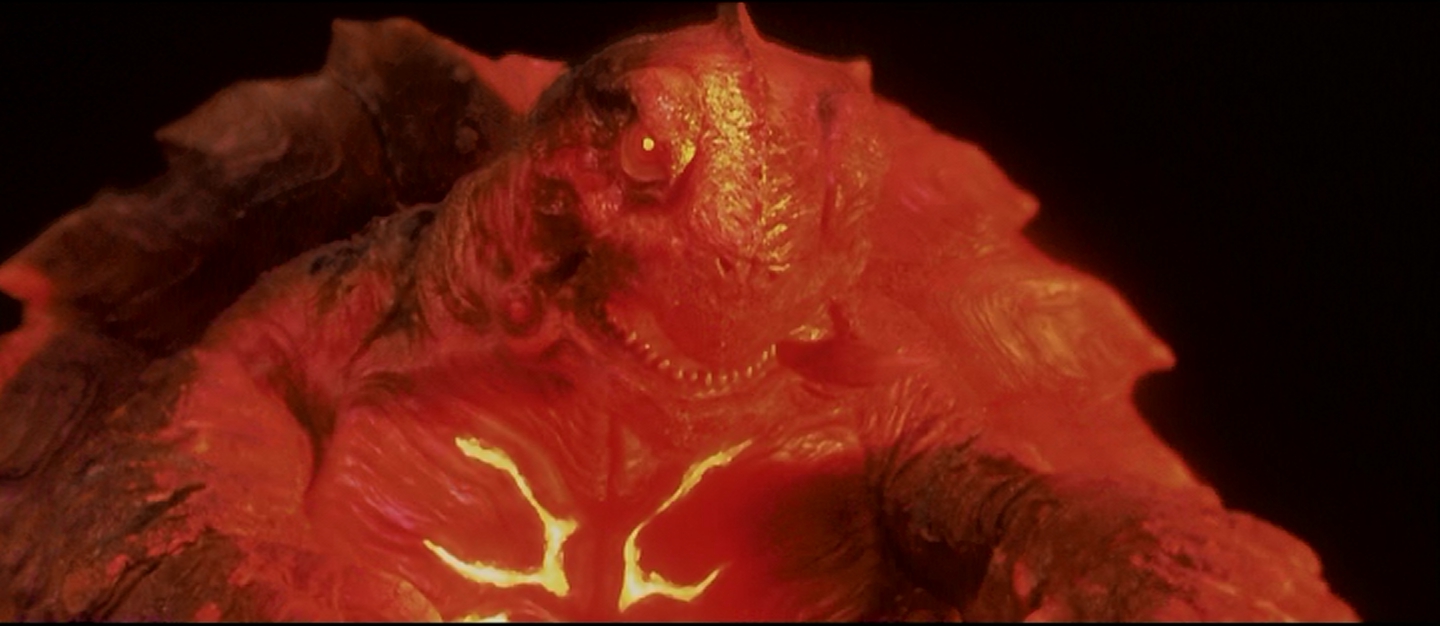

The fated girl is the carrier of the Yuy Yi Joo, (Korean for MacGuffin) and she must give up her life in order to let the Imoogi tranform into a celestial dragon. So heaven's kind of a dick, here, and women are mere incubators for power which they cannot use themselves. Way to make me like your film, Shim.

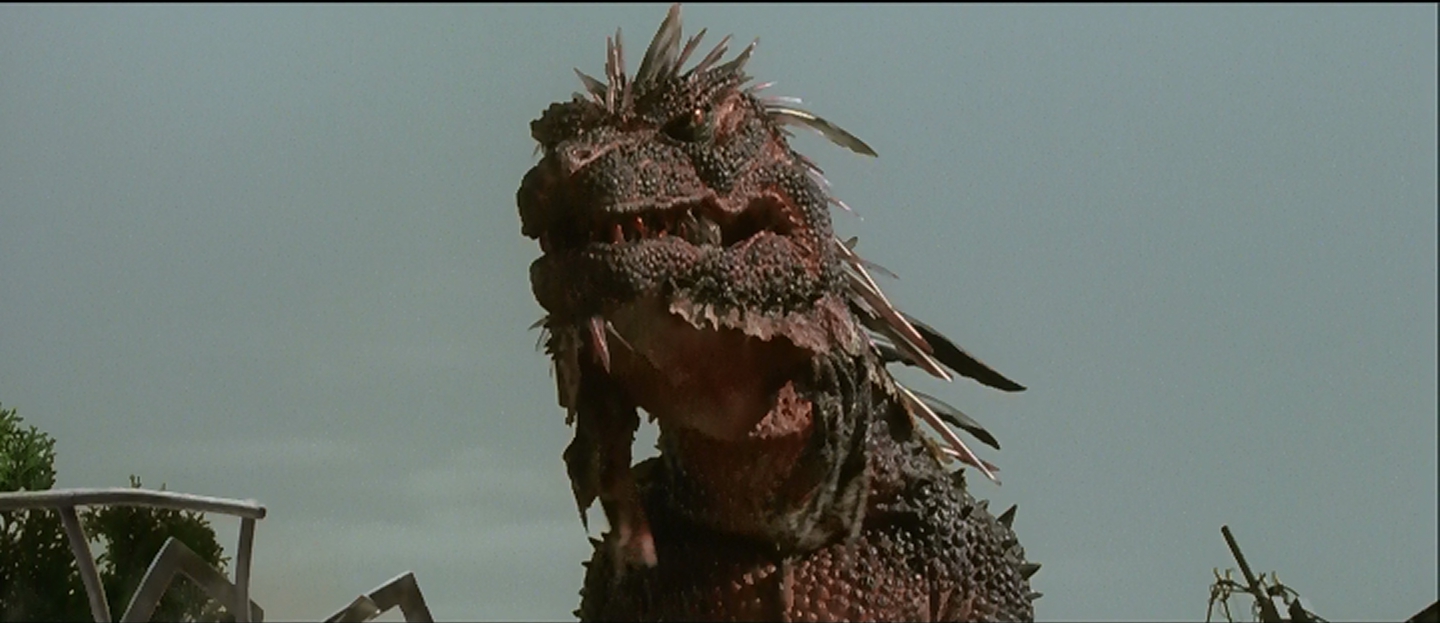

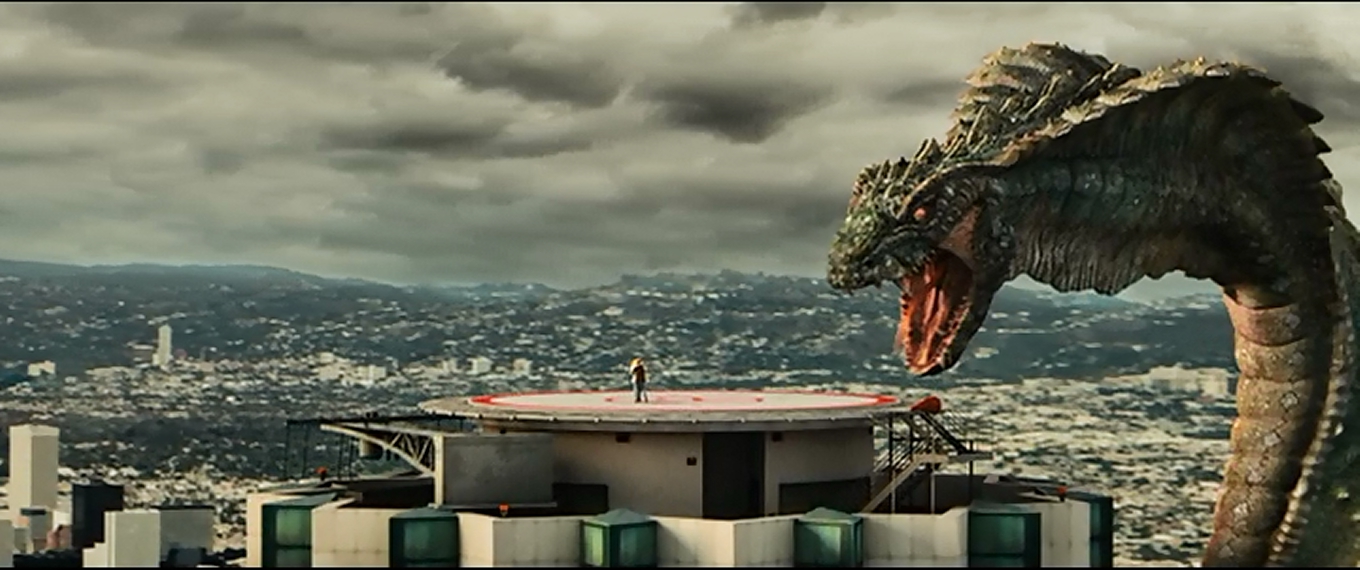

Unfortunately, the film follows some of the same beats as Yonggary. The military gets involved, and although it's not quite as embarrassing as men with jetpacks and lasers, the board meetings are similar, with infighting and disbelief among the senior government officials. There are paralells to both 1998 Godzilla and Q the Winged Serpent in that the evil Imoogi, once unleashed, periodically vanishes. Given that its head is the size of house, I have no idea how you could possibly lose track of it.

Like Gamera vs The Legion, the Imoogi has help in the form os a swarm of smaller creatures. When the Imoogi is having trouble with attack helicopters, the smaller troops fly in and swarm them. Sadly, this is what causes the majority of the damage to Los Angeles: the military and the Army of Darkness. Which has explosives that can take out a modern tank in a single shot.

Again similar to 1998 Godzilla, a trope that goes as far back as King Kong: the evil Imoogi has climbed the Library Tower in Los Angeles, and the military gets some attack helicopters into the action. Of course, the snake can lunge far enough to take out the copters, because what's the point of standing off evern a hundred yeards where the snake can't strike? Which is again part of the problem with the film. It seems like a lot of the scenes were staged because they're cool or lead to explosions.

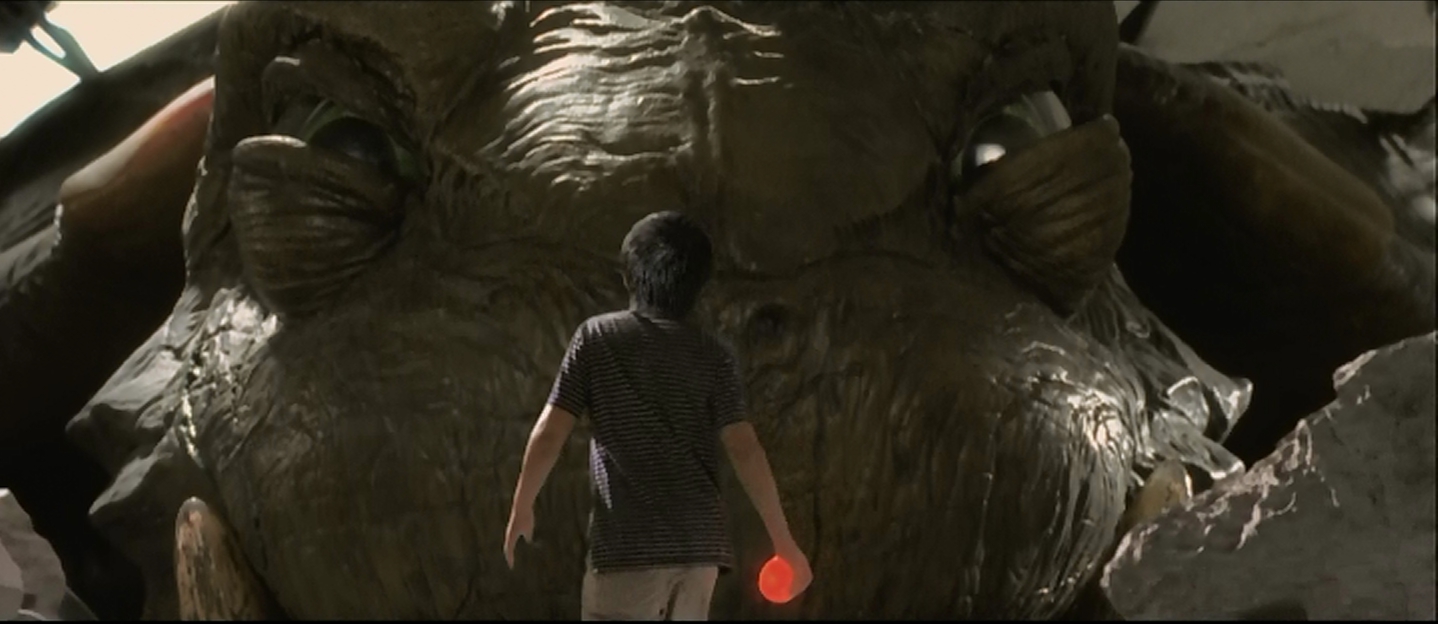

After being knocked out, our bland hero is tied to a post in front of Bara-Dur, and his medallion activates. This destroys the Army of Darkness and knocks the Imoogi senseless. Did he do anything? No, it was the medallion. Heroic agency of zero. He might as well have just given them to her, and accompanied the Big Evil to the sacrifice. Why couldn't the medallion have activated when the Army of Darkness was trashing LA?

Left face to face with the Imoogi, he is saved by... the Good Imoogi. The two snakes fight, and the girl sacrifices herself. Meaning our hero has done nothing, and hasn't even come back with the girl. The Good Imoogi becomes a dragon, trashes the bad one, and all our protagonist did was witness what happened. Of course, she didn't to a heck of a lot, either.

The end echoes Elliott and Rossio's Godzilla script: The Celestial Dragon breathes fire, which goes down Bad Imoogi's throat. Handled better in thew 2014 Godzilla, but many things were. The Celestial Dragon then runs off, leaving our protagonist in the barren planes before the broken towers of Bara Dur. How's he going to get home?

Ultimately, Dragon Wars is a hollow experience. There's not a lot of meat, and the monster destruction scenes are surprisingly uninteresting. They're quickly cut, and there isn't a sense that any of it really matters. It doesn't help that the main characters feel flat and do nothing other than watching the plot unfold. The CG is generally good, but as with the many action films, I am unmoved if I don't care about the characters or the plot. It was apparently not my destiny to care if these kids get eaten a gigantic snake or not.

Hyung-rae Shim states in the extras that this is his dream film. It made a fair amount of money, and he is shooting the sequel this year, so we can expect to see Dragon Wars 2 out sometime. Let's hope he's learned more than he did between 1999 and 2007.