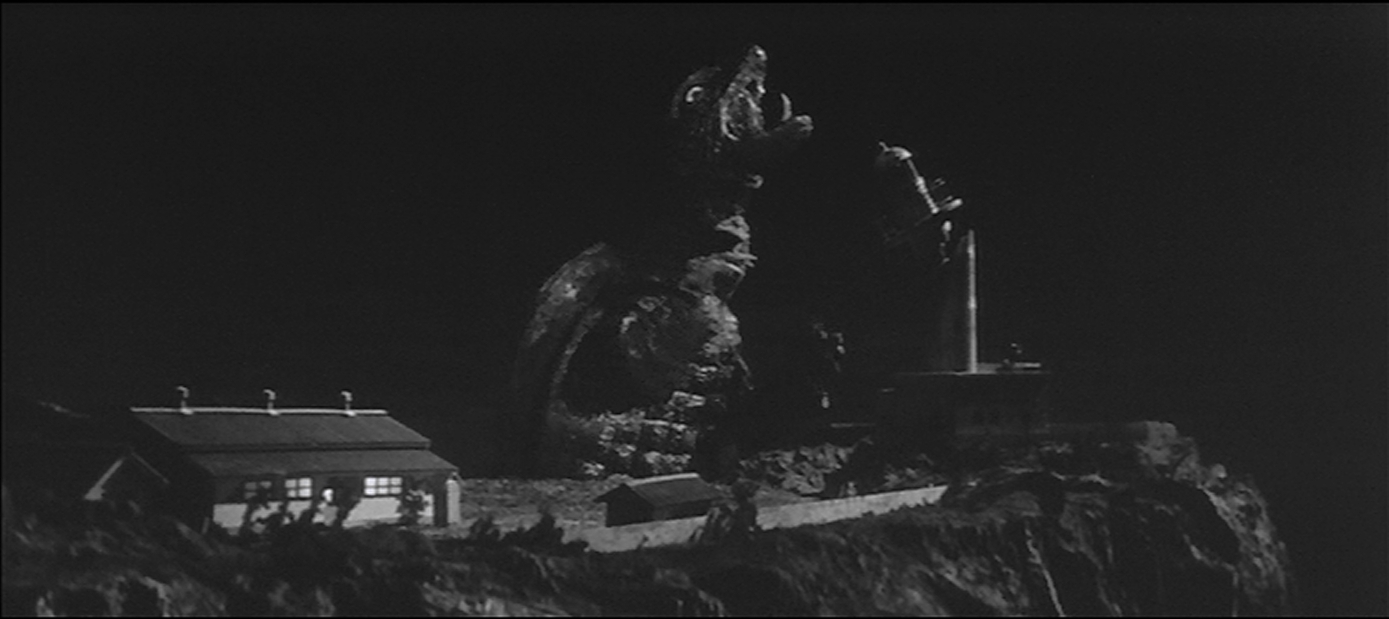

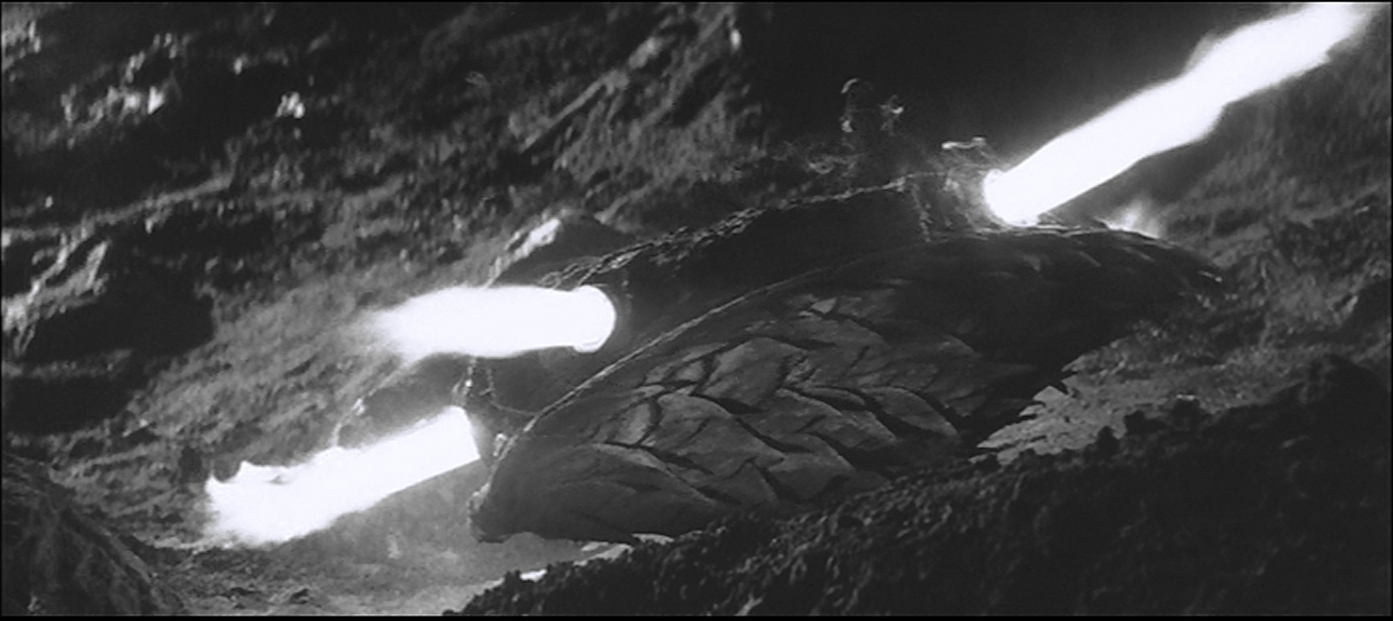

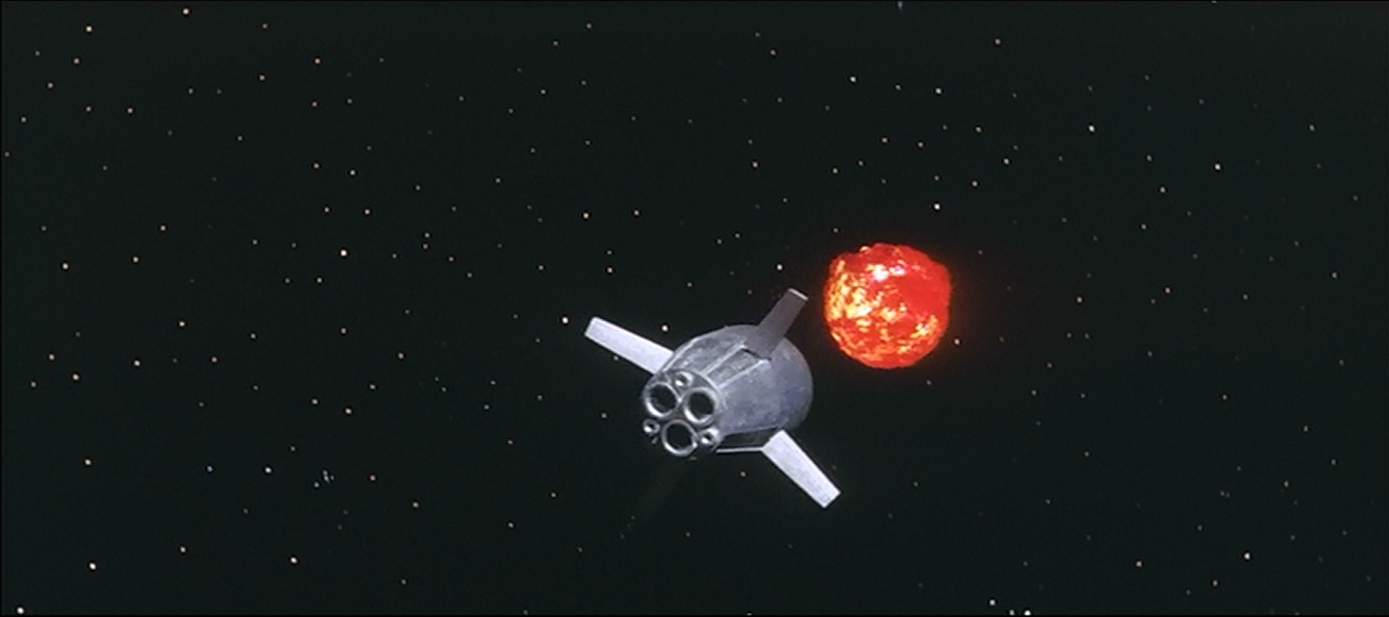

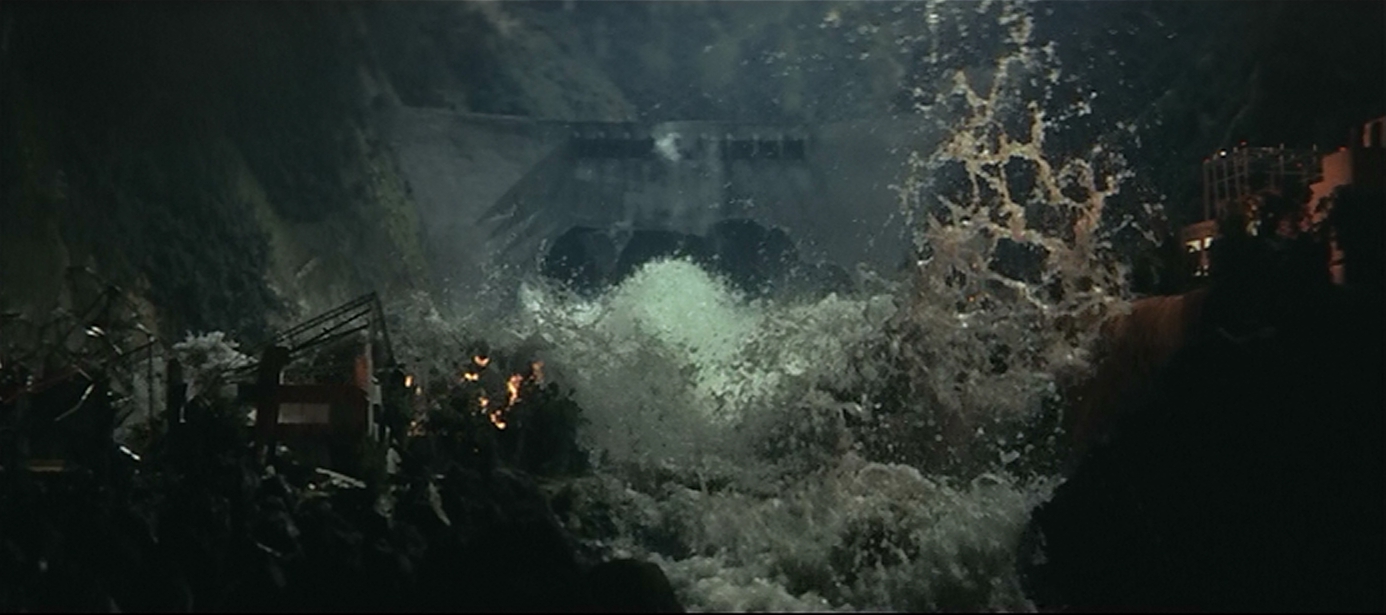

After Gamera's rocket encounters a meteor and is smashed apart, the gigantic turtle returns to Japan, the Kurobe Dam specifically. The Kurobe Dam was also featured in Ghidorah the Three Headed Monster, although where Ghidorah only features a visit to the dam, Gamera takes a opportunity to trash it.

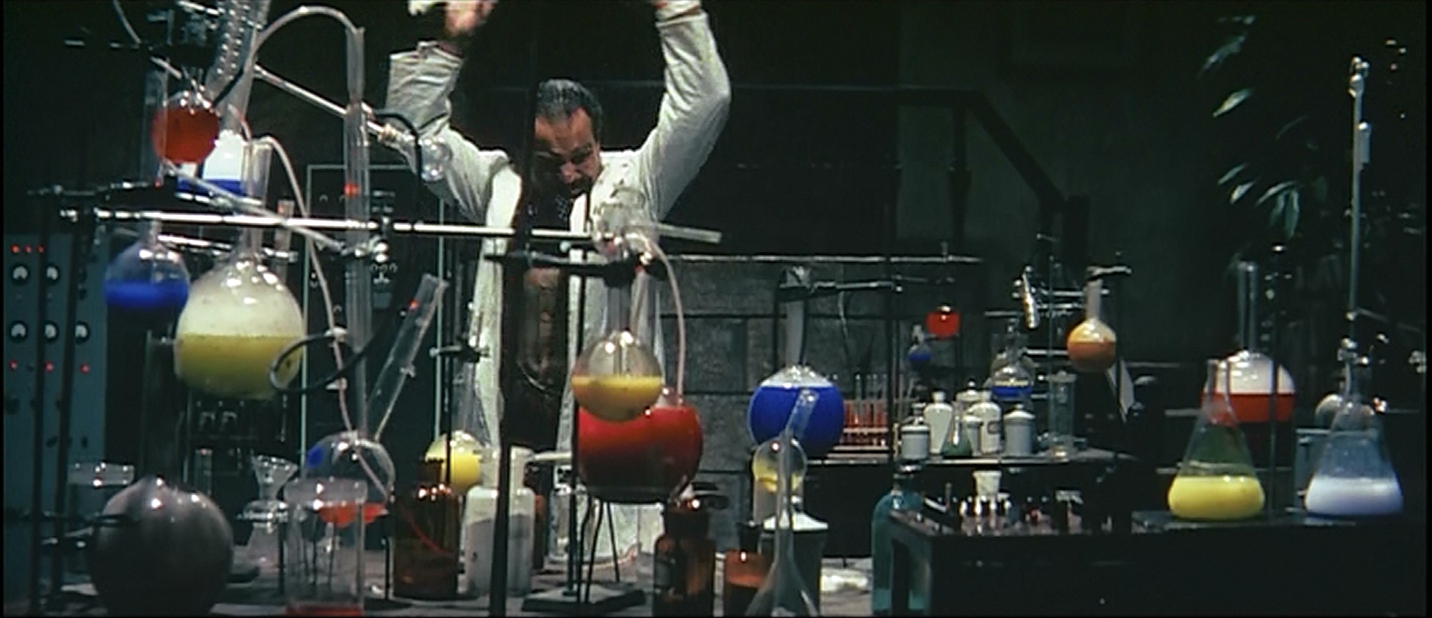

The action then shifts to the human characters. We have a plot to recover a gigantic opal from New Guinea. The 1966 interpretation of New Guinea is not particularly convincing, with the dancers in plastic grass skirts and waving pom-poms, but the dancers themselves are quite good. Our female protagonist, the chief's daughter, is of course lighter than the rest of her people, and can speak excellent Japanese.

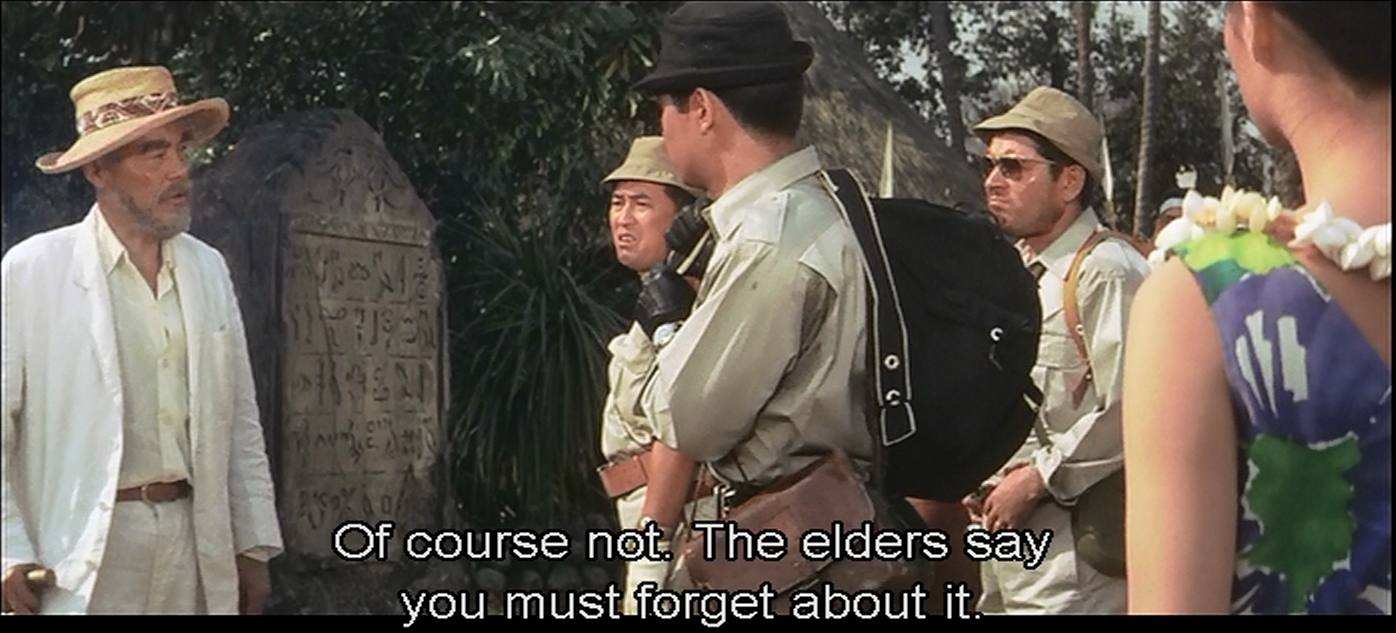

In keeping with with the 'ancient civilizations that have left warnings against giant monsters' trope begun in Giant Monster Gamera, the New Guinea village has a monolith carved with that looks to be some Egyptian hieroglyphs. This ancient piece of wisdom, possibly left by the same Atlanteans who carves the stone from Gamera, warns of the danger of Barugon.

The plot starts with four associates seeking a fist-sized opal once glimpsed in New Guinea. The main mover of the plot is a character named Onodera, who is an enormous jackass. A relentless double-crosser, he deceives at every possible moment, which leads to a lot of the human plot's tension. He beats a man with his own crutch, and breaks a chair over the the man's wife. It's difficult to think of a more despicable person in film, let alone in giant monster film, which is riddled with unethical characters. This makes his end, stuck to Barugon's tongue and devoured, quite satisfying and memorable.

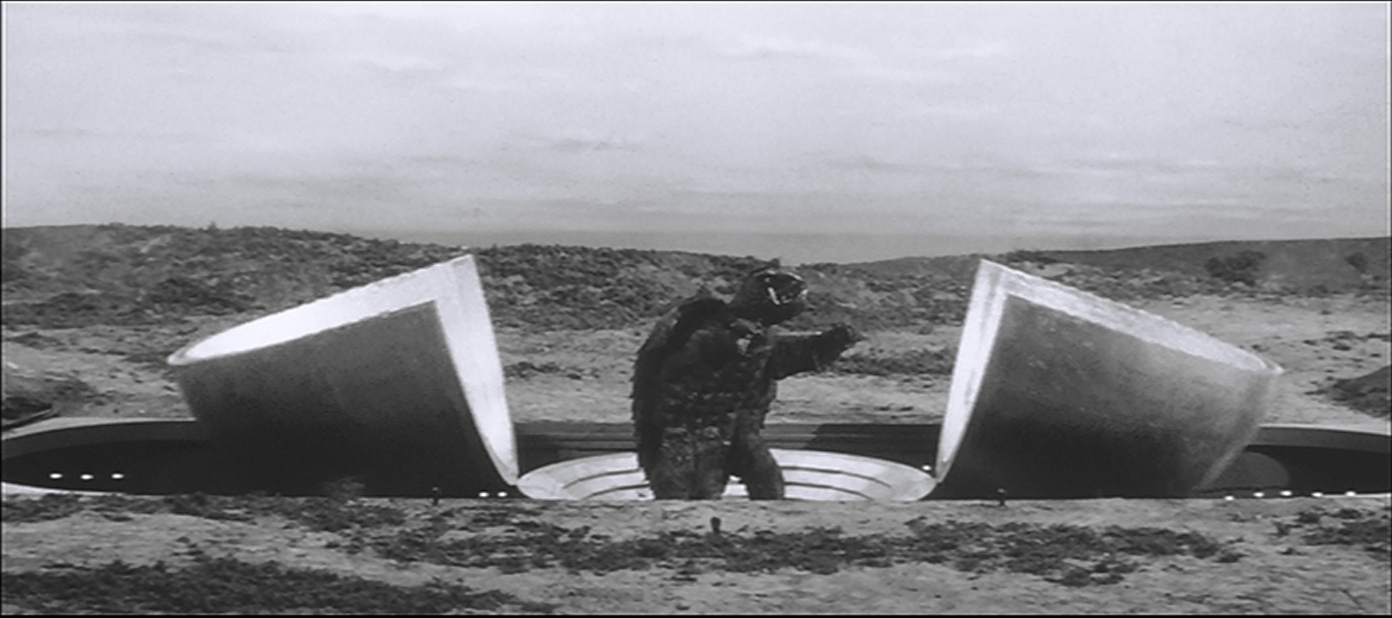

The opal is in fact the Barugon egg which, exposed to sufficient heat, hatches. Barugon seems to come from a line of monsters, rather than being a single aberration. But the background of the monster is not important. Its role is to show up, destroy stuff, and fight the other monster.

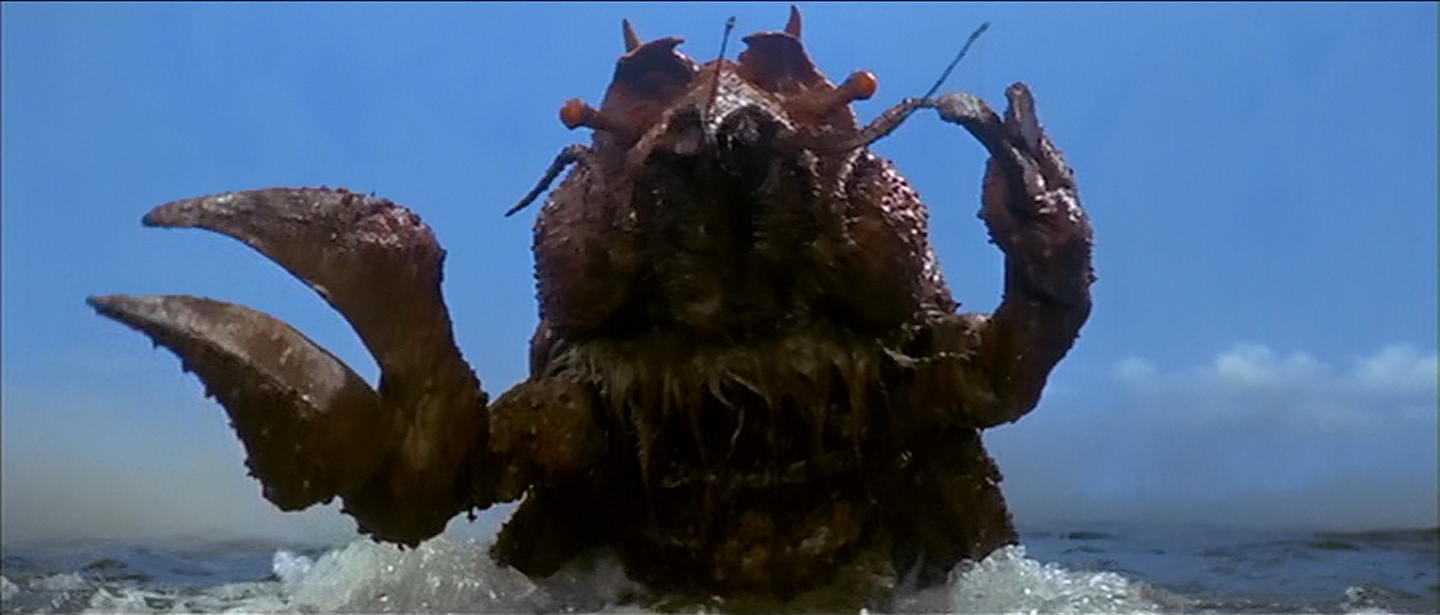

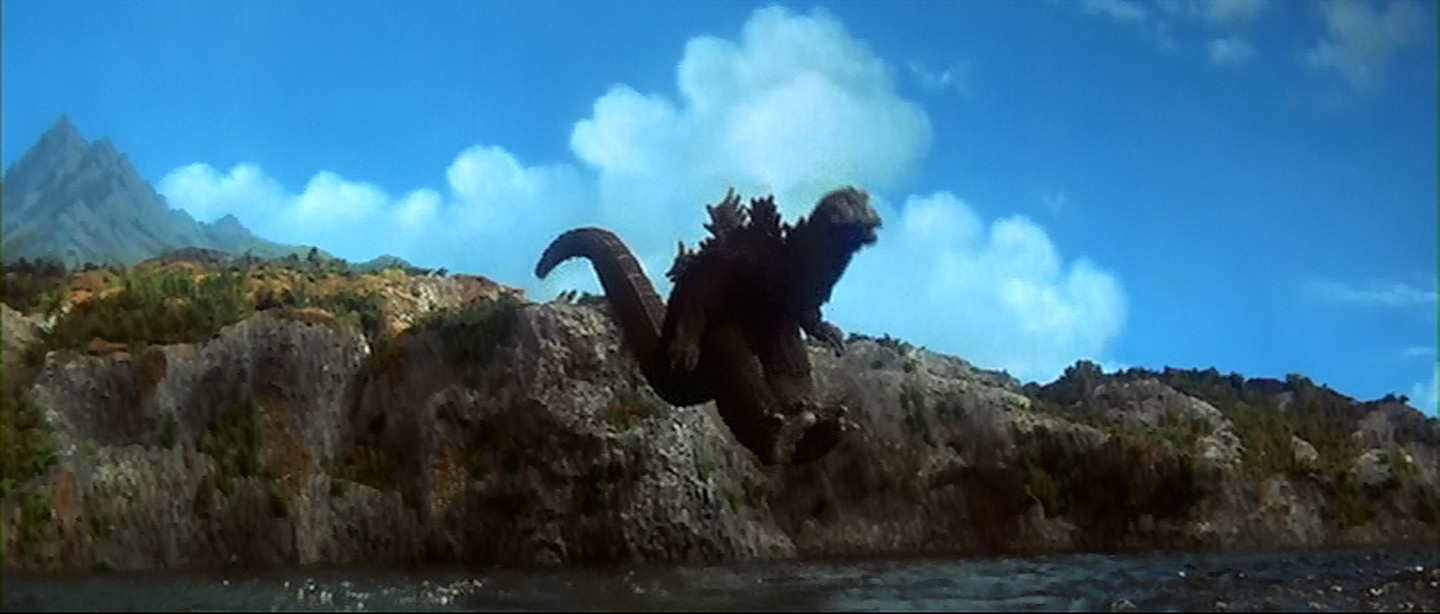

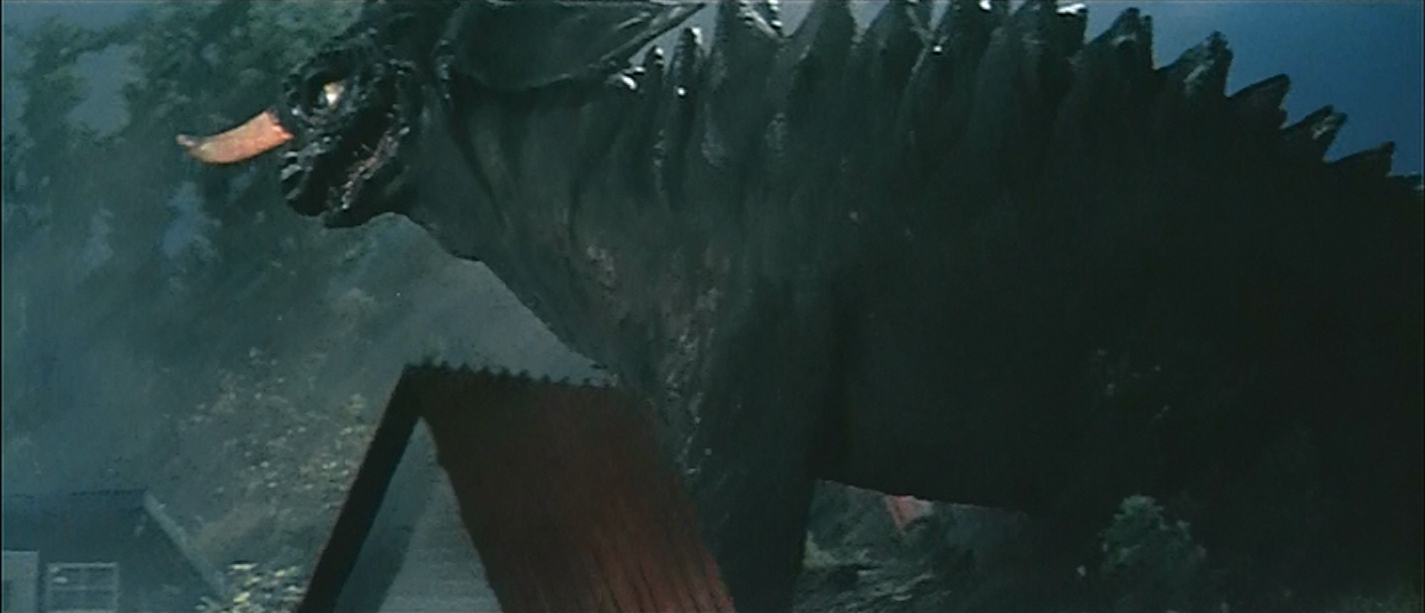

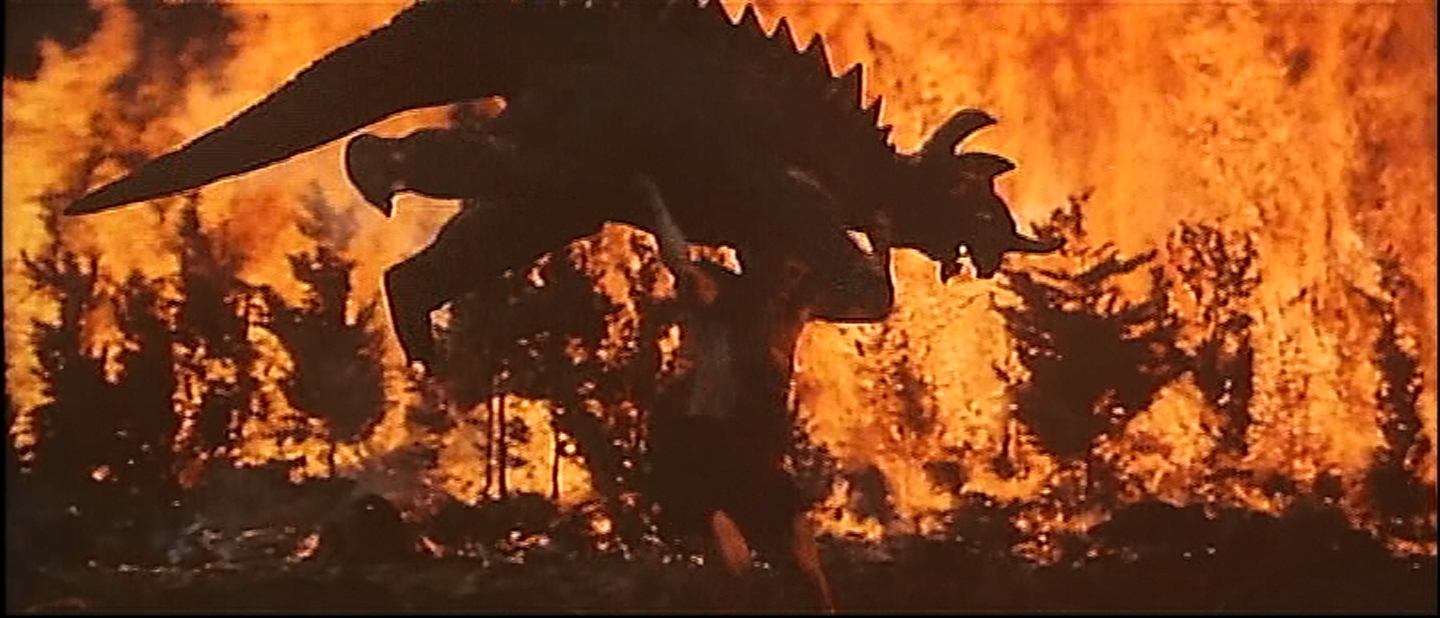

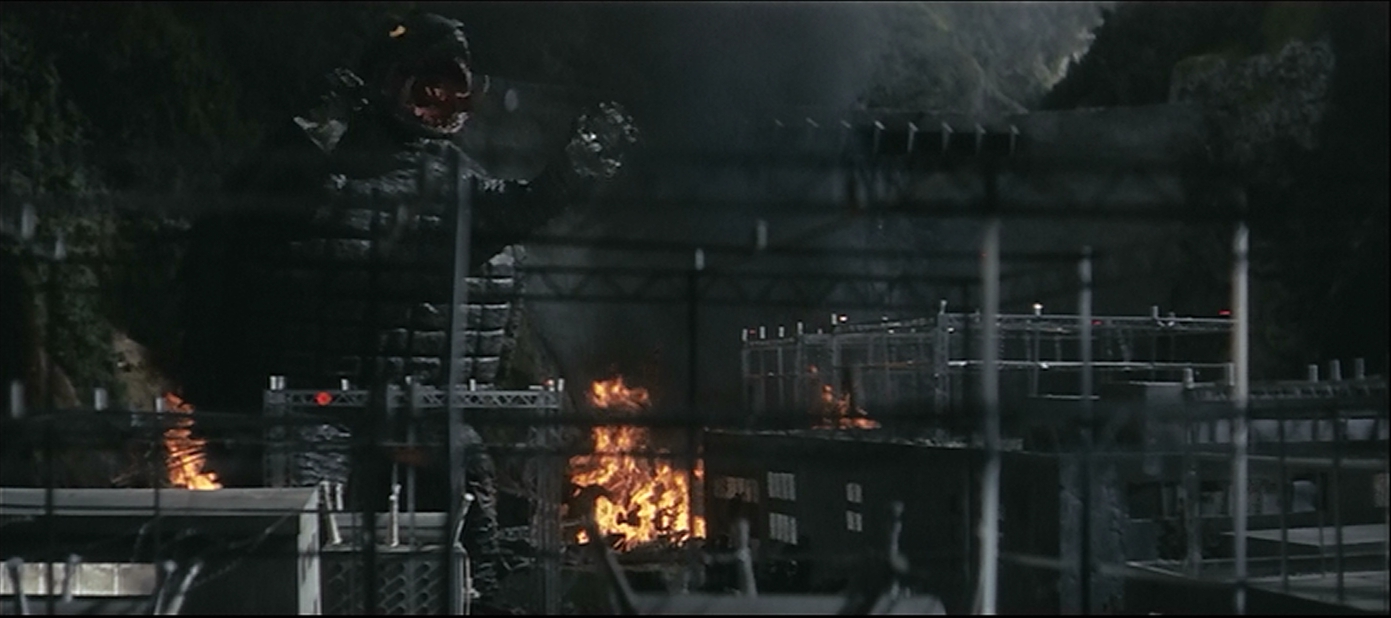

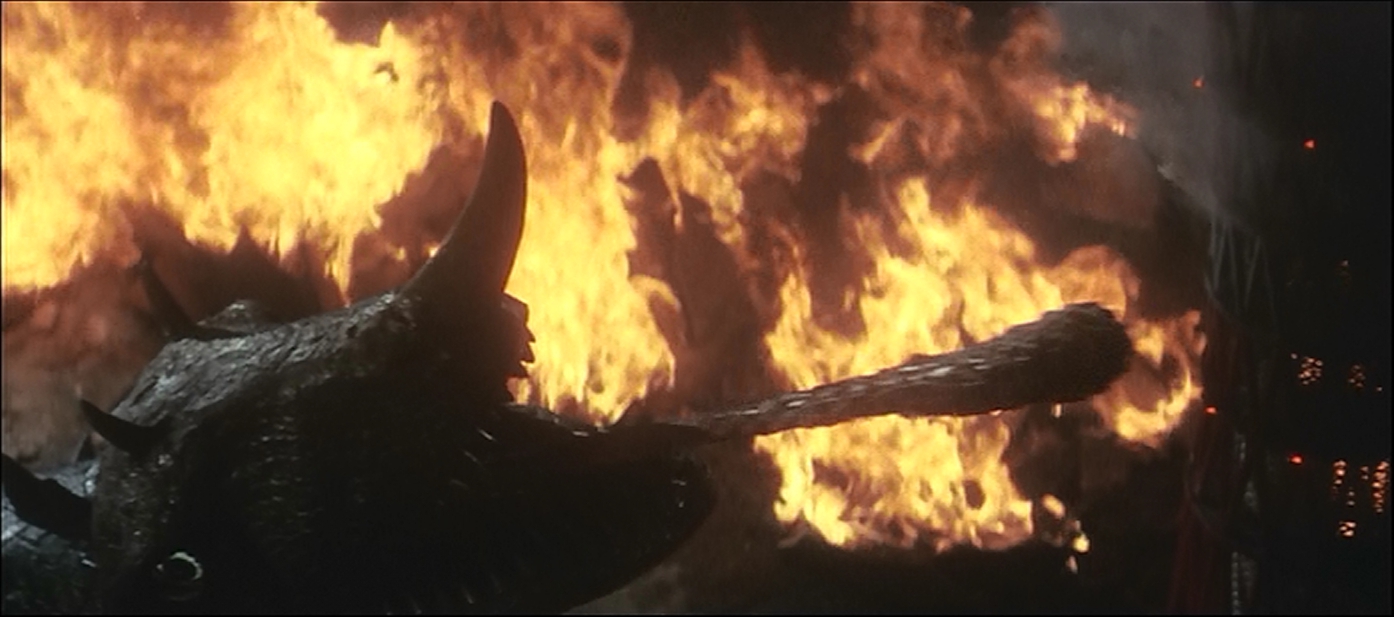

Barugon takes a number of attributes from the chameleon, including the forward horns and long tongue. It's screetchy roar is distinctive but lacks menace. The suit design is interesting, boasting such achievements as light-up eyes and spines and sideways-closing eyelids. But because Barugon is played by a man in a suit while being a quadruped, the majority of the shots are not full-length, which reveal that Barugon goes on hands and crouched back legs. The most effective showing of Barugon is from the front, and I think the director was aware of this. In keeping with Gamera destroying a landmark, Barugon stomps through Kobe, pausing to smack the Kobe Port Tower with it's long tongue until it falls.

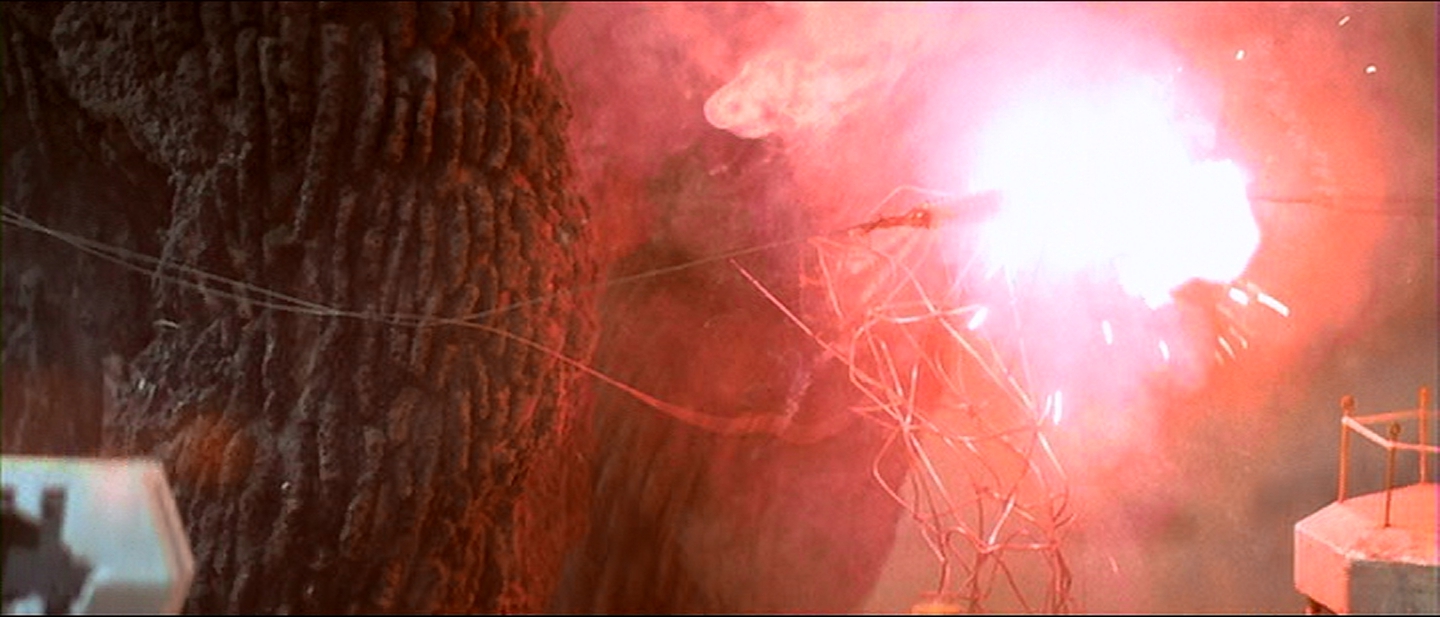

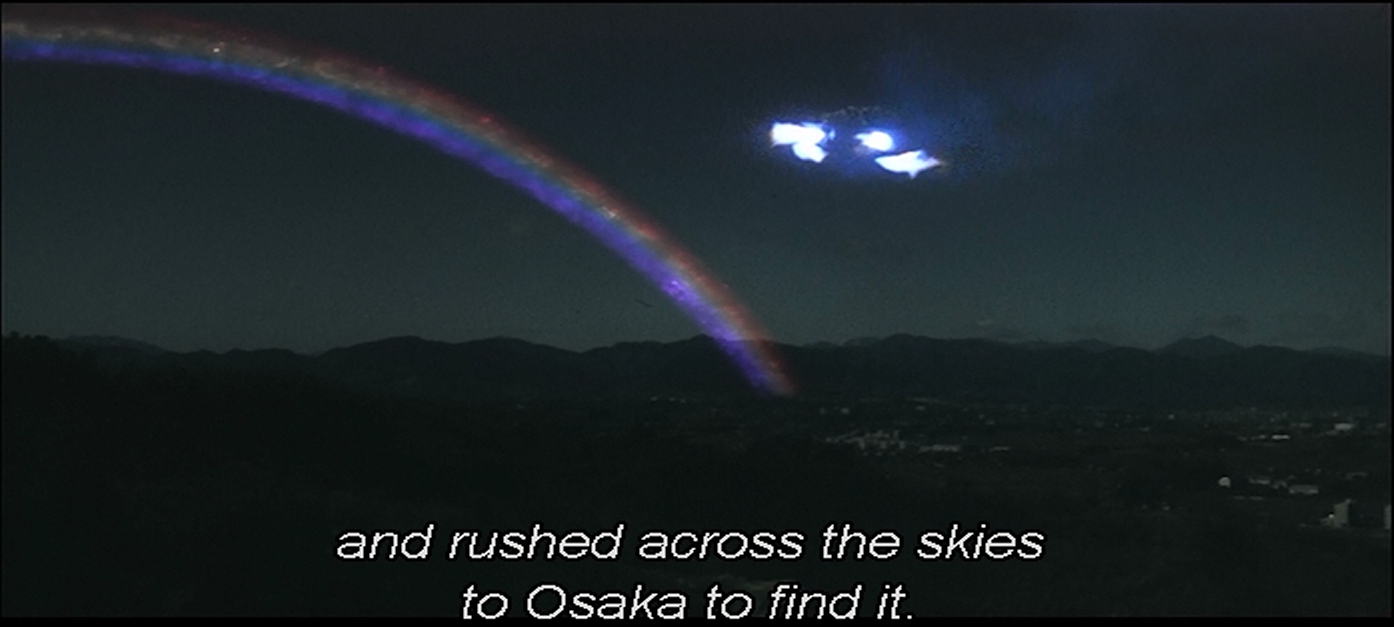

Later, rampaging through Osaka, Barugon reveals that it can project a freezing vapor out of its tongue, and the city becomes encased in ice and snow as it passes. He freezes Osaka Castle, last seen (and destroyed) in Godzilla Raids Again. When the Japanese decide to strike at him from long distance using missiles, Barugon pre-emptively retaliates with a destructive rainbow that comes out of his back horns. While it's lovely to see his deploy a new power, since the more powers he's got, the more powerful Gamera will have to be to defeat him, I wonder how he knew about the missiles. How close were they during deployment?

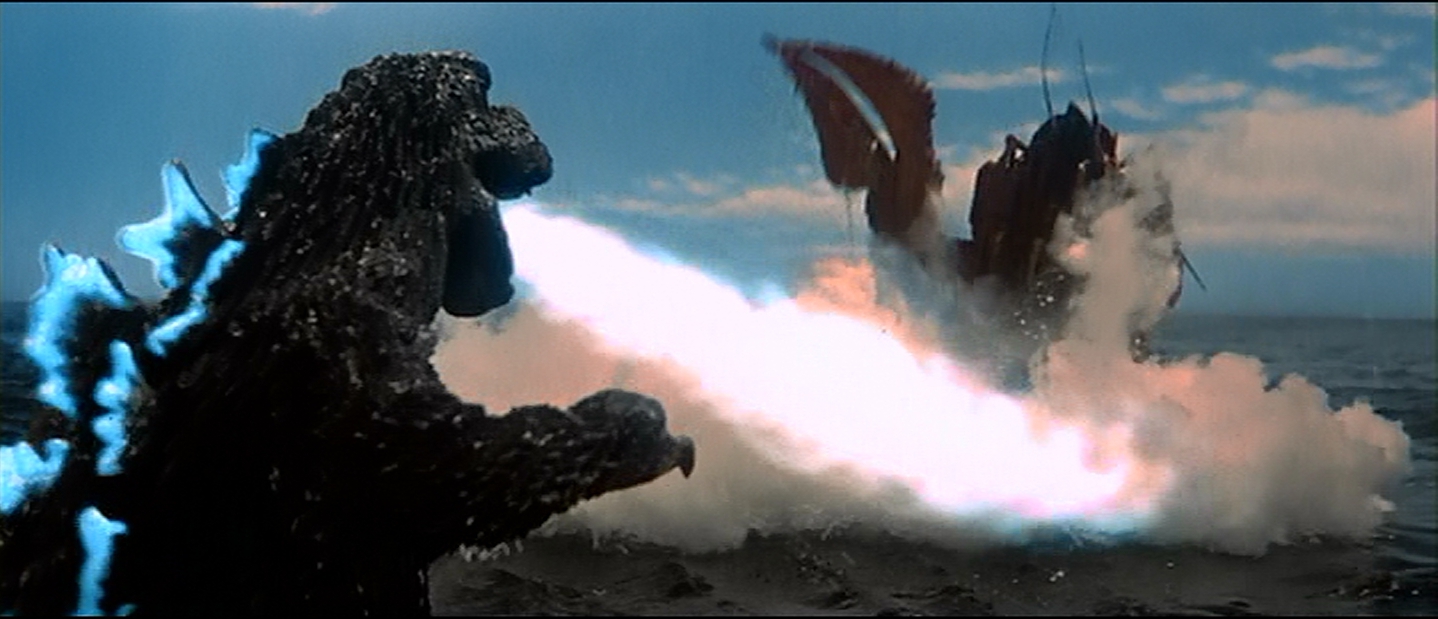

Setting off the rainbow lures Gamera to Barugon, since Gamera is constantly looking for more energy to devour. And then the fight is on.

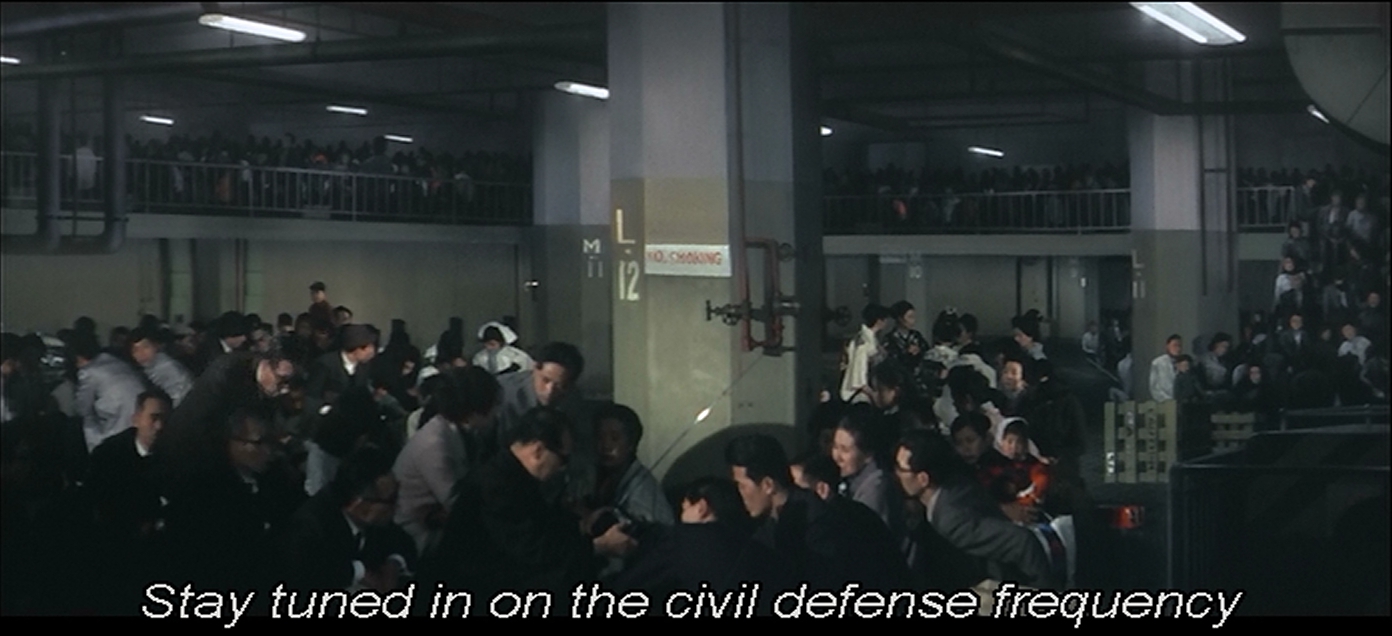

One major difference between this film and all other Gamera films is that we do get scenes of people huddled in subway stations. So the film conveys a sense that the giant monsters aren't just stomping on buildings, they're also rampaging across peoples' lives. We have a number of shots that humanize the destruction, but the sequence is brief.

In the middle of the film, for Gamera and Barugon's first fight, Gamera crashes into the former headquarters of the Japanese 4th Army, which could be a reiteration of the common theme that the military is useless. We have seen jets and tanks be ineffectual against Barugon. On the other hand, it could just be a large building close to Osaka Castle for Gamera to crash into.

One of the differences between Toho's Godzilla team and Daiei's is the weight of the costume. Toho created a series of linked sections for Godzilla's tail, so the tail doesn't bag like a piece of cloth. I wasn't aware of the craftsmanship until I watched this film. Barugon's tail and legs don't stretch like skin, and show a tendency to pucker where they attach to the torso.

In a change from the Godzilla formula, Gamera loses his first round to Barugon. Barugon's ice vapor overcomes Gamera's fire, and after a brief fight, Gamera is frozen. But we know Gamera is the franchise's darling, so he'll be back.

The end of the film is rather abrupt. Once it is determined that Barugon can be killed by water, Gamera, who apparently knows this, drags Barugon into the water and its freezing breath and rainbow beam do it no good. It's not so much a fight as Gamera showing up, dusting the monster, and the flying off.

The ending makes the film feel rather empty to me. I love many giant monster films that aren't Godzilla, but the Gamera films have so little below the surface. They aren't trying to mean anything, they are just trying to entertain. I find little complexity to them.

The commentary on the Shout Factory disk is pure pleasure. Jason Varney and August Ragone are very informative and speak of a lot of facts and interesting details, but it's very strange to realize that Jason Varney watched the same four o'clock films I did, on the same Connecticut channel, WVIT, broadcasting out of Farmington.

Next week, we returen to Toho, and my first viewing of the highly respected War of the Gargantuas, sequel to Frankestein vs Barugon.